Paula Rego used pictures to tell stories. Sometimes they presented a version of her own life. Other times they illustrated fairytales or her own fantastic imaginings.

InSght No. 175

Paula Rego, Girl Exposing her Throat to a Dog, 1975

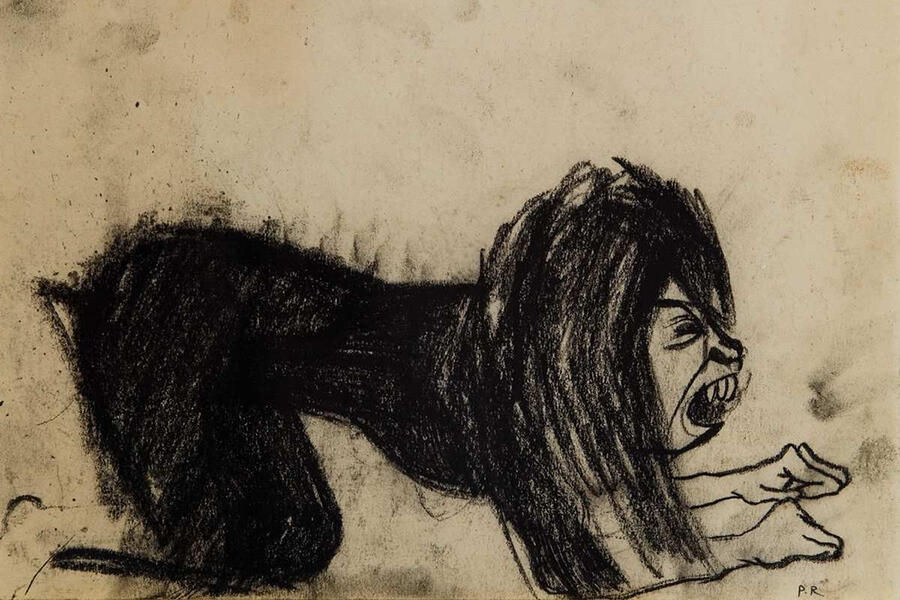

In 1988, Paula Rego’s (1935–2022) husband Victor Willing died. He had been diagnosed with multiple sclerosis twenty years earlier, but as he grew older their life together became increasingly difficult. Rego suffered with depression and underwent Jungian psychoanalysis. Even as she cared for him, Willing’s decline and the consequent demands produced a mixture of strong emotions. His reduced situation produced deep sadness and compassion, yet Rego’s sense of sympathy was flecked with anger and self-immolation. In the final years of Willing’s life, beginning in 1986, she articulated their personal circumstances in narrative images about a girl and a dog. The imagery developed a theme that began much earlier with the zoomorphic drawing of a ‘dog woman’, which Rego made as a student at the Slade School of Fine Art.

The girl and the dog are shadows of Rego and Willing, although these figures likely do not re-enact scenarios taken from real life. The content of these images unfolds in a realm disconnected, yet not entirely separate from the facts of life; like a fairytale they have their own internal logic. Speaking to Maya Jaggi in 2004, she explained the attraction of working at one remove from reality: ‘You can get away with so much more truth and cruelty if you dress people up as animals, but they're acting parts.’ In the ink drawing entitled Girl Exposing her Throat to a Dog, the young girl bears her neck and stoops to present it willingly in an act of self-sacrifice, while two figures—a woman and a child—stand to one side and observe. The relationship between the girl and dog is intimate but ambiguous. The scene unfolds before one’s eyes and the conclusion is uncertain.

At the time of Rego’s retrospective at Tate Britain in 2021, Laura Stamps compared the girl and dog series with Tableau vivant by the American painter Dorothea Tanning. In that strange and haunting picture, a dog—a Lhasa Apso of wildly engorged proportions—embraces a naked human figure. The dog turns to gaze upon the viewer. It is unclear if the limp figure is being attacked or supported by the animal. The personification of animals is a long-established feature of human life: it encompasses both the serpent in the Garden of Eden and the seemingly targeted disruption caused by urban foxes (‘they’ve been at the roses, again!’). In the hands of Tanning and Rego, animals were invested with greater faculties and—in the case of Tableau vivant—these are symbolised by an enhanced physical presence. Even as the dog in Rego’s work remains dog-sized, it has disproportionate psychological presence. Its relationship to the girl is not merely that of a pet to its owner, but rather such as exists between equal partners.

