InSight considers the distinctive appeal of pastel to artists ranging from Chardin to Walter Sickert, whose exhibition at Piano Nobile closes this Friday.

InSight No. 182

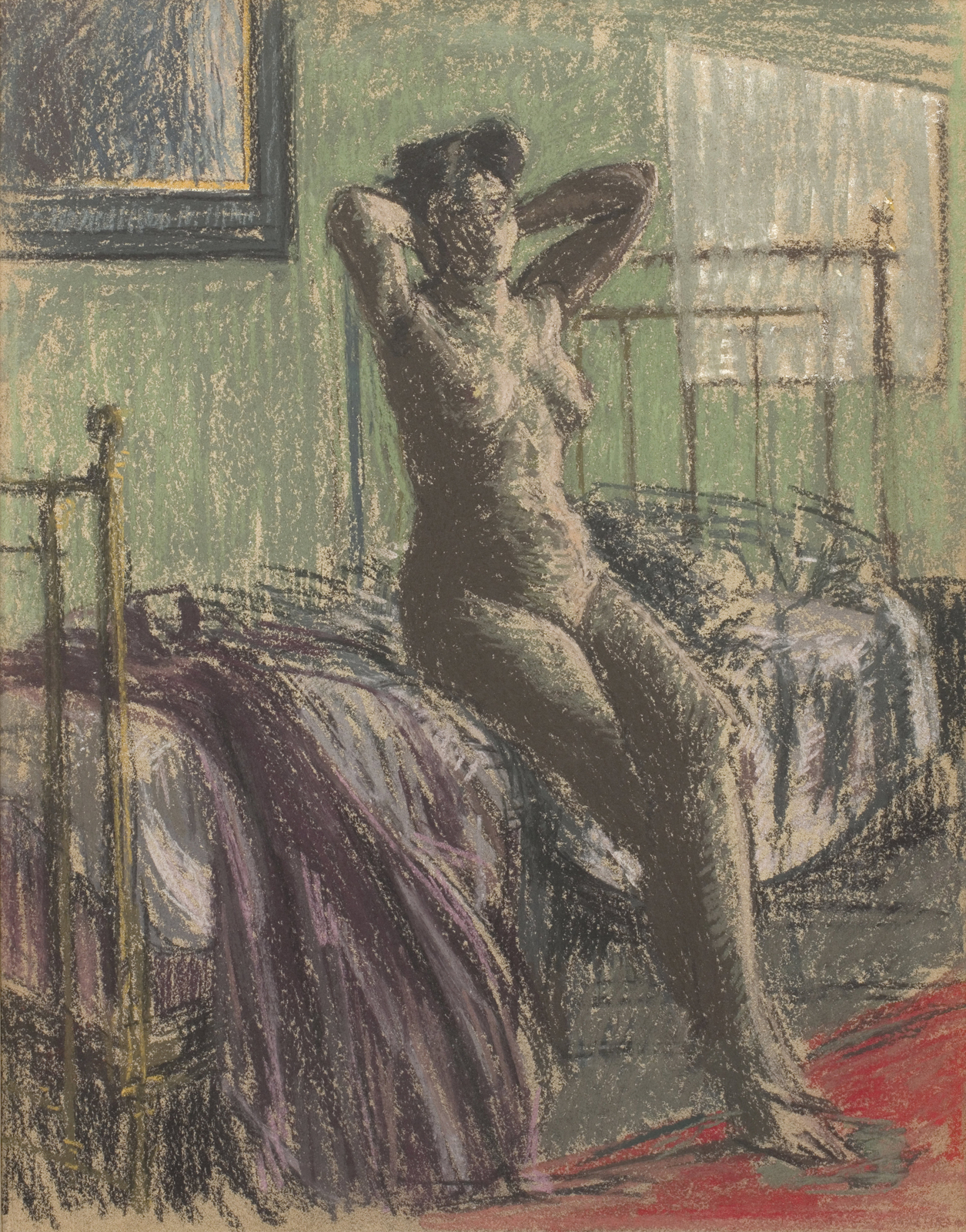

Walter Sickert, Réveil, 1905/06

Pastel is a stick or cake of powdered pigment bound together loosely with a binding agent such as gum. Following the established styles of coloured chalk and gouache, it has often been used similarly to these close neighbours, but in eighteenth-century France the likes of Jean-Baptiste Perroneau and Maurice Quentin de la Tour achieved distinctive pictorial effects using pastel especially in their head-and-shoulder portraits. Two late self portraits by Chardin are exemplary of this mode. The friable medium was variously rubbed smooth and laid on with linear hatching, and the result was modelling of convincingly life-like solidity. The saturated colour of pastel, which results from the absence of a medium, helped to create the elegant glow and brilliant highlights so prized by the ancien régime.

