To coincide with Piano Nobile’s current exhibition, InSight considers an important painting at the heart of Herbert and Ann Lucas’s Sickert collection.

InSght No. 177

Walter Sickert, Ennui, c. 1913–14

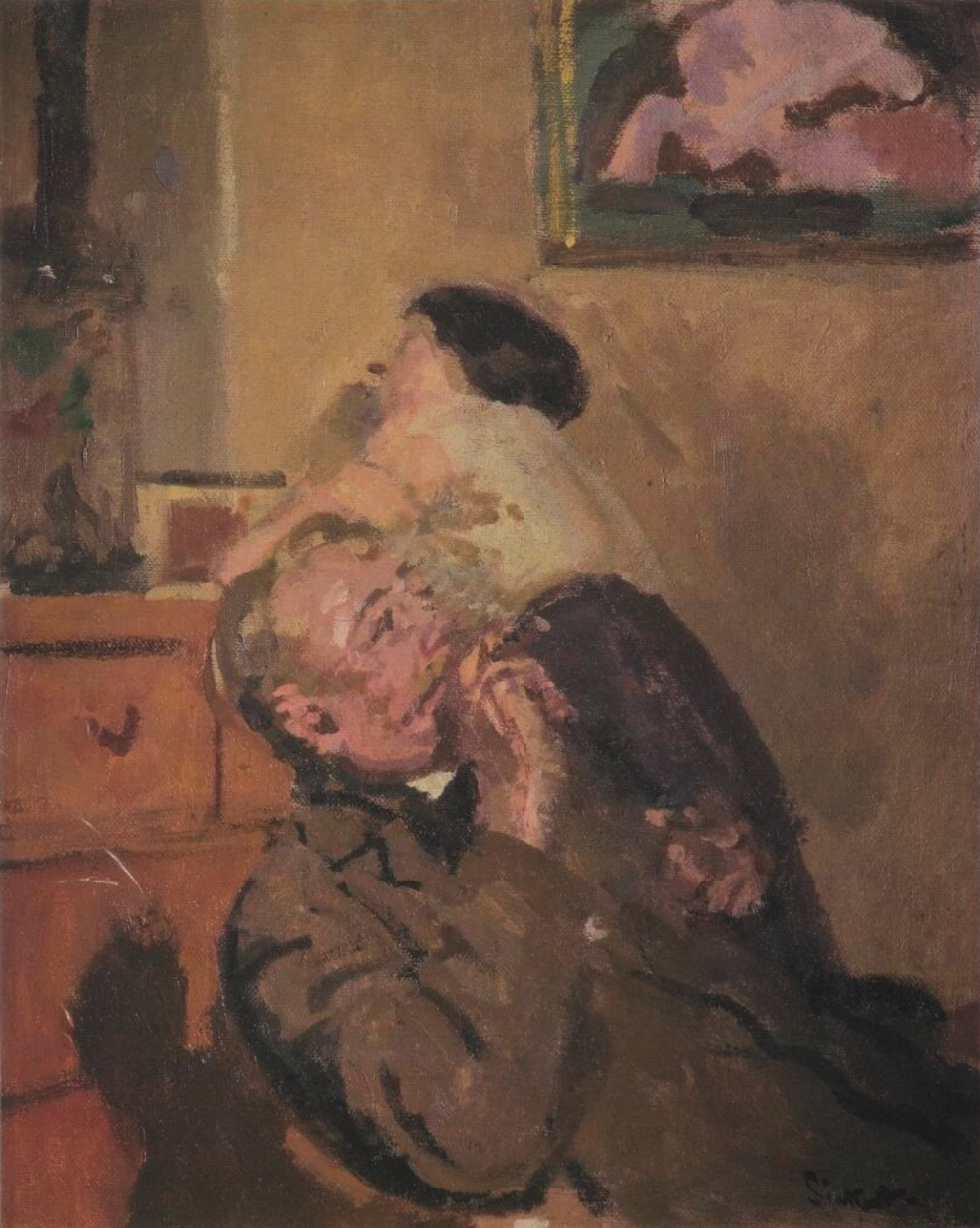

In Joris-Karl Huysmans’s novel À Rebours, published in 1884, it is said of the protagonist that quoit qu'il tentât, un immense ennui l'opprimait: ‘whatever he attempted, an immense ennui oppressed him’. Ennui was the keynote of much French modernist literature, and Walter Sickert’s (1860–1942) composition of that title memorably illuminates the theme. Like savoir faire or naïveté,‘ennui’ is a French loan word of untranslatable depths. Its meaning is inseparable from its form. Sickert had an ear for languages; he spoke English, French, German and Italian, and acquired the dialects of Venice and Le Pollet in Dieppe with apparent ease. The titles of his paintings—variously English, French, Italian, Latin—often communicate a meaning by innuendo or synecdoche. Ennui is characteristically freeform in yoking a numinous concept to the humdrum immediacy of its subject-matter. A man is seated, chewing the remains of a cigar, gazing into the void; this is Hubby, as