In the late sixties, John Hoyland took on new challenges in painting just as his life underwent significant personal and professional changes.

InSight No. 134

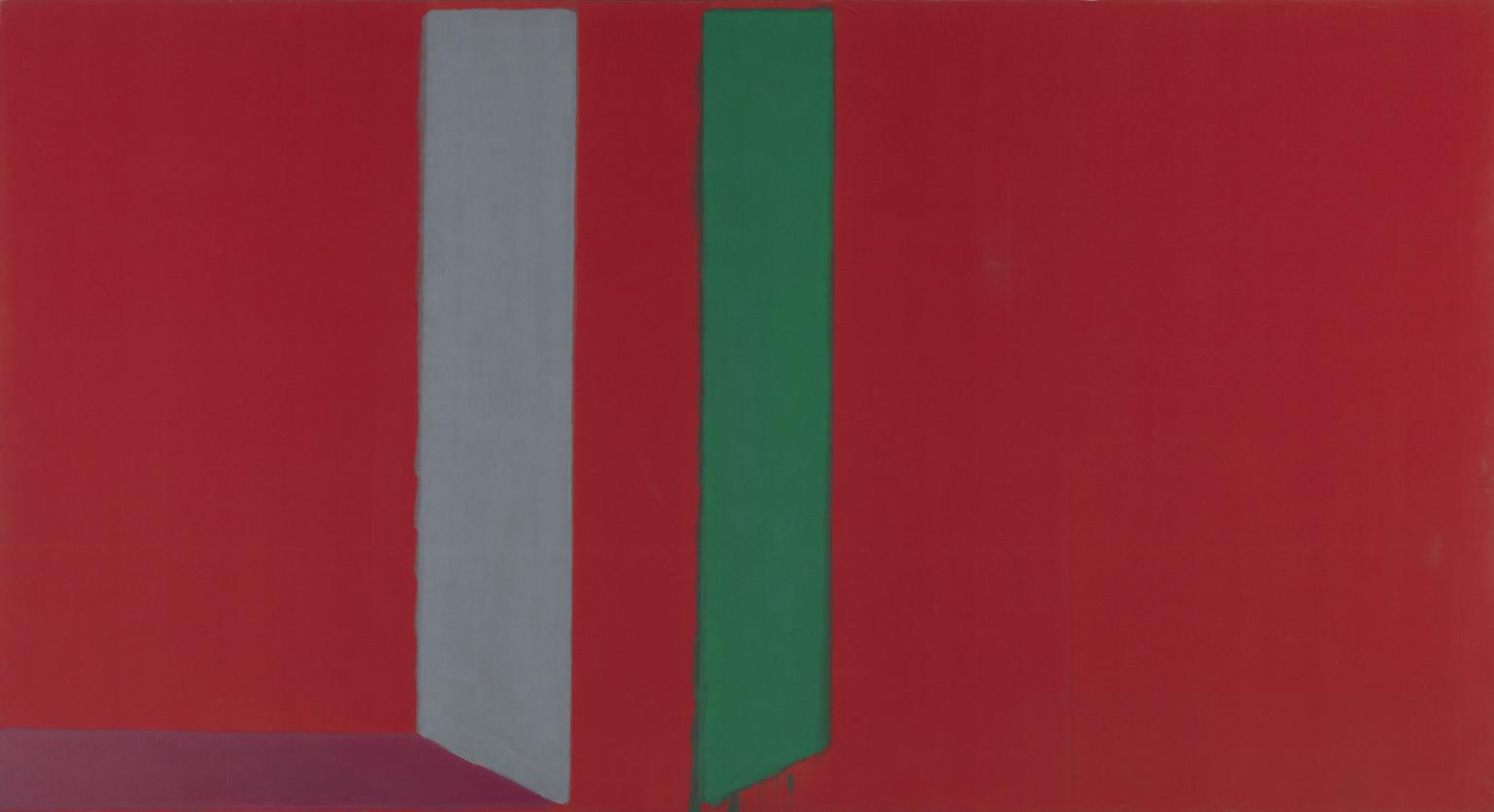

John Hoyland | 20.9.70, 1970

After his solo exhibition at Whitechapel Art Gallery in 1967, John Hoyland (1934—2011) consciously began to seek out new colours. ‘I made myself use all kinds of strange, high-key colour relationships’, he said later. Whereas his paintings of the preceding period were dominated by red and green and the interrelation between planes of colour as flat shapes, the work he made between roughly 1969 and 1978 demonstrates a deepening experimental interest in colour combinations. A painting such as 20.9.70 holds in tension a confounding variety of wilful, unexpected contrasts: mauve beside khaki, cadmium yellow beside chocolate brown, with flesh pink and jungle green set close by. Within a few short years, Hoyland’s experiments had created a pungent new vocabulary in the colour language of abstract painting.

At the same time as he started exploring the uses of colour, Hoyland also brought the plastic qualities of paint into contention. Whereas his previous paintings were made by staining the canvas, much as Mark Rothko had, in 1969 Hoyland began to formulate a more personally distinctive idiom. He accumulated large quantities of paint in concentrated rectilinear shapes, scraping them smooth and allowing them to pool in puddle-like formations of viscous, liquid matter. These rectangles relate to the painted steel sculptures of Hoyland’s close friend Anthony Caro, with whom he represented Britain at the São Paulo biennale in 1969. Around these apparently ‘heavy’ rectangles and squares, dynamic constellations of poured and splattered paint forms – contrastingly ‘light’ and weightless by contrast – began to orbit. In the case of 20.9.70 some areas of the canvas were left bare, and the exposed canvas came to represent a deep field from which built-up layers of acrylic, added sequentially one on top of the other, seem to project outwards.

When asked in 1986 about his preference for acrylic over oil paint, Hoyland evoked its novelty value – it was an exciting new product when he was a student and he recalled how it was ‘heralded as being a new “magic” material that would transform art’. As a water soluble medium, he appreciated its transparency, and he also used it to create gelatinous textures. Above all, he prized its staying power: ‘When acrylic is dry that’s it – you could hit it with a hammer!’

