Édouard Vuillard belonged to a generation of artists and writers who were fascinated with the domestic interior: a space that hummed with psychological undertones, private thoughts and intimate relationships.

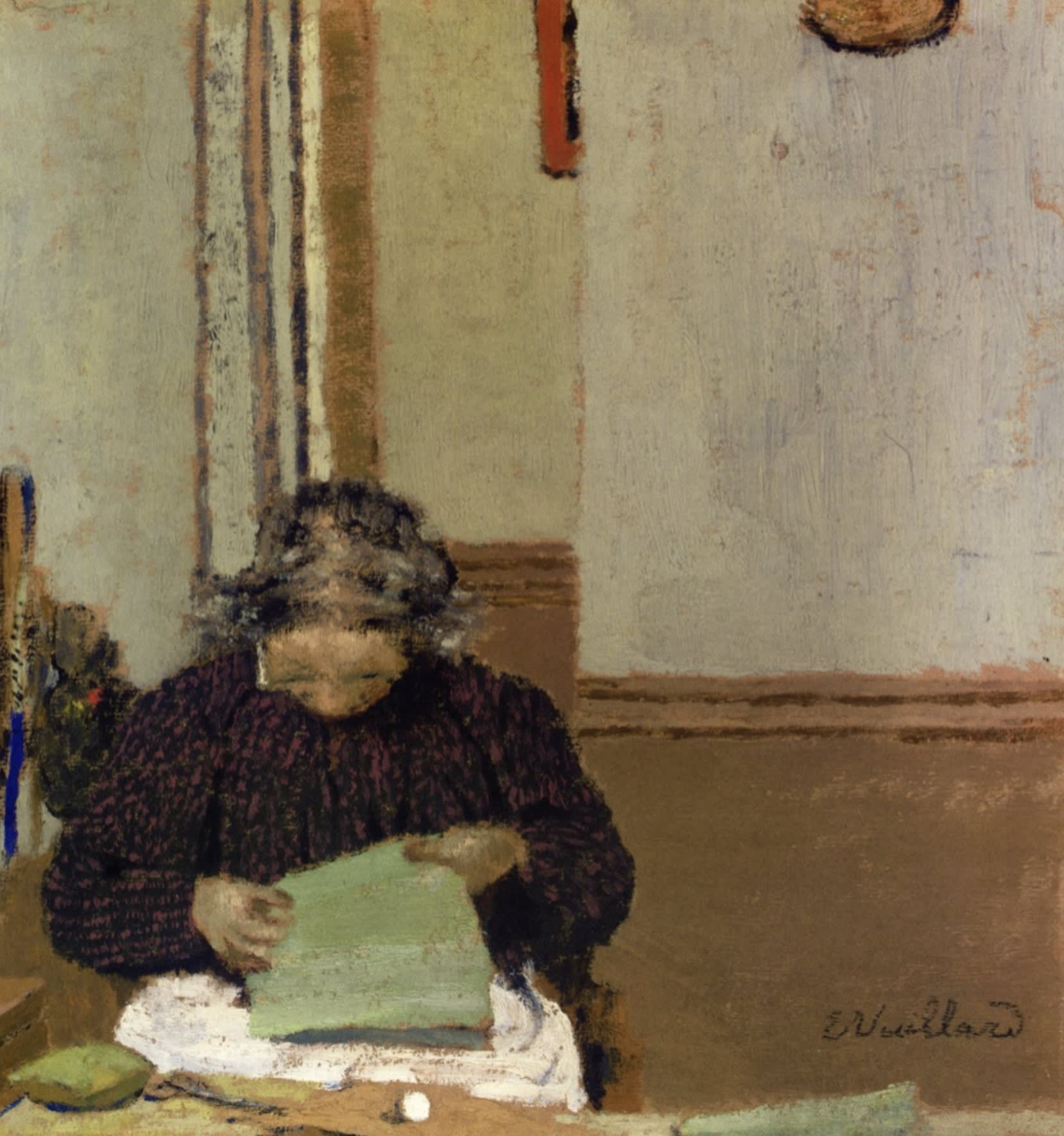

When the ‘painters of modern life’ emerged on the French art scene in the 1860s and ‘70s, their art contained much that was new but also much that was familiar. Though they rejected morality in art along with ancient clothing and renaissance furniture, they retained story-telling and long-held conventions of genre (the distinction between a landscape and a portrait, for instance). Though Édouard Vuillard (1869-1940) came half a generation after the likes of Renoir, Monet and Degas, his interests were largely in keeping: he wanted real people, not ideals. His work presents modern-day dress and interiors in a mode of genre painting as lively and intimate as any since seventeenth-century Holland.

Late nineteenth-century France and the early modern Netherlands shared a bourgeois feeling for plush fabrics – a preference that, in fin-de-siècle France, was especially prominent in the Vuillard household. Passing comparisons between Vuillard and Vermeer have often proved irresistible to critics, and a work like The Lacemaker – presumably familiar to Vuillard, who visited the Louvre regularly from the age of seventeen – has a tantalising affinity with the French artist’s paintings of his mother the dressmaker at work.

Vuillard belonged to a wave of French writers and painters who believed in the importance of interior spaces: bedrooms, drawing rooms, the kitchen, a greenhouse, the shabby parlour, a fragrant breakfast room with fresh-cut dahlias on the table. Such places had a sensory appeal, especially for Vuillard the period’s gaudy wallpaper and upholstered furniture, which translated into sumptuous flat patterns in painting. More than this, the enclosed domestic space was a human environment, macerated with psychological undertones, private thoughts and intimate relationships. A painting like Marcelle Aron seated in the greenhouse at Ormesson is not merely a painting of a woman seated in a greenhouse: she is part of the interior space, filling it, even as the patterns and her apparel consume her.

