To coincide with the Treasure House Fair and Piano Nobile’s online Viewing Room dedicated to new work by Grayson Perry, InSight considers the artist’s peculiar balance of the personal and impersonal.

InSight No. 174

Grayson Perry, A Tree in a Landscape, 2025

In the late nineteenth century, there was a craze for Velázquez. Many artists, Manet among them, made paintings that were both historicist and of the moment; backward looking, yet borne of communal, present-day interests. The infusion of historical and contemporary impulses has become an important aspect in much of Grayson Perry’s (b. 1960) work in recent years. In 2008, his large print Map of Nowhere grafted the medieval iconography of the mappa mundi onto the body of the artist, who appeared in the guise of a sixteenth-century Dürer-like figure. Then in 2012, his series of six tapestries called The Vanity of Small Differences cannibalised William Hogarth’s series A Rake’s Progress, and the blatant symbols of life in the early twenty-first century—mobile phones, Red Bull cans, The Futureheads—were used to garnish a tale of moral jeopardy no younger than the eighteenth century.

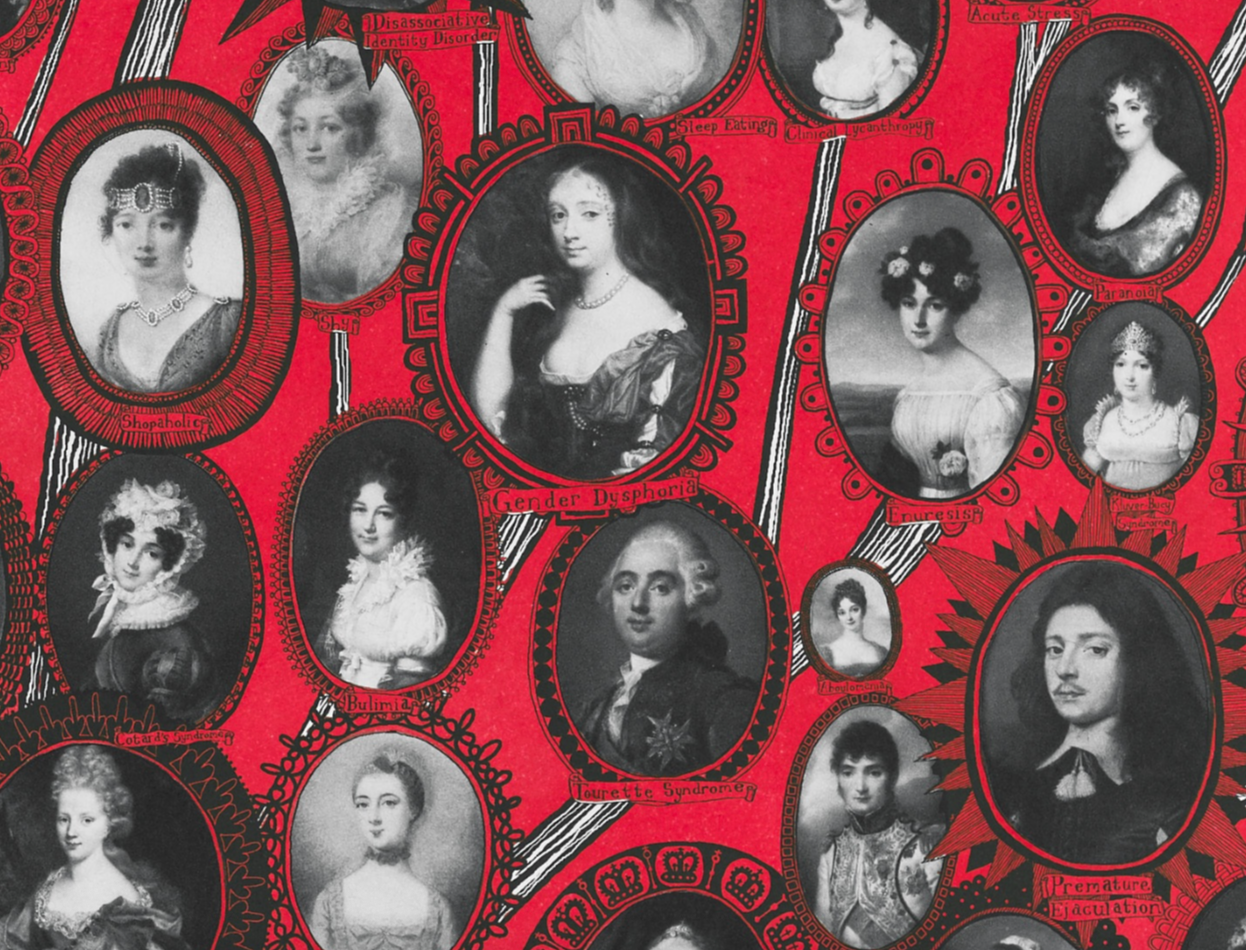

The imagery in Perry’s new print A Tree in a Landscape takes portrait miniatures from the Wallace Collection, London, and construes them as leaves on a (family) tree. As in much of his work a visual pun is in play, yet the pun is so intensely literal—it functions as an image rather than illustration—that the double entendre is continuously remaking itself and landing with renewed interest. The upper echelons of meaning in art—allegory, symbolism, metaphor—are of keen interest to Grayson Perry, whose choice of striking imagery is frequently motivated by grand narratives, sometimes about himself and his troubled existence ‘pre-therapy’, but more often about fictitious characters of his own invention. The protagonist of The Vanity of Small Differences was Tim Rakewell, for instance, while one subject of his current exhibition at the Wallace Collection, Delusions of Grandeur, is called Shirley Smith.

