This week InSight considers a canonical masterpiece by the youthful, effervescent artist Christopher Wood, which was painted near the end of his short life.

InSight No. 171

Christopher Wood, The Yellow Man, 1930

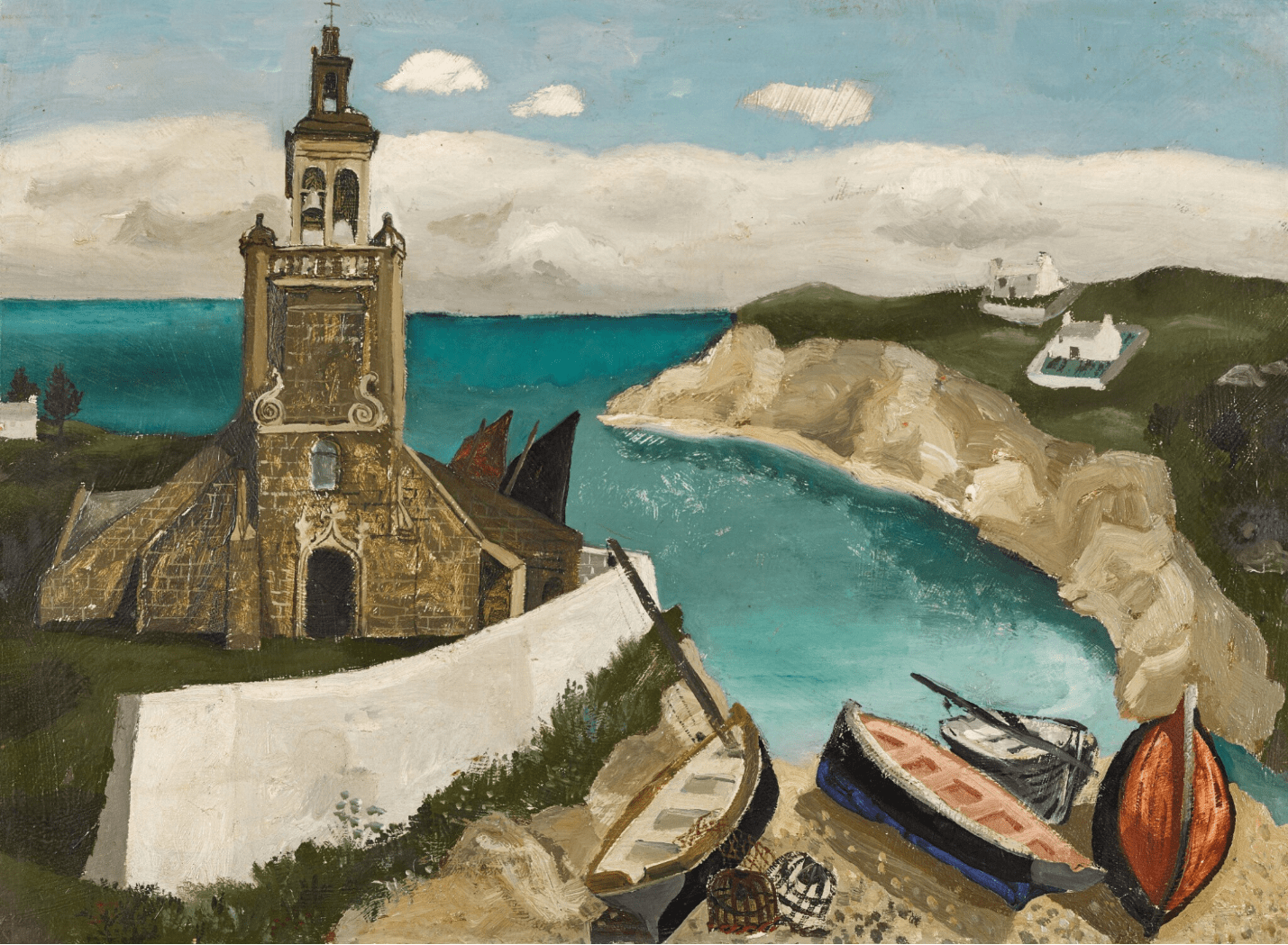

The last year of Christopher Wood’s (1901–1930) life was emotionally chaotic. The demands of an opium addiction and crippling professional uncertainty about his future as a painter were occasionally overwhelming. Yet during visits to Mousehole and St Ives in Cornwall and to Tréboul and Concarneau in Brittany, he worked with feverish intensity. He produced a significant corpus of nearly seventy paintings in the months leading up to his presumed suicide in August 1930. Wood’s painting had hitherto been dashing but eclectic, and he assimilated then shed a variety of different styles with great speed and facility. But the paintings he made from the summer of 1929 until his death are marked by a distinctive, homogeneous style: crisp, textured underpainting, usually produced with a ground layer of the glue-based material called Coverine; faux-naïf motifs (of boats, figures, churches), painted with simplicity and directness; and a poetic poignancy, variously banal, surreal, religious or erotic.

