Long before the era of paper cups and over-the-counter service, Duncan Grant and Henri Matisse savoured the civilising effects of the coffee ritual.

InSight No. 128

Duncan Grant, Still Life with Fruit and Compotier, circa 1919-20

Duncan Grant (1885–1978) liked coffee. Throughout his long career, his many various coffee and café-au-lait pots appeared and reappeared in his paintings. Henri Matisse also liked coffee, a fact that speaks to an important affinity between him and Grant. Underpinning their work, there existed an ethos of profound, serious and sophisticated leisure. In Matisse’s Luxe, Calme et Volupté, the white cloth laid with coffee things at the lower left-hand corner establishes and enhances the ideals listed in the painting’s title. Taking coffee recurs as a leitmotif in this and other pictures, and this staged activity might be taken to represent a whole category of other pursuits – all prosaic, all valuable for their civilising effects.

Such art was essentially middle class. This was acknowledged by the critic Robert Hughes, who said that for Matisse ‘an educated bourgeoisie was the only audience advanced art could claim’. Rather than bridle, as many others did, this ‘educated’ audience responded with interest to a modernist idiom of flattened, keyed up, factive paintings, and it was this idiom in which Matisse and Grant conceived their paintings of the coffee ritual. For the previous two centuries or so, domestic narratives of coffee and teatime had been depicted with conventional respectability by the likes of James Tissot. The modernist vanguard transcended these banal reflections of reality, instead harnessing this subject to project its values.

The values established by Grant and Matisse were later familiar to Howard Hodgkin, who admired the ‘great lyrical gift’ he perceived in Grant’s early career. Sensory richness and the seriousness of leisure were also important themes in Hodgkin’s work. Although he apparently preferred tea to coffee, paintings such as Tea with Mrs Parikh (1974-77), Cafeteria at the Grand Palais (1975) and Tea (1977-80) witness his commitment to expressive forms of patterning that grew in part from the leisure ideal of Grant and Matisse.

In each of these artists’ paintings, elaborate painterly surface effects and intensified, sometimes exaggerated colouring are inseparable from the underlying mood of pleasure and domestic comfort. In the case of Grant’s painting Still Life with Fruit and Compotier, objects – cup and saucer, coffee pot, compotier with fruit – are depicted in real space using consistent lighting and single-point perspective. Yet they are flattened into the plane of the tableau, appearing as shapely decorative extensions of the daffodil motif that ornaments the tray on which they are arranged. This decorative flattening is also implicit in Grant’s execution. The entire surface is painted with clean touches of a loaded brush and appears fastidiously uniform. The same depth of impasto is used over the whole surface. The result accommodates simultaneous perceptions of a vivid, beautifully painted flat surface and a spacious, fully realised scene, in which real objects occupy a fixed position and displace a specific amount of volume.

Grant’s painting belongs to an era before the globalised trade in fruit. The apples and medlars in his compotier were grown at Charleston, the farmhouse in Sussex that he and Vanessa Bell moved to in 1916, and an apple loft there allowed apples to be kept in winter and through the year. Apples were a loaded subject for Grant and his circle. Roger Fry wrote of how Paul Cézanne posed for his self-portrait ‘as an apple’. In 1918, Maynard Keynes returned from Degas’s studio sale with a small panel painting by Cézanne, and Virginia Woolf saw it shortly after it arrived at his house in Gordon Square:

There are six apples in the Cézanne picture. What can six apples not be? I began to wonder. There’s their relationship to each other, & their colour, & their solidity. […] The apples positively got redder & rounder & greener. I suspect some very mysterious quality of potation in that picture.

There are eight apples visible in Grant’s painting Still Life with Fruit and Compotier. But for Cézanne, they might not look so solid and so present. But for Matisse, they might not look so delicious.

Images:

1. Duncan Grant, Still Life with Fruit and Compotier, circa 1919-20, oil on paper laid on cloth, 44.5 x 58.5 cm

2. James Tissot, Tea, 1872, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

3. Howard Hodgkin, Tea with Mrs Parikh, 1974-77, Private Collection © Estate of Howard Hodgkin

4. Paul Cézanne, Still-life with apples, circa 1877-1878, Provost and Fellows of King's College, Cambridge (Keynes Collection)

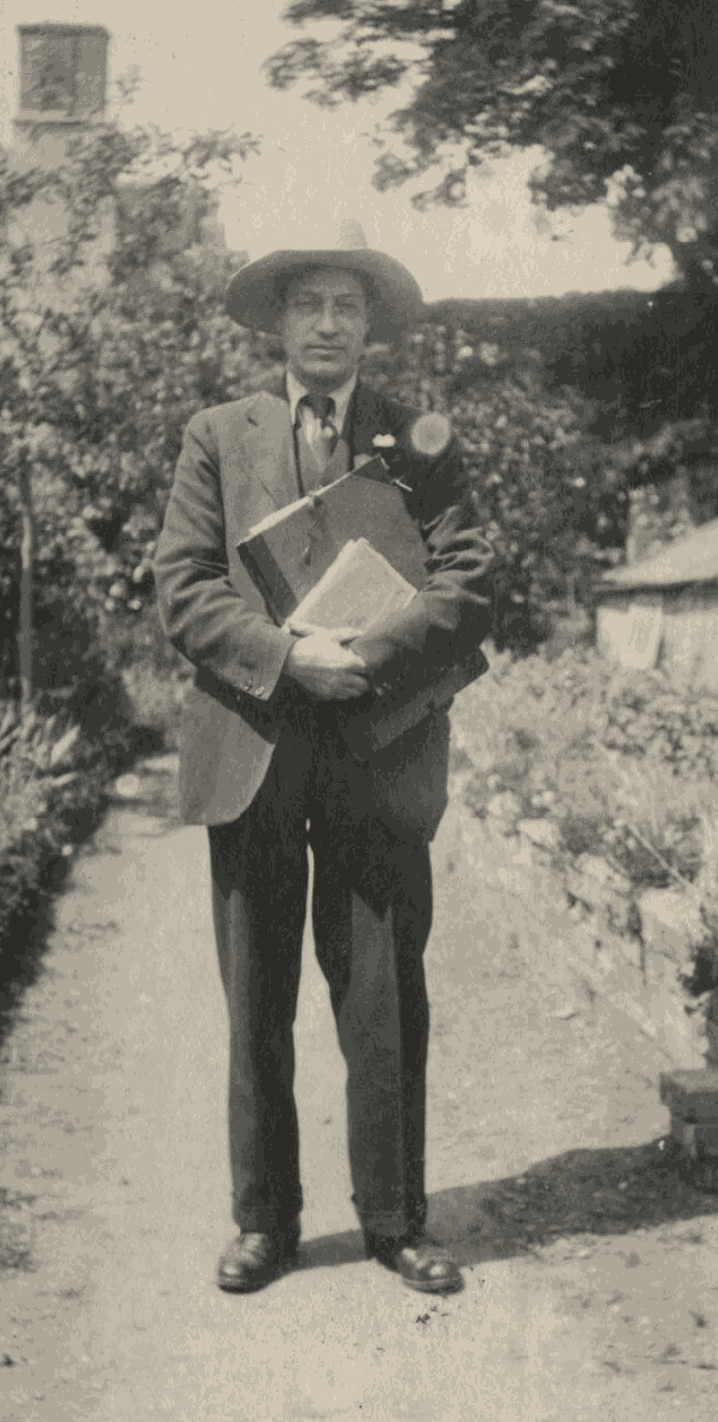

5. Duncan Grant, 1922, photographed by Lady Ottoline Morrell © National Portrait Gallery, London