Shirley Smith is nursing a grievance. The Wallace Collection and its home—a mansion built for the Marquesses of Hertford—was her inheritance, or rather, it was that of her alter ego the Hon. Millicent Wallace, the ‘thwarted legitimate heiress’. The facts of Smith’s life are meagre: an Eastender, she was abused, spent some years in a psychiatric institution, discovered art and now, in a thinly veiled conceit, she makes work that bears a striking similarity to that of Grayson Perry. The family tree pictured in A Tree in a Landscape is layered with fiction and metafiction then. Its unifying theme, however, is mental health. Not so much a literal genealogy, the leaves of this tree constitute ‘a family tree of mental health diagnoses’.

Each portrait miniature reproduced on the map has a scroll, positioned similarly to a cartellino name plate, which seems to identify each individual by a mental health diagnosis. The plenitude of such vocabulary raises the spectre of overdiagnosis. Certain conditions—‘vanity’, ‘narcissism’, ‘perfectionism’—only rarely have cause to be considered through the lens of pathology. Others such as ‘caffeine withdrawal’ and ‘acute stress’ usually have a clear causal connection with external circumstances. But many of the diagnoses in Perry’s rubric have deep roots and complex symptoms. Amongst them are alcoholism and various addictions (to internet, pornography, gambling, cocaine). The regions of clinical psychosis—‘schizophrenia’—stand alongside those of severe neurosis—‘bipolar’, ‘dissociative amnesia’. Perry has always used words and vocabulary in concert with piquant imagery, and his encyclopaedic approach in works such as A Tree in a Landscape is an astute form of social commentary.

Notwithstanding Perry’s fascination with the contemporary pressures that condition our lives, his abiding topic is the human condition. The cataclysms of life are always present, and A Tree in a Landscape includes a swallow gliding above the terrain: this bird is called Loss. Much of his work is refracted through the prism of his own life experience, and autobiography has been a recurrent theme in Perry’s output. Whether through his alter ego Claire or the teddy bear Alan Measles, he has created a personal iconography and his work successfully enlivens form and content by handling both with a wilful, often joyous subjectivity. In A Tree in a Landscape, the face carved in the trunk is the artist’s own. By way of explanation, Perry remarks: ‘We all exhibit some traits that could be pathologised.’