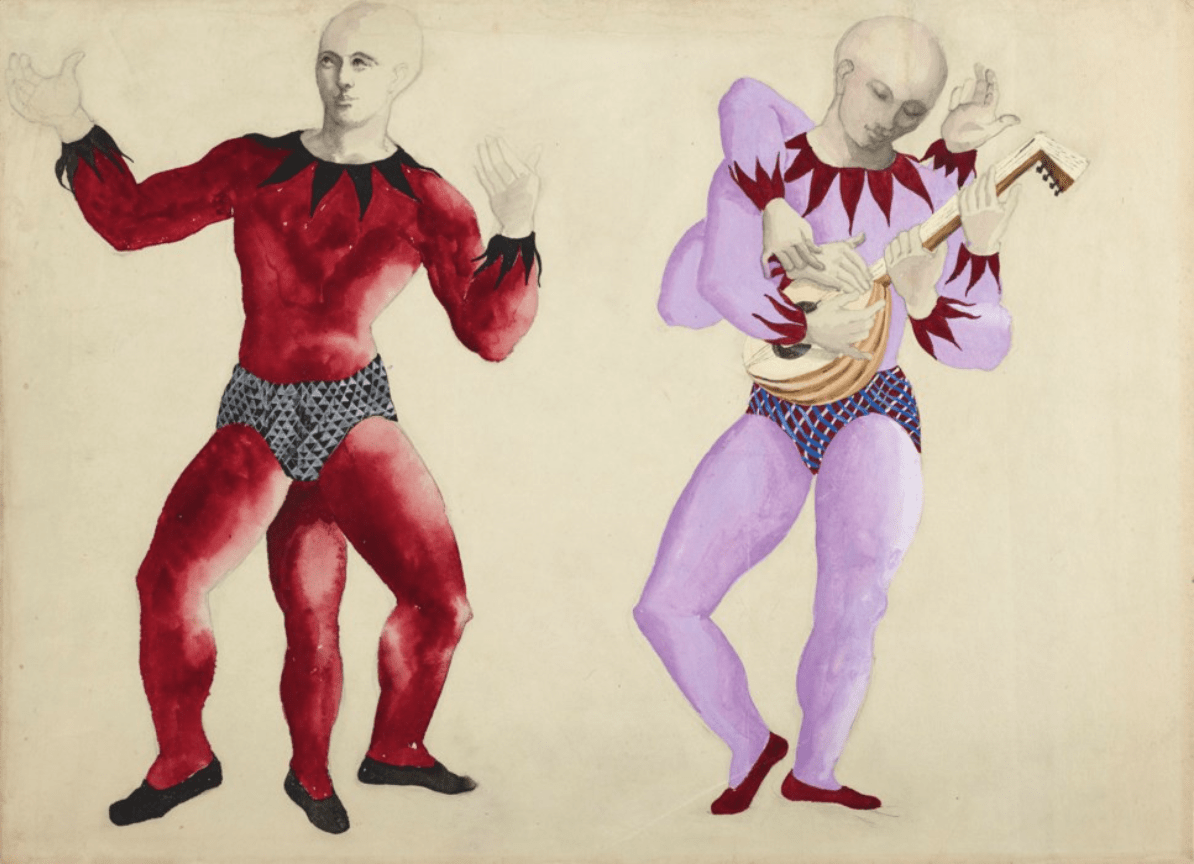

Besides numerous paintings of pleasant peasant scenes in fishing ports, Wood also conjured visionary images from the dark recesses of his imagination. Some were inspired by a carnival ballet called Luna Park, which was organised by the theatrical manager and impresario of popular entertainment Charles B. Cochran. Preparations began in late 1929 and, in November, Wood wrote about it to his friends Ben and Winifred Nicholson, describing the ballet as ‘a tent in a fair [where] phénoménes […] do funny things and dance afterwards.’ Wood designed costumes and scenery. Luna Park was part of the Cochran Revue, opening at the London Pavilion in Piccadilly Circus on 27 March 1930, and was widely admired by many in Wood’s circle. His friend Lucy Wertheim attended four performances.

The performers in Luna Park were cast as acts in a sham ‘freak’ show including a three-headed man and a three-legged juggler. In the narrative, the performers abandon their false limbs and flee the circus, exposing their employer—the showman—to ridicule. The figures depicted in Wood’s painting The Yellow Man are closely comparable to those in his preparatory costume designs for Luna Park. Both aged and doll-like with smooth white heads, the figures of the adult and the child are uncanny. Their fantastical, ghost-like features make them more humanoid than human.

