‘I love Paris, why oh, why do I love Paris?’, sang Ella Fitzgerald. R. B. Kitaj loved it too. He lived there for a year between spring 1982 and April 1983, during which period he produced some of his finest scenographic drawings and prints.

InSight No. 172

R. B. Kitaj, Place de la Concorde, 1982–83

Almost immediately after he departed the city, R. B. Kitaj (1932–2007) came to mythologise ‘the year I lived in Paris’. It punctuated other periods of his life when he lived in London, New York, Spain and later Los Angeles, and it stood out as a peculiarly piquant and distinctive episode. He and his partner Sandra Fisher led a quiet, productive existence in ‘an ancient house’ at 61 rue Galande, a street in the Latin Quarter directly across the Seine from Notre Dame de Paris. Every day they saw their friends the Arikhas—Avigdor Arikha was a painter of international repute, like Kitaj represented by Marlborough Fine Art—and once a week Kitaj worked with the eminent printmaker Aldo Crommelynck, who had previously worked with Pablo Picasso and Kitaj’s close friend David Hockney amongst many others. Kitaj later recalled that it was ‘the happiest year of my life for a hundred crazy reasons. I felt hidden away in time and romance and I found or invented some of the lost Paris which people said was gone—the Paris of Henry Miller and René Clair.’ To him, it was ‘a dreamworld I stumbled into’, charged with erotic fantasies and veiled in the penumbra of literary history.

