An unbroken line connects Lynette Yiadom-Boakye’s invented figures to paintings made in the early Renaissance and after.

InSight No. 181

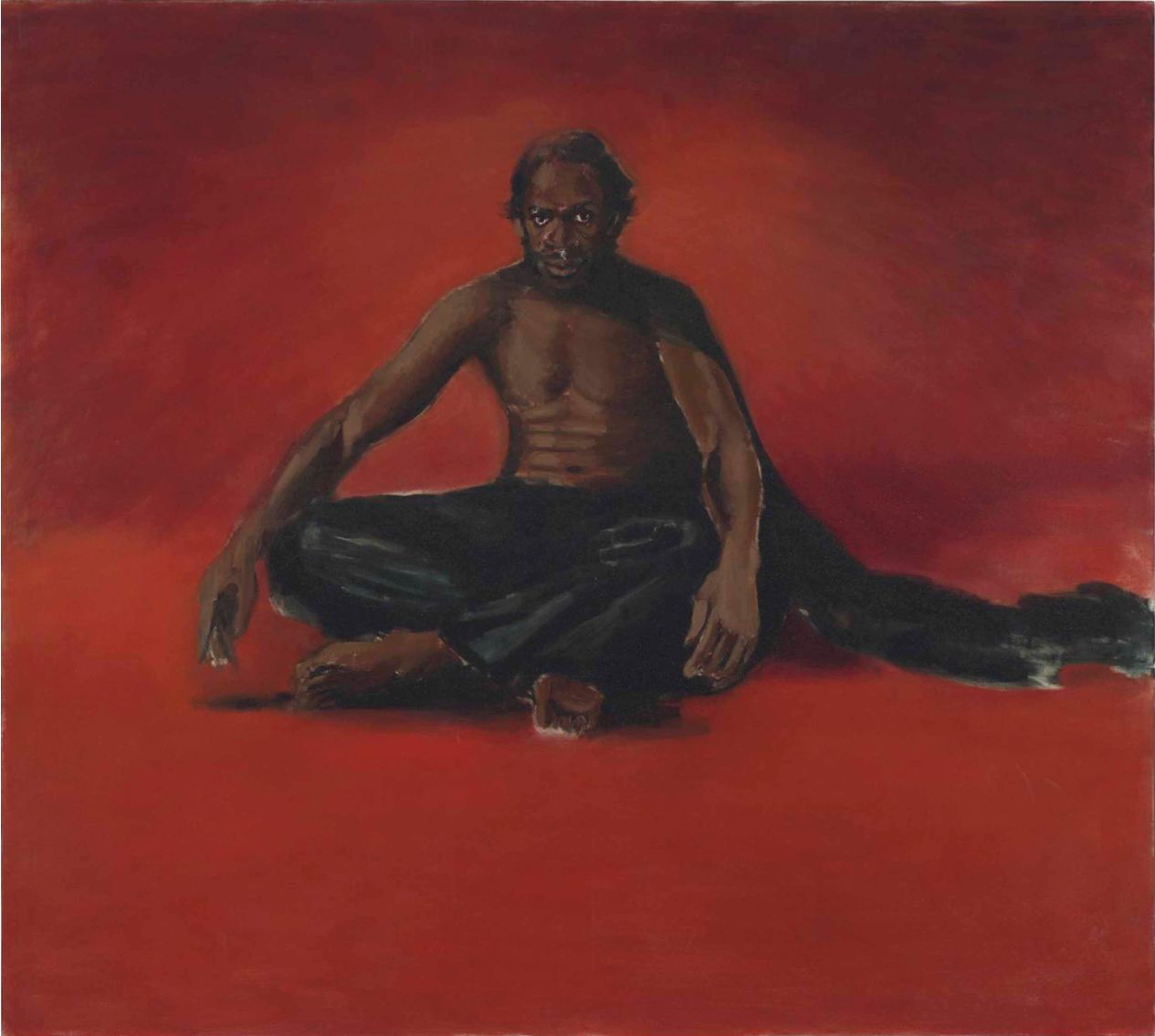

Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, Rose Nether Poetry, 2012

Not all paintings of the human figure are based on life study. Artists have long understood that the authority of their figures did not necessarily depend upon likeness to a specific individual. In his celebrated book Painting and Experience in Fifteenth-century Italy, the art historian Michael Baxandall suggested that the faces of saints and the holy family in altarpieces were sometimes intentionally generalised. This allegedly encouraged devotees to develop their own idea of these holy faces and thereby create a more intense, personal form of devotion. In other cases such as Piero della Francesca’s painting of the Archangel St Michael, figures that adhered to a type—golden curls, boyish features—nevertheless possessed distinctive features and a compelling sense of personality.