he was known, who worked for Sickert as a model and assistant. A woman behind him leans against a chest of drawers, her manner abstracted; this is Marie Hayes, the artist’s charlady. ‘It is all over with them, one feels’, Virginia Woolf wrote in 1934.

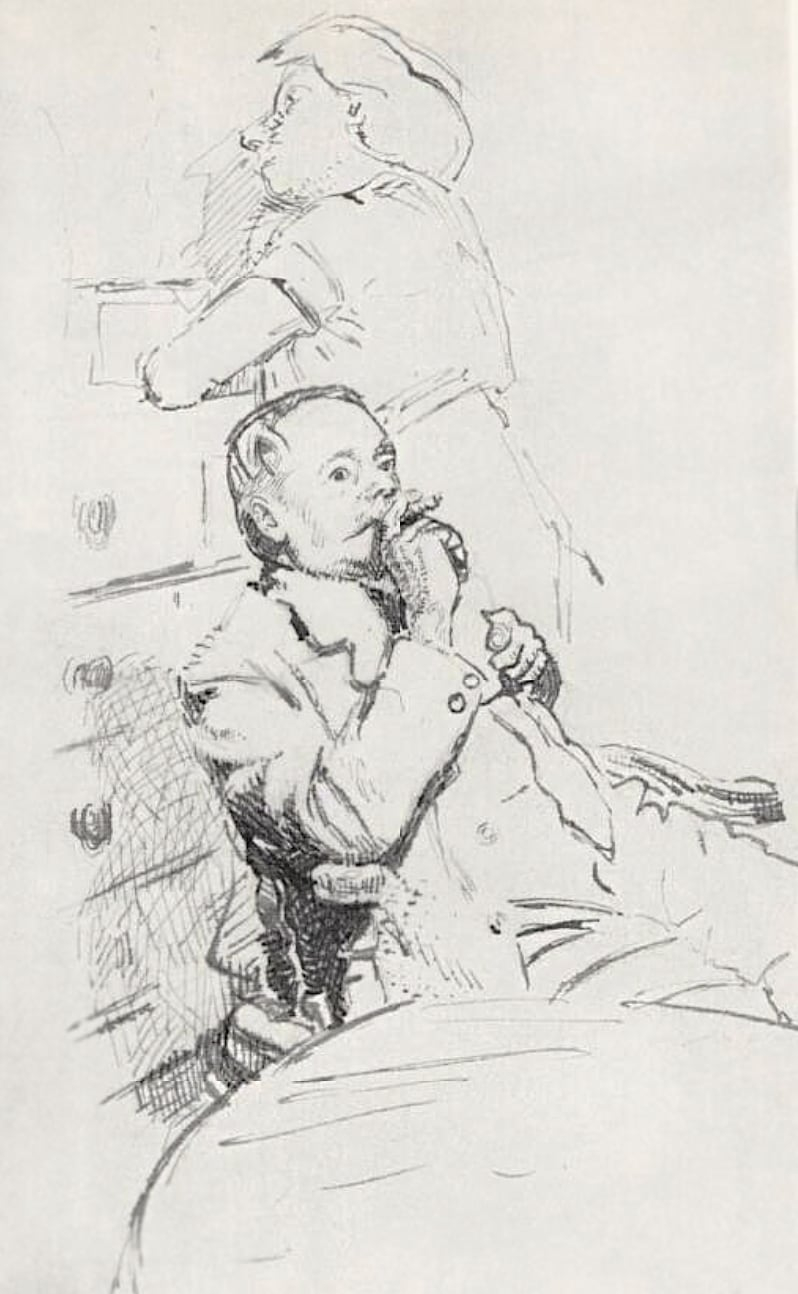

With craftsman-like intent, Sickert often repeated his compositions with the fluency of an ironmonger forging nails or a carpenter joining furniture. (With characteristic verbal dexterity, he was fond of claiming that the Greek word for ‘artist’ meant ‘joiner’.) His techniques included tracing, squaring up and cropping. By these means he replicated, enlarged and recast his subjects. From approximately 1910, his saleable pictures were often produced from material found in his drawings. The invention of his life drawings involved both the preparation of a subject—renting a furnished interior and peopling it with models, for instance—and then finding sufficiently lively graphic notation to describe it. Sickert proceeded to use these life drawings, treating them as ‘documents’ and sometimes extrapolating from their contents more than once for the purpose of further drawings, paintings and occasionally etchings.