Images:

Grayson Perry, The Agony in the Car Park, 2012, Arts Council Collection © The Artist

Laurence Hilliard, Thomas, Lord Coventry, after 1625, Wallace Collection, London

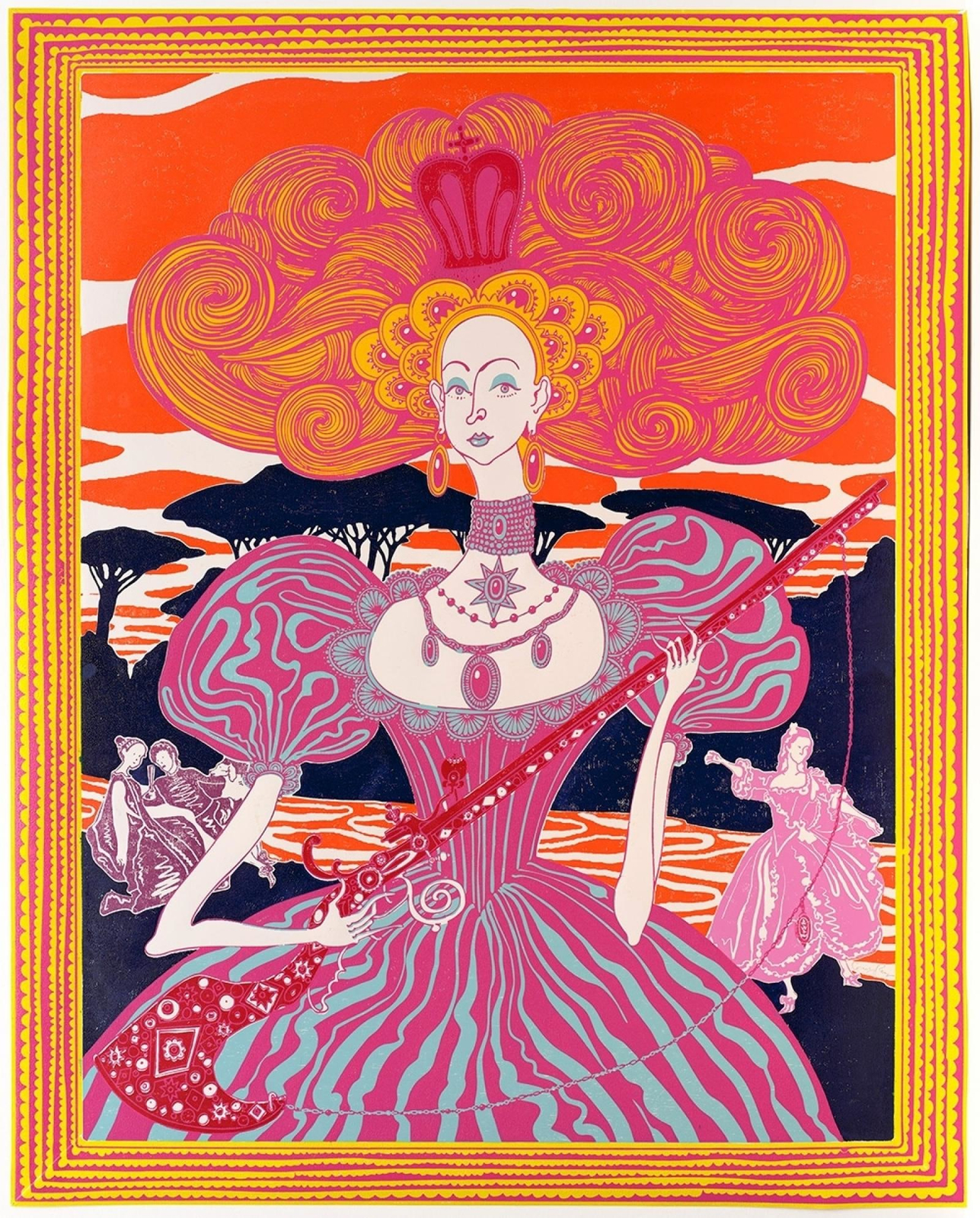

Grayson Perry, The Honourable Millicent Wallace (orange/pink), 2025, woodcut on paper, 149.5 x 119.5 cm (sheet),

edition 6 of 15

A Tree in a Landscape (detail)