Like Leonardo, Raphael and Michelangelo before him, Henry Moore was a doodler. He liked to doodle and he doodled with the best of them.

InSight No. 143

Henry Moore, Ideas for Sculpture: Reclining Figures, c. 1934/1954

Henry Moore (1898—1986) had a talent for conjuring and transforming simple figure motifs on paper, as demonstrated in works such as Ideas for Sculpture: Reclining Figures. The attitude of a reclining figure is realised in twelve or so different configurations, with the most abstract appearing at the lower left-hand corner of the sheet—an assemblage of arcs and lines organised into interlocking triangles and ovals. Each figure is realised with a suggestion of physical bulk. This leaf was first filled with speculative pencil drawings in the thirties and then overworked, refined and raised to the level of a presentation drawing in 1954. The wash of pale red watercolour created a background, unifying the landscape of the sheet; certain figures were brought to the surface while others were pushed into the background. The largest figures were emphasised by infilling with a wax crayon. Taken together, the contents of this sheet—imagery and graphic techniques—suggest the harmonious interlocking of Moore’s profuse visual imagination and his deft talents for draughtsmanship.

Moore’s talents were admired widely. The name of this drawing’s previous owner is scrawled in pencil on the reverse of the sheet: the Contessa Anna Laetitia Pecci-Blunt (1885—1971), known to her friends as Mimì. She was Pope Leo XIII’s great niece and lived a materially rich life, draped in couture by Schiaparelli and accommodated in the most splendid residences. After her marriage in 1919 to Cecil Blunt, an affluent American banker, she lived in Paris, then in 1929 they settled in Rome in a palazzo overlooking the Piazza d’Aracoeli. It was here that Mimì established an art collection dedicated to the heritage of her home city, which she called Roma Sparita (literally ‘disappeared Rome’).

She and her husband were proprietors of the Galleria della Cometa—initially established in Rome in 1935 and briefly branching out to New York at premises in 10 East 52nd Street—where there was a focus on the work of contemporary Italian artists, among them Giorgio de Chirico. Her interest in Moore’s work was probably motivated in part by her attraction to surrealist tendencies in art. Besides De Chirico and Cocteau, she also owned Dalí’s painting Le chevalier de la mort.

But Mimì’s interests were varied. Besides a significant bequest to the Museo di Roma, she also donated to the Getty Research Institute printed maps and views of Rome, which ranged in date from the sixteenth to the nineteenth century. Her husband also donated two paintings by Corot to the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C

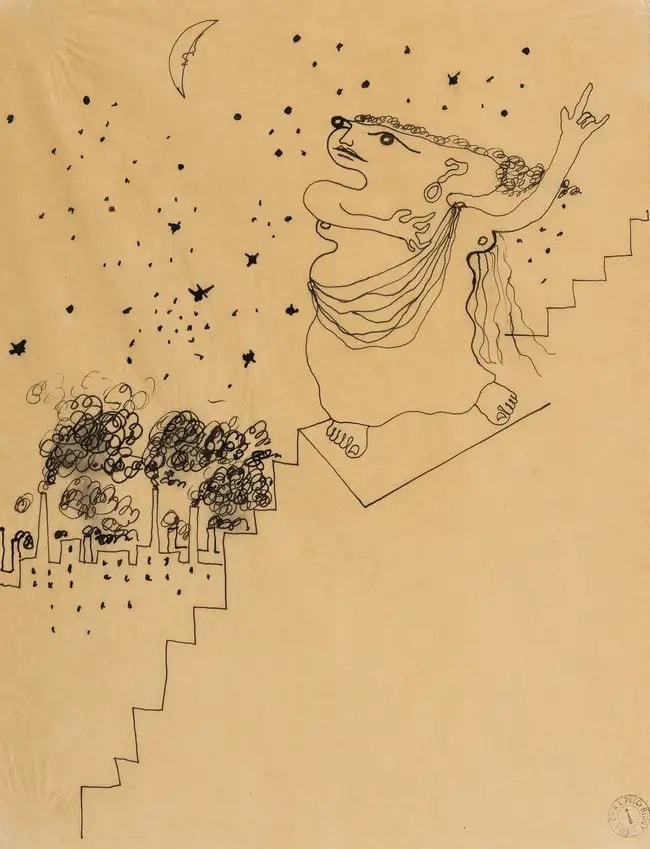

Living in Paris Mimì came to know many eminent artists and musicians. She owned numerous works by Jean Cocteau, among others, and befriended Braque and Dalí. The night sky dense with stars in Cocteau’s drawing La Tragédie Descendant des Degrés, given to or bought by the Contessa, perhaps alludes to her coat of arms, which included a shooting comet. Having established a relationship with various composers and musicians in France, several of them came to stay with her at the Palazzo Pecci-Blunt. Francis Poulenc was a regular visitor whenever he visited Rome.

When considered through the eyes of Contessa Anna Laetitia Pecci-Blunt, Moore’s watercolour Ideas for Sculpture: Reclining Figures can be associated with antiquities from the city whose history her collection sought to celebrate. There is no shortage of reclining figures in the canon of Graeco-Roman sculpture. Moore’s monumental exaggeration of limbs and massive aggrandisement of the human body places his work in a lineage that leads back through the centuries to antiquity. Perhaps Moore’s figures reminded the Contessa of a marble Ariadne in the Vatican Museums, a Roman copy made in the second-century B.C. after a Greek original.

Images

1. Henry Moore, Ideas for Sculpture: Reclining Figures, c. 1934/1954, pencil, wax crayon, chalk, watercolour,

pen and ink, gouache on cream wove paper, 27 x 18 cm

2. Corrado Cagli, Matilde Suvich and Mimì Pecci-Blunt on the Empire State Building, New York, 1937, Archivio Corrado Cagli, Rome

3. Nicolas Beatrizet, Plan of Rome, 1557, Getty Research Institute

4. Jean Cocteau, La Tragédie Descendant des Degrés, 1924, Private Collection

5. Ariadne, 2nd century B.C., Vatican Museums