The pooling of paint in 20.9.70 was enabled by working with the canvas flat on the floor. Whereas Jackson Pollock had made his dripped and poured paintings on unstretched canvas, Hoyland’s stretched canvases allowed him to pour large quantities of paint and then position them by tipping the rigid plane this way and that. Acrylic paints do not mix together easily and the interaction of unmixed paints in 20.9.70 created an effect akin to marbling, which further deepens the variety and material complexity of the finished paint surface.

Changing personal circumstances formed the background to these formal developments. Hoyland’s marriage ended in 1968 and he acquired a disused chapel in Market Lavington, a village in Wiltshire, which he adapted as a home and studio. A subsequent relationship with the singer Eloise Laws between 1969 and 1973 led him to spend extended periods in the United States, especially New York where he had a studio for a time. Following his Whitechapel show, he was freed from the financial necessity of teaching. After he joined Waddington Galleries in London and began to exhibit at André Emmerich Gallery in New York, in the words of the art historian Mel Gooding ‘he was launched on a highly successful international career.’

Hoyland’s experimental attitude and his technical innovations were noted by a later generation of artists. The inaugural exhibition at Damien Hirst’s Newport Street Gallery in 2015 was dedicated to Hoyland and paintings he made between 1964 and 1982, and the scraped layers and unmixed intermingling of paint in Hoyland’s paintings bear a passing resemblance to Hirst’s spin paintings. Also following Hoyland, the painter Fiona Rae has used acrylic in carefully poured and tipped arrangements. These traces of Hoyland’s practice in the art of a younger generation suggest the originality of his work, and the lens of contemporary art practice only serves to magnify the freedom, ingenuity and unconventional wisdom in Hoyland’s art.

Images

1. John Hoyland, 20.9.70, 1970, acrylic on canvas, 177.2 x 127 cm

2. John Hoyland, 28.5.66, 1966, Tate © The John Hoyland Estate

3. 20.9.70 (detail)