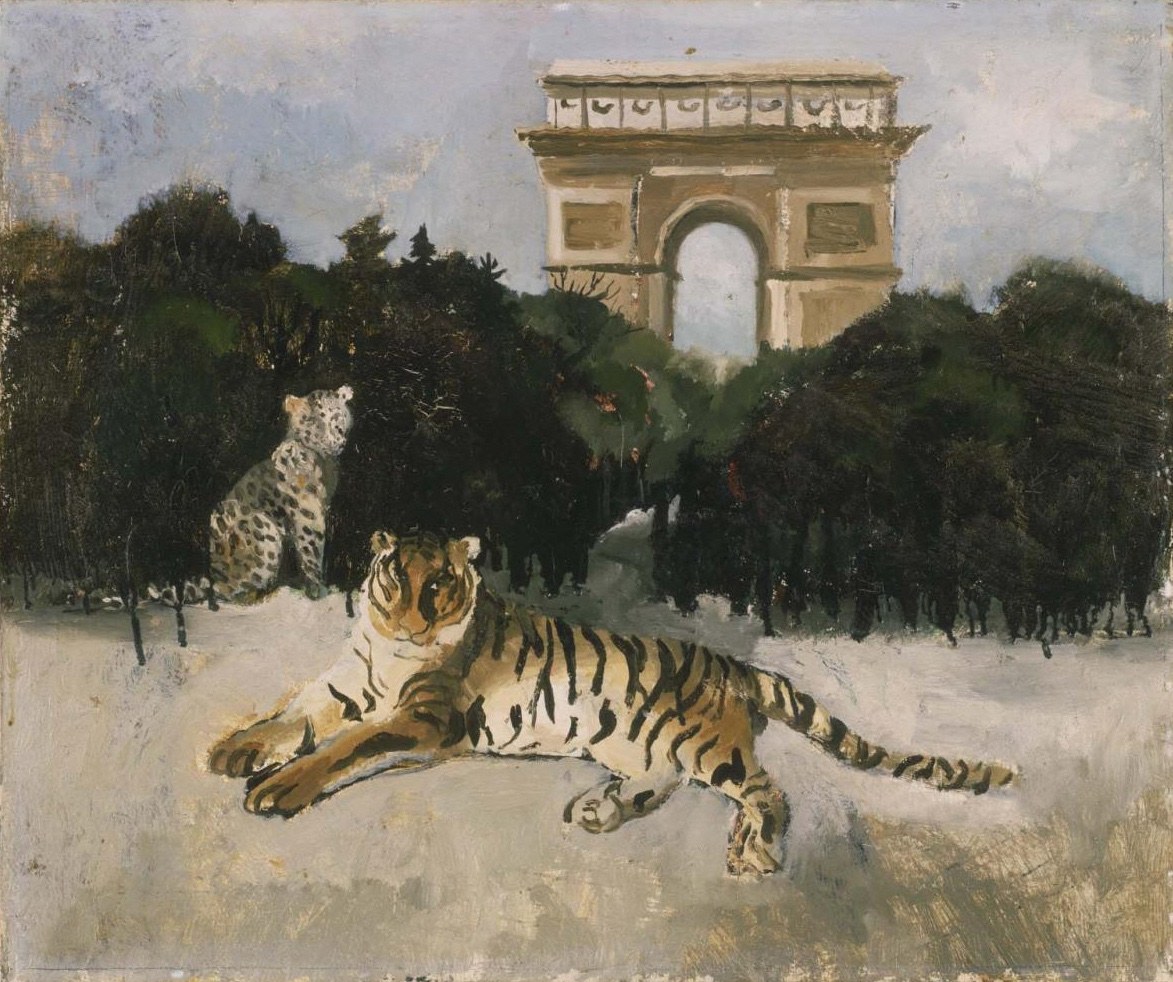

The narrative of Luna Park was written by Wood’s friend Boris Kochno, who reminisced about Wood and the ballet in 1979. ‘To paint, he isolates himself from his friends who suspect nothing of his creative anguish, or his escape into the world of dreams.’ In The Yellow Man, the setting for this ‘world of dreams’ is a narrow muse in Chelsea where Wood lived. Rising above Bury Place, the church tower of St Luke’s is silhouetted in the background against the night sky. To envision such demi-monde performers in an atmospheric London backstreet produces strange, hallucinogenic imagery, which has similar intensity to Wood’s other surreal paintings of the same year such as Tiger and Arc de Triomphe (Phillips Collection) or Zebra and Parachute (Tate). Such paintings are among the most enduring images of British art made in the interwar period.

Almost immediately after Wood painted it in the spring of 1930, The Yellow Man was recognised as one of his outstanding achievements as an artist. His friend Wertheim was a budding art dealer and she bought the painting on 29 March 1930—two days after Luna Park opened. She later wrote in her memoirs, Adventure in Art, ‘It did not take me five minutes to decide that it was quite the best thing he had painted up to date.’ Lady Ottoline Morrell was also an admirer of Wood’s paintings, and The Yellow Man was reportedly one of her favourites. Winifred Nicholson later referred to ‘the nightmare of the yellow ghost’, and the art historian and director of the Tate Gallery John Rothenstein perceived in this painting ‘the emanation of a very rare spirit’. The painting has been included in almost every significant retrospective of Wood’s art, including his memorial exhibition at the Redfern Gallery in 1938.