Sickert painted a large number of two-figure conversation pieces in the years leading up to 1914, in which year he exhibited the largest and most complete painting of Ennui(Tate). The study required to make these conversation pieces produced in him a powerful, even directorial sense of control over the nuances of figure composition. Subtle adjustments in the attitude or facial expression of two figures could significantly alter the meaning of their interaction. An amicable conversation or amorous tête-à-tête might become an interrogation or ill-tempered dispute.

Even when the mood went unchanged, Sickert’s repetitions of a subject were always handled differently. As such they are seldom simulacra of an ‘original’, but rather inventive reiterations of an established composition. In the different versions of Ennui—five paintings, at least fourteen drawings, three finished etchings—the treatment of Hubby’s face, for instance, makes him variously tired, grandiloquent, frog-like and (in the version owned by the Ashmolean Museum) positively geriatric.

The large-scale painting of Ennui required considerable preparation since Sickert was little accustomed to working larger than the scale of vision. One aspect of preparation was life drawing: Wendy Baron has catalogued fourteen related drawings, of which eight are studies of local details. Three paintings, including the Lucas collection version, were likely made as part of Sickert’s enthusiastic exploration of the subject prior to painting the large version. Each one crops the composition differently. The largest of these smaller paintings was acquired by HM The Queen Mother before 1941 and is now owned by her grandson HM King Charles III. It omits the table and the mantelpiece, and Hubby leans further back than in other versions. The Lucas collection painting, in which Hubby is more upright, includes the glass on the table but omits the mantelpiece and crops out the head of his female companion. The smallest painting, owned by a private collection, omits the table and mantelpiece but includes the picture on the wall and the bell jar filled with stuffed birds. Another painting (Ashmolean Museum), a half-size version of the largest, was likely made sometime later between 1916 and 1918. This painting is in a higher key and its style differs from the other paintings.