The fifteenth-century Italian polymath Leon Battista Alberti cautioned against invention over study. In his treatise De Pictura, he wrote that painters with ‘no model before them to follow [...] simply fall into bad habits of painting’. By contrast he praised those painters who were true to life, and he emphasised ‘the power and attraction of something taken from Nature’. Despite this judgement, concrete examples show that the differences between real and invented faces are seldom obvious. The convention of donor portraits in altarpieces—accurate portrayals of the people who paid—illustrates the ambiguity around likeness. Although the figures of Christ, the Virgin Mary or St Thomas may not have been studied from life, their human presence and animation is often undeniable. They hold their own beside the likes of Chancellor Rolin and Tommaso Portinari.

Only the most prodigal artists are able to compose the figure convincingly without some life model or source. The sketches of Raphael provide one example. A sheet in the British Museum contains the airy wonderings of his mind as he ranged across a variety of possible physical relationships between the mother and child. Much as a novelist composes a sentence—the placement of adverbs, the order of clauses, the rhythmic emphasis—so too must figure painters organise the bodies that they represent. An inexhaustible range of positions allows for endless combination and recombination. The turn of a head, the articulation of hands or the arc of shoulders can be varied and reimagined until a fitting solution—telling, persuasive, evocative—can be settled upon.

As centuries passed and manners changed, painters discovered new regions of informality. In the hands of Rembrandt and Rubens the human figure came closer than ever to the pathos of reality. In the following century Jean-Honoré Fragonard’s ‘fantasy figures’ explored the limits of uninhibited painterly invention, which facilitated gestures and attitudes that were unprecedented in their liveliness and naturalism. Whether they depicted real or imagined individuals, as was questioned by the National Gallery of Art’s exhibition in 2017, Fragonard’s fantasy figures have the unmistakeable immediacy of a human subject. They mediate the realms of human imagination through the inventive, bravura handling of oil paint.

More recently the subject of fantasy figures has been adopted by the British painter and writer Lynette Yiadom-Boakye (b. 1977). The characterisation of her figures is richly developed with facial expressions and attitudes suggestive of specific bodies studied from life. But her method is rather to invent figures by combining visual sources, which she accrues for the purpose of making her paintings. Speaking of her work, she told Antwaun Sargent for Interview Magazine in 2017: ‘Everything’s a composite. I work from sources. I make scrapbooks, I make drawings, and collect things that I might use later, so they are all very literal compositions in the way that I pull things together.’

In Yiadom-Boakye’s painting Rose Nether Poetry, the figure is larger than life. Like all others in the artist’s work it is consciously shorn of contemporary features that might one day cause the painting to age prematurely. (She has previously remarked that for this reason she does not paint shoes; her figures either wear socks or bare feet.) Yiadom-Boakye is also a writer of verse and prose fiction, and her exhibitions and paintings bear literary titles such as To Improvise A Mountain and No Patience To Speak Of. Her titles seldom deliver an obvious description or interpretation of the images to which they pertain. But the elusive relationship between title and image reflects the private, uncommunicable creative zone from which Yiadom-Boakye’s paintings emerge. Like Piero’s St Michael or Fragonard’s figures de fantaisie, her people exist but not amongst flesh-and-blood mortals. They are paintings rich with the characteristics of ardent, engaged human beings.

Images:

Piero della Francesca, St Michael, 1469, oil on wood, 133 x 59.5 cm, National Gallery, London (detail)

Jan van Eyck, The Madonna of Chancellor Rolin, c. 1435, oil on panel, 66 x 62 cm, Musée du Louvre, Paris (detail)

Raphael, Study for a Virgin and Child, c. 1506–07, pen and ink on paper, 25.3 x 18.3 cm, British Museum, London

Jean-Honoré Fragonard, Young Woman, c. 1769, oil on canvas, 62.9 x 52.7 cm, Dulwich Picture Gallery, London

Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, No Patience To Speak Of, 2010, oil on canvas, 180.4 x 200 cm, Private Collection © The Artist

Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, Rose Nether Poetry, (detail)