Pastel bears similarities to both painting and drawing, and different artists have harnessed it for a variety of purposes. It has often been used in mixed media works on paper especially for tinting charcoal or chalk drawings. This was the end to which James McNeill Whistler applied pastel in drawings of Venice he made in 1880. It can produce clean lines like a pencil and is applied dry, meaning that the colour does not change, and it cannot be mixed on a palette to produce new colours. Yet pastel delivers a similar intensity of colour to oil paint, and depending on the quality of the binding agent it can be smeared and evenly spread.

Notwithstanding the remarkable treatment of pastel made by his countrymen Eugène Delacroix and Jean-Francois Millet earlier in the nineteenth century, Edgar Degas made a sustained and personal treatment of the medium that demonstrated its hitherto unexplored range. Yet Degas admired the pastels of his forbears. He owned at least one example by Delacroix, which now belongs to the British Museum (see image below).

In Delacroix’s sunsets, the naturalistic treatment of his subject was married with the exquisite selection and combination of heightened colours, and this also became a foundational aspect of Degas’s pastels. Even as they were motivated by the accurate and poignant depiction of their subject—ballerinas stretching, a dance class, a woman ironing clothes or combing her hair—they rendered it in jarring, often exaggerated and unnaturalistic hues of colour.

Walter Sickert (1860–1942) described his friend Degas as ‘the lighthouse of my existence’, and from him he heard that ‘dans la peinture à l'huile il faut procéder comme avec le pastel’—in oil painting you must proceed as with pastel. ‘He meant’, Sickert later explained, ‘by the juxtaposition of pastes considered in their opacity.’ Considering his friendship with Degas, it is unsurprising that he himself used pastel for a time. Part of the attraction was its immediacy by contrast with oil painting, which required layers and drying time between sessions of work. As Sickert wrote when describing Degas’s preference for the medium, ‘A pastel is always ready to be gone on with.’ He had previously used pastel to tint works on paper depicting Venetian architecture. But shortly before he returned to London in 1905, Sickert made his first picture in pastel alone. He made several more over the next two years or so. Several were shown in his exhibitions at Bernheim Jeune in Paris in 1907 and 1909. Réveil was included in both, and it is currently displayed in Piano Nobile’s exhibition of the Herbert and Ann Lucas Collection.

Despite his knowledge of Degas’s pastels, Sickert did not imitate his friend’s handling of the medium. In a work such as Degas’s Deux danseuses au repos, refulgent colours are layered in a tight web of striated applications. By comparison Réveil was also executed with finely entangled streaks of colour, but the web is much looser and the underlayers or ground are exposed (a pastel technique sometimes called ‘scruffing’). A wider selection of colours produces a much greater contrast of light and shadow than Degas’s picture. This was partly a requirement of Sickert’s subject: a naked woman stirring in the light of dawn, which enters through a window somewhere to the right of the brass bedstead. There are deep shadows at her back, while her legs, arm and torso are modelled in hues of yellow ochre, dark pink, warm grey and olive green. These colours are applied in finely scribbled lines, and their weight and volume differ from the broad, flat applications of pastel used to treat the back wall and tangled bed clothes in the foreground.

Besides Réveil, La Coiffeur and other female nudes depicted in domestic settings, Sickert also used pastel for a formal portrait of Mrs Robert Campbell (Bristol Museum & Art Gallery) and a single music-hall subject (Whitworth Art Gallery). Where the bedroom pastels were apparently made from life, and there are few related preparatory works, the music-hall singer was composed with the assistance of drawings (some bear inscriptions that identify her as Amber Ansta). After thoroughly searching the medium, Sickert never returned to pastel. He had exhausted his interest in it. ‘Each time he met one of his friends’, wrote Robert Emmons, ‘he was trying out a new method: a new ground, a new medium or a new varnish.’ Although Sickert’s experiments principally concerned oil paint, for a short time he adopted pastel as a suitable vehicle for the message he had to convey: a tale of sorry lives lived in exquisite twilight. He moved on, but the results he achieved in Réveil and other pictures equalled his contemporaneous successes in oil paint.

Images:

Jean-Siméon Chardin, Self Portrait with Eyeshade, 1775, pastel on paper, 46 x 38 cm, Musée du Louvre, Paris

James McNeill Whistler, Venetian Canal, 1880, black chalk and pastel on paper, 30.1 x 20.5 cm, Frick Collection, New York

Eugène Delacroix, Study of the sky at sunset, n.d., pastel on blue paper, 22.8 x 26.8 cm, British Museum, London

Edgar Degas, Deux danseuses au repos, c. 1898, pastel on paper, 92 x 103 cm, Musée d'Orsay, Paris

Walter Sickert, La Coiffure, 1905/06, pastel on paper, 71 x 55 cm, Private Collection

Walter Sickert, La Comedienne, c. 1906, pastel on paper, 60.5 x 47.2 cm, Whitworth Art Gallery, University of Manchester

Walter Sickert, Réveil