This bank holiday, set sail for Euan Uglow’s painted desert island paradise.

InSight No. 124

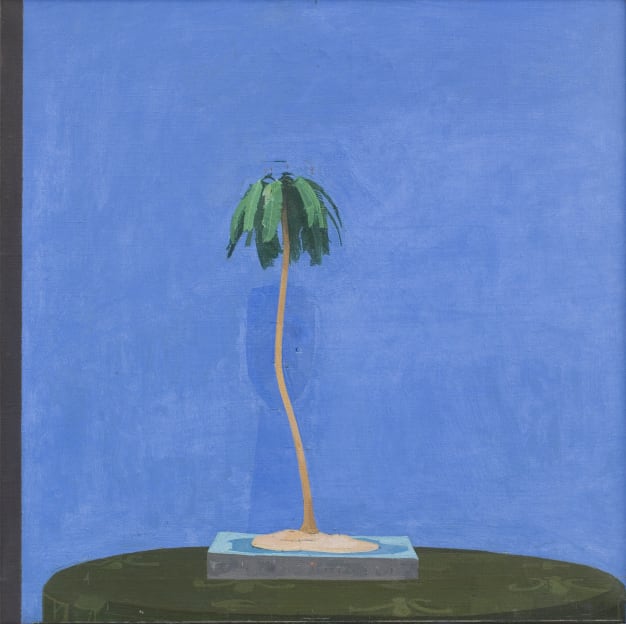

Euan Uglow, Palm Tree, 1971

The remote desert island has a firm hold on the popular imagination. In the present era of cheap commercial travel and long-distance flights, the notion of an inaccessible place has become deeply attractive, much as the era of colonialism was once drawn to ‘the orient’. The philosopher Roger Scruton described distance as ‘that precious commodity without which people no longer belong where they are’, and the desert island is the cultural ideal that complements the reduction of vast distances by high-speed trains and planes. The appeal of these nowhere places is broad: some billionaires are noted for their ownership of private islands; popular motion pictures like Cast Away show their heroes enacting a modern pastoral, involuntarily cut off from the comforts of civilisation; Desert Island Discs has been asking its guests since 1942 which records they would like to be marooned with. The desert island is also an unfailing source of inspiration to the imagination of humorous cartoonists.

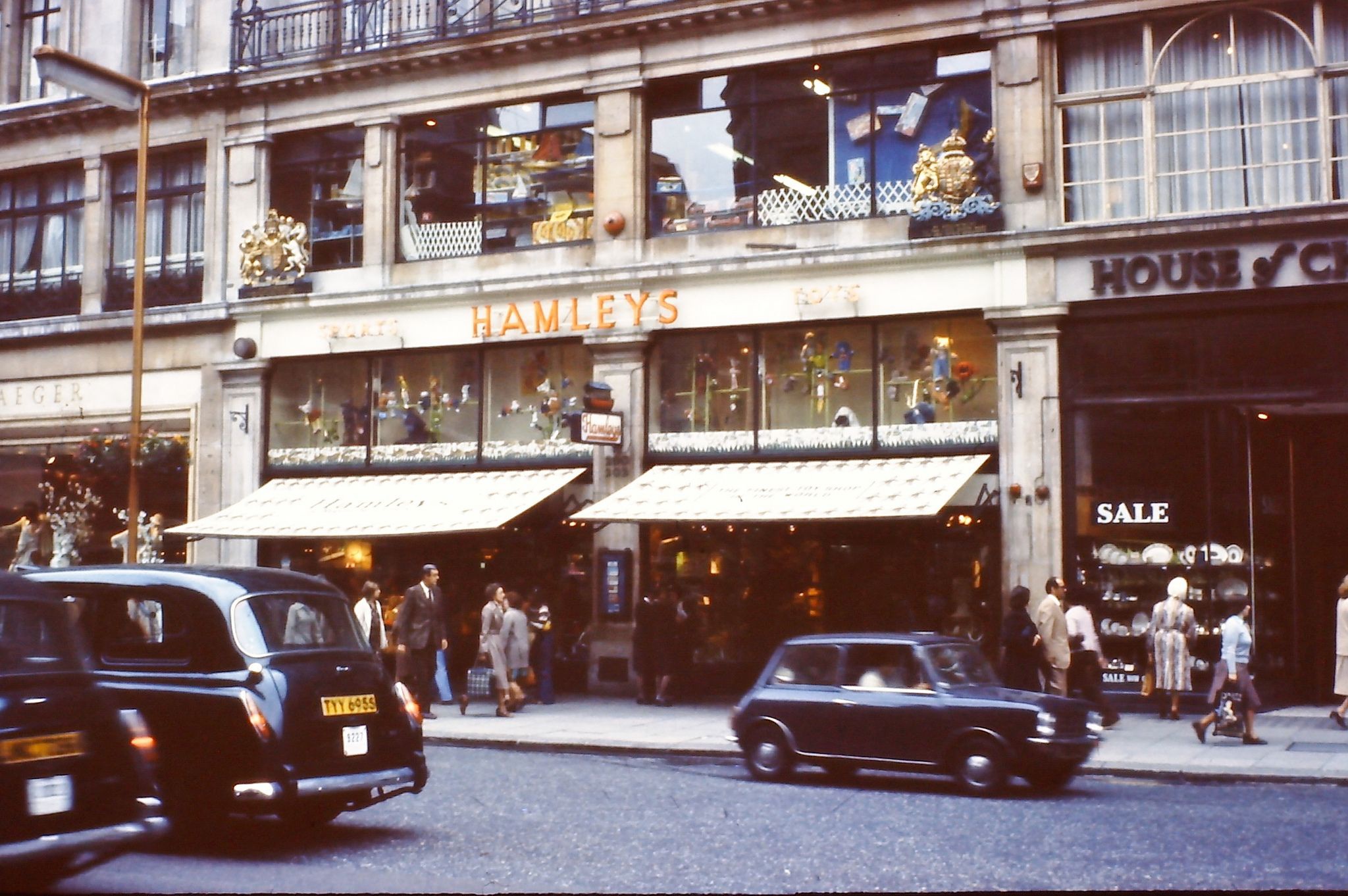

Euan Uglow (1932–2000) took pleasure in appropriating and subverting such cultural ideals. His painting Palm Tree relies on a witty conceit, at once simulating the stereotypical desert island – a single palm, a spit of land, the lap of blue water and even bluer sky – while exposing the scaffolding from which the scene is constructed. The palm is no more than a small model with plastic leaves and a metal trunk, purchased from a toy shop as a gift for Uglow by his friend Craigie Aitchison. It was later modified, with the base painted a sandy colour and set on a square block. Likewise the green tablecloth with a fleur-de-lys pattern, also apparent in another of Uglow’s still-life paintings, Georgia’s Roses (1973), and the narrow stripe of dark grey along the left-hand edge of the canvas, both of which create pictorial tension within the idyllic imagery of a desert island.