The subject-matter of The Yellow Man is elusive, but Wood’s imagery and painting style were plain for all to see and digest. After his premature death his work was studied and assimilated by some of his friends, contemporaries and later artists. It formed a bridgehead between the neo-romantic painters of twenties Paris and the nascent neo-romantic movement in thirties Britain. John Piper’s method of darkened scene construction, with panels of shimmering colour and scraped textures, owes an unacknowledged debt to The Yellow Man. Wood’s poetic sense profoundly affected the trajectory of Ben and Winifred Nicholson and how they came to perceive their vocation as artists. Although Wood died before Lucian Freud came of age, Freud learned of Wood indirectly through friends—Cedric Morris, Meraud Guinness, Christian Bérard—and the younger artist’s pin-sharp depiction of fantastic images partly followed from the breakthrough of Wood’s final months. Besides the strange, original imagery of his paintings, Wood’s far reaching influence has made him an essential figure in the history of twentieth-century British art.

Images:

Christopher Wood, Tréboul, 1930, Private Collection

Christopher Wood, Costume Design for Luna Park: The three-legged juggler and the man with six arms, c. 1930, Private Collection

Christopher Wood, The Yellow Man (detail)

Christopher Wood, Tiger and Arc de Triomphe, 1930, Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C.

Christopher Wood, The Yellow Man (framed)