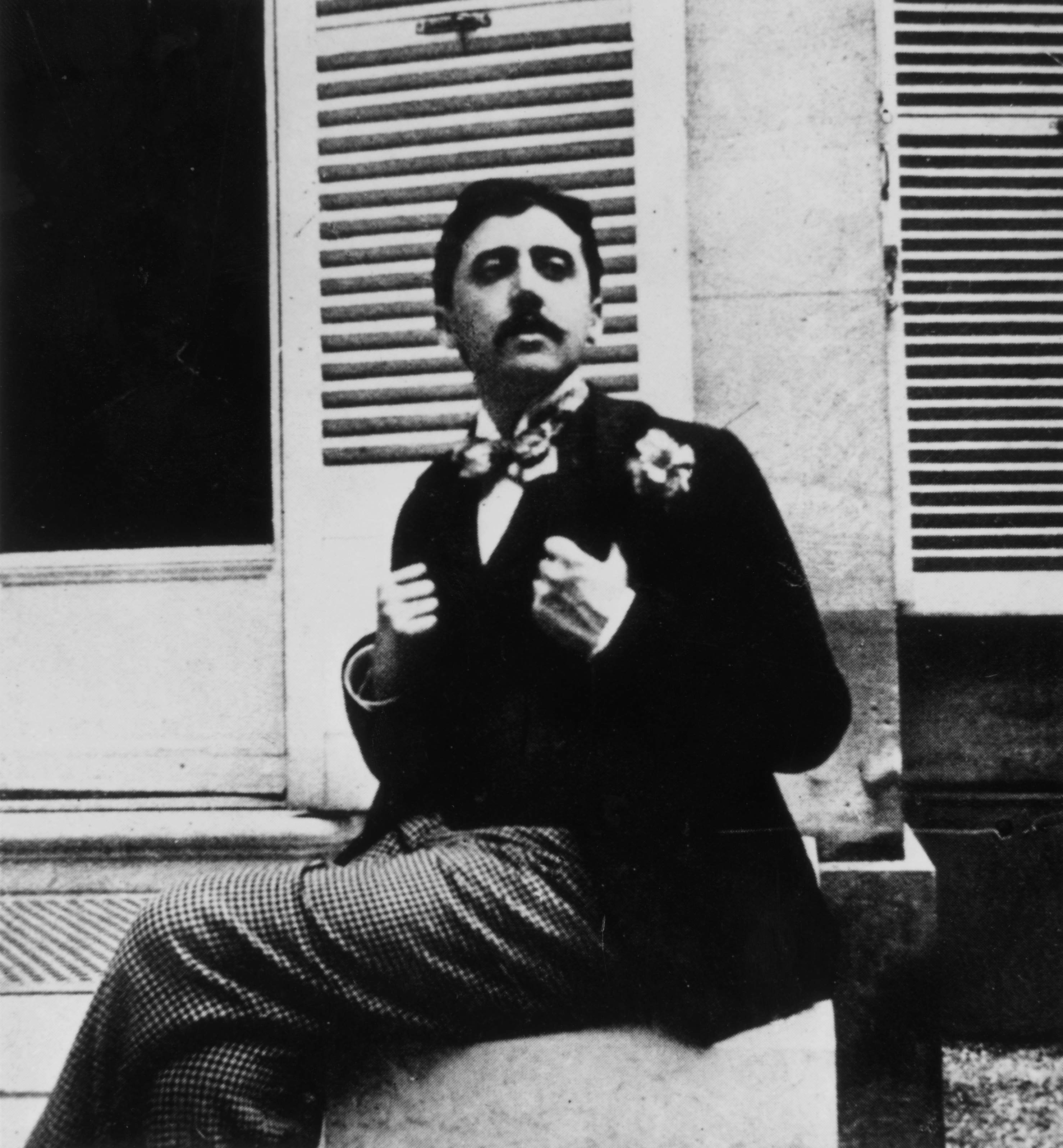

Another Parisian concerned in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries with interior spaces was the writer and hypochondriac Marcel Proust, an acquaintance of Vuillard’s. Like the protagonist in his epic novel À la recherche du temps perdu (‘In Search of Lost Time’), Proust was often confined indoors by illnesses both real and imagined (his asthma was severe though some of his other complaints were delusional). So much time spent in rooms gave an intensity to domestic descriptions in his writing. The Captive begins with a heightened, sensory account of the street outside pervading his apartment, the interior space seeming to encompass the whole world beyond. The description gives a good sense of how expansive the inner rooms of Vuillard’s paintings could be.

At daybreak, my face still turned to the wall, and before I had seen above the big window-curtains what shade of colour the first streaks of light assumed, I could already tell what the weather was like. The first sounds from the street had told me, according to whether they came to my ears deadened and distorted by moisture of the atmosphere or quivering like arrows in the resonant, empty expanses of a spacious, frosty, pure morning; as soon as I heard the rumble of the first tramcar, I could tell whether it was sodden with rain or setting forth into the blue. […] It was, in fact, principally from my bedroom that I took in the life of the outer world during this period.

The eponymous sitter in Marcelle Aron seated in the greenhouse at Ormesson was a cousin of Vuillard’s mistress, Lucy Hessel. Aron appeared in a number of Vuillard’s paintings. In 1897, he began experimenting with amateur snapshot photography, and the fleeting smile on Aron’s face in this painting suggests the kind of passing moment that he sometimes collected with the camera. Stripes and smudges of white-green light push through the steel armature of the greenhouse behind where Aron is seated. This particular hue of green is notably used in other artists’ work – Sickert, Michael Andrews and Peter Doig, for example – and almost always betokens the use of photographs. It has a distinctive, off-key blurriness and a resulting flatness which speaks of the photographic source. Whether or not Vuillard was assisted by photography in this work is of little consequence, however. Its more essential features come from the artist’s salient stylistic traits: delicate tone, a lack of underpainting and the patterned arrangement of colour.

1902, oil on board, 38 x 57 cm