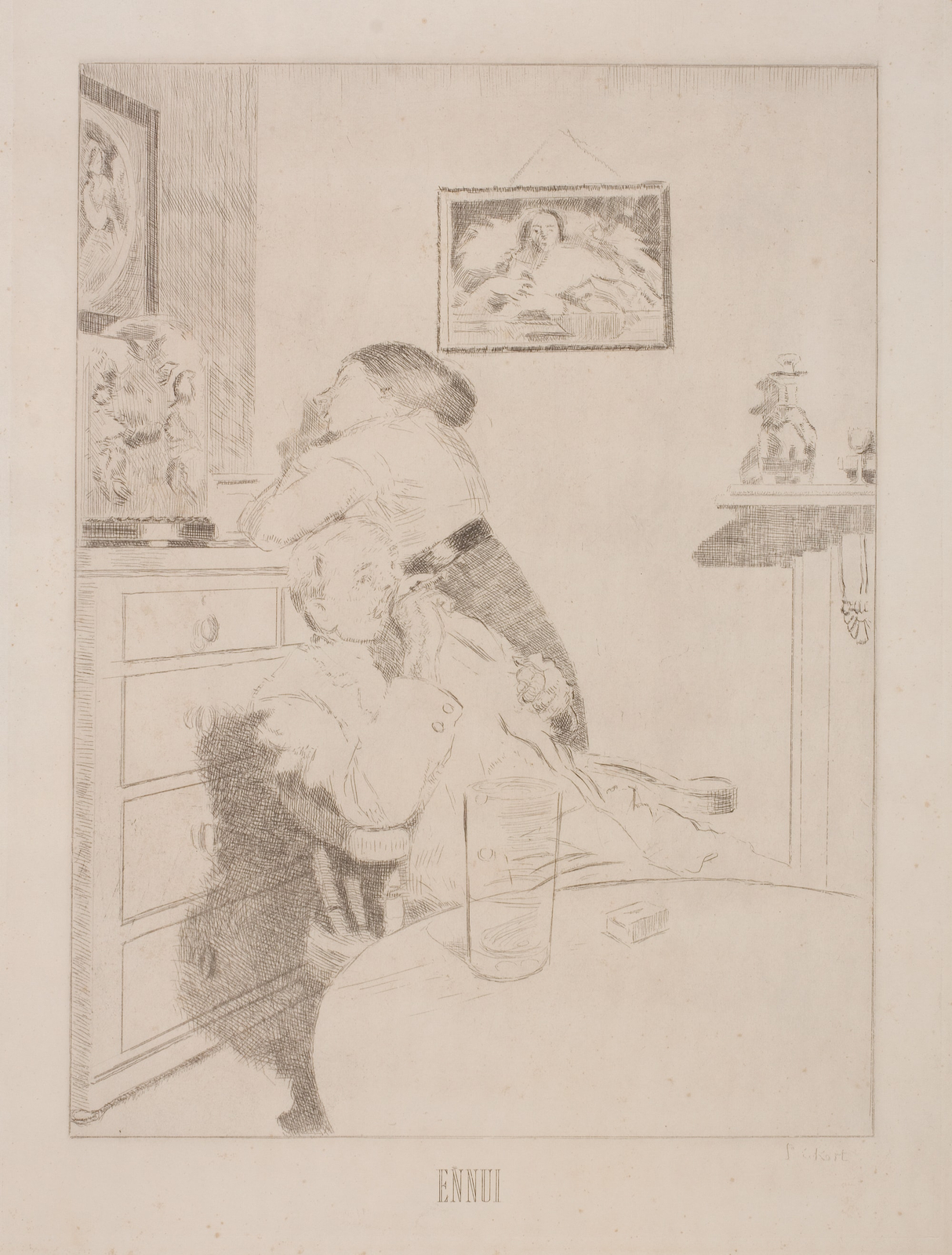

Sickert’s repetitions were not limited to paintings and drawings, and many of his etchings reiterate the subjects of his paintings. This was the case with Ennui. His large-scale painting of Ennui was first shown at the New English Art Club in summer 1914, and following the warm reception it received, Sickert conceived three etchings—large, medium and small—of which the largest was published by his dealers the Carfax Gallery in 1915. Sickert had started making ‘large’ etching plates around 1910, and typically treated them as lightly worked preparatory sketches for smaller, closely studied etchings. But in the case of Ennui, he selected the large plate for publication: the medium plate wasn’t published and sold until the twenties when the Leicester Galleries worked with Sickert to print some of his earlier plates; the small plate, never published, yielded only a handful of proof impressions.

Even as Sickert’s Ennui drew upon an important literary theme of his times, it has continued to attract the admiring gaze of subsequent generations of artists. In 1941, Ruskin Spear’s homage to Ennui collaged together Sickert’s composition alongside a war-damaged street dressed with a ‘Dig for Victory’ poster. Similarly to Ennui, Frank Auerbach’s two large paintings of an interior in Vincent Terrace, Islington, painted in 1982–84, depict a table and an ambivalent encounter between the figures seated round it. More recently, Lynette Yiadom-Boakye has included four of Sickert’s preparatory drawings for Ennui in her exhibition To Improvise A Mountain, currently on display at Leeds Art Gallery before travelling to MK Gallery. They are hung in a cluster alongside photographs by the New York artist and AIDS activist David Wojnarowicz, and their presence in the exhibition—along with work by Bonnard, Vuillard and contemporary artists such as Lisa Brice and Jennifer Packer—illustrate the continuing relevance and fluidity of Sickert’s work.

Images:

Walter Sickert, Ennui, exh. summer 1914, oil on canvas, 152.4 x 112.4 cm, Tate, London

Walter Sickert, Study for ‘Ennui’, c. 1913–14, pencil, pen and ink on paper, 16 x 10 in, whereabouts unknown

Walter Sickert, Ennui (detail)

Walter Sickert, Ennui (The Large Plate), 1914, etching and engraving on laid paper, 45.1 x 32.9 cm (plate)

Walter Sickert, Ennui, c. 1913–14, oil on canvas, 50.8 x 40.6 cm, HM King Charles III

Installation photograph of To Improvise A Mountain: Lynette Yiadom-Boakye Curates at Leeds Art Gallery

Installation photograph of Sickert: Love, Death & Ennui at Piano Nobile, London