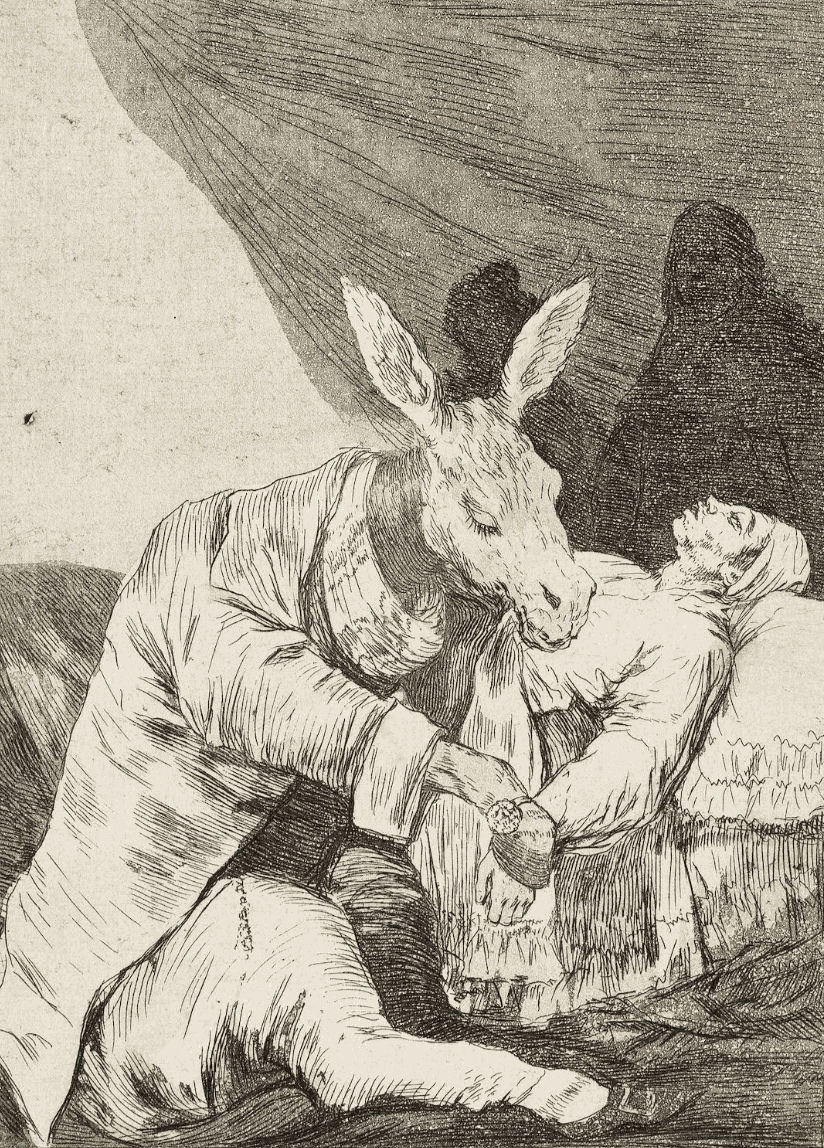

Long before Darwin revealed the evolutionary ancestry of man and showed him to be primes inter pares in the animal kingdom, animals were used to symbolise the imperfect or problematic aspects of humanity. In Goya’s series of prints called Los Caprichos, ‘the caprices’, animals frequently take the place of humans, while implying the debased nature of those they imitate. In ‘Si sabrá mas el discipulo?’ (‘Might not the pupil know more?’), a mature ass is teaching a colt. In ‘Ni mas ni menos’ (‘Neither more nor less’), a monkey is painting the portrait of an ass. In ‘De que mal morira?’ (‘Of what ill will he die?’), the figure of a doctor—an ass dressed in human clothes—is doing more harm than good to his patient. Besides evident stylistic similarities between Goya’s graphic work and Rego’s drawings and prints, these two artists shared a deep sense of pessimism about human nature, which was expressed most clearly in their anthropomorphic treatment of animals.

In 1987, Rego’s dealer Edward Totah held an exhibition of her ‘Girl and Dog’ pictures. Amongst the works on display was a painting of a girl shaving a dog. He rests his front paws on her knee, while she holds his snout in the air and scrapes a coat-throat razor under his chin. In another work, Snare (British Council Collection), the relationship between the girl and the dog appears less amicable: he lies on his back while she holds his front paws and looks intently into his face. As in the work of Goya, anthropomorphised animals have often been used as substitutes for the worst of humanity. Yet in these works, Rego discovered poignant new territory in which the canine form barely conceals the human reality of the relationship. As with Pleasure Island in Pinocchio, where miscreant boys become donkeys, or the frog prince in the fairytale by the Brothers Grimm, Rego’s dog is bursting with bewitched human feeling. In the girl and dog series, Rego conjured profound and sometimes disturbing narratives that are irresolvably caught between the realms of fantasy and the immediacy of daily human cares.

Images:

Paula Rego, Dog Woman, 1952, Private Collection © The Estate of Paula Rego

Francisco José de Goya, ‘De que mal morira?’ [Of what ill will he die?] from Los Caprichos, 1799, Private Collection

Paula Rego, Untitled (Girl Shaving a Dog), 1986, Private Collection © The Estate of Paula Rego

Paula Rego, Girl Exposing her Throat to a Dog (framed)