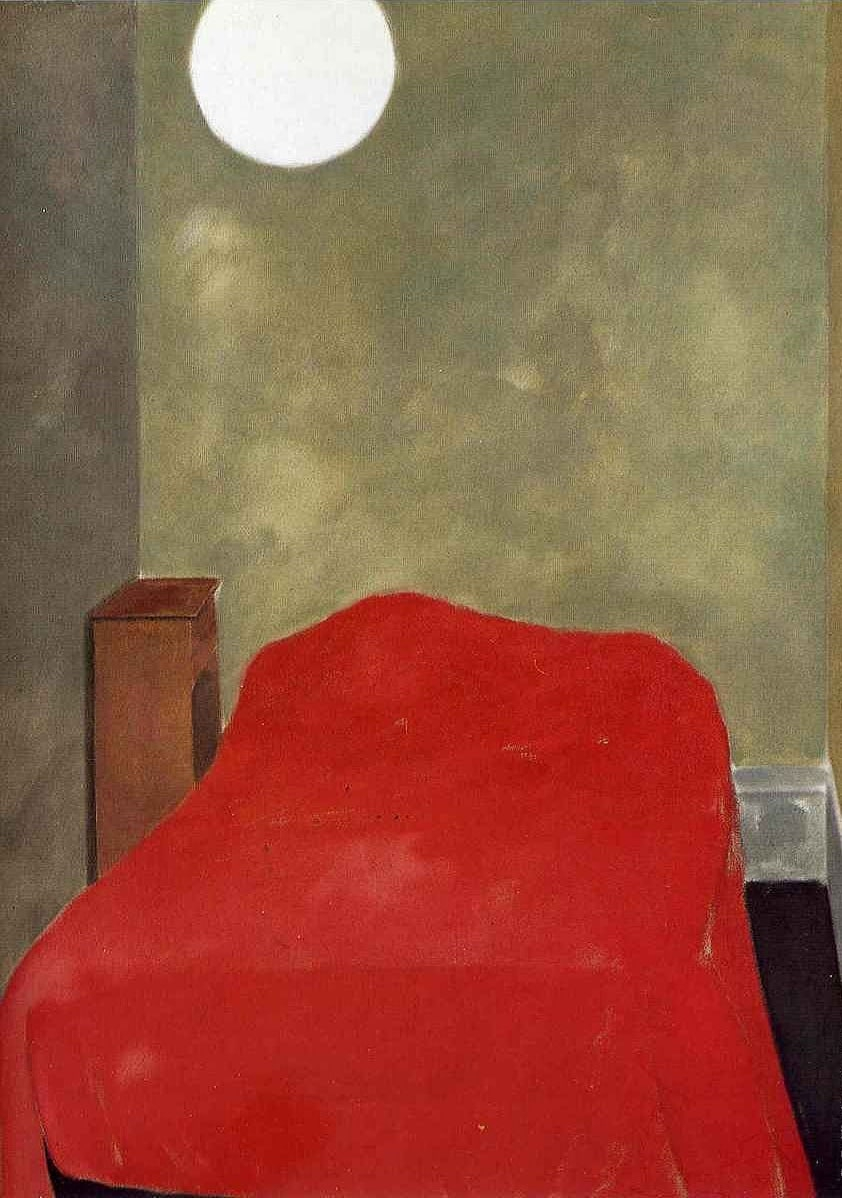

In his painting of a red-covered bed, The Room (Rue St Denis), which alluded to one of Paris’s most storied red-light districts, Kitaj created an empty space into which he could project his profuse imaginings—of sex, solitude, poignant encounters between strangers. His friend the art historian Marco Livingstone recorded that this image was ‘the memory of a prostitute’s bedroom’. In conversation with Kitaj, the writer Julián Ríos asked to retitle the picture ‘A Study in Scarlet’. Other works that Kitaj made in Paris included several self-portrait drawings, life drawings from the female nude (some called ‘American in Paris’), and a cycle of portrait drawings depicting his friend the poet Robert Duncan.

A child of the new world macerated in the literature and culture of the old, Kitaj was temperamentally drawn to what he called the ‘romance’ of European cities—Vienna, Barcelona and Paris especially. He once referred to ‘the romance of big city streets’, and as a teenager his idea of Europe was coloured by the films of Powell and Pressburger, especially The Red Shoes, which was set between London and Monte Carlo. Kitaj had a gift for living vicariously: a place was often alive to him with associations, as with the synagogue of Bevis Marks in London once attended by Disraeli in his boyhood, or the Grand Hotel in Oslo frequented by Ibsen. Paris also vibrated with associations. Some of these were visualised in one of his masterpieces, The Autumn of Central Paris (After Walter Benjamin), which evokes the café culture of Paris on the precipice of Nazi invasion in 1940. His notes for the painting referred to cafés as an ‘open-air interior (past which the life of the city moves along).’

The beauty of Paris was not wasted on Kitaj. Sometime during the winter of late 1982 and early 1983 he made a charcoal drawing using elements from Place de la Concorde, which was a twenty minutes’ walk away from rue Galande, the route of which led him through the Tuilleries. The sparce, frontal composition includes four discrete elements laid flat against the picture plane—a leafless tree, the statue de Brest, the Luxor obelisk spliced together with the Eiffel Tower, and one of the square’s grand, ornamental lamp posts. The imagery was too good to waste. In collaboration with the printmaker Crommelynck, Kitaj made a soft-ground etching based on the charcoal drawing which had perhaps been made with a print in mind.

The process of soft-ground etching involves a plate covered with a touch-sensitive ground. A sheet of paper is attached to the plate, and onto this the artist draws in reverse the image they wish to appear in the print. The artist’s positive markings will expose those areas of the plate meant to hold ink. After etching in an acid bath, the plate is washed clean; ink is applied; a print is pulled. Kitaj’s intermediary ‘transfer’ drawing of Place de la Concorde, which was attached to the etching plate, shown at the top and bottom of this InSight, was made in Crommelynck’s studio. Unlike the initial charcoal drawing and the subsequent print, this work is a mirror image of the composition. Kitaj added local areas of colour that enhance the atmospheric quality of the scene, at once emphasising the work’s autonomy from the monochrome print it helped to realise.

Images:

Rue Galande, Paris

R. B. Kitaj, The Room (Rue St Denis), 1982–83, Private Collection © R. B. Kitaj Estate / courtesy of Piano Nobile

R. B. Kitaj, The Autumn of Central Paris (After Walter Benjamin), 1972–73, Private Collection © R. B. Kitaj Estate / courtesy of Piano Nobile

R. B. Kitaj, Place de la Concorde, 1982–83, soft-ground etching on paper, 39.4 x 56 cm, edition 49 of 50

R. B. Kitaj, Place de la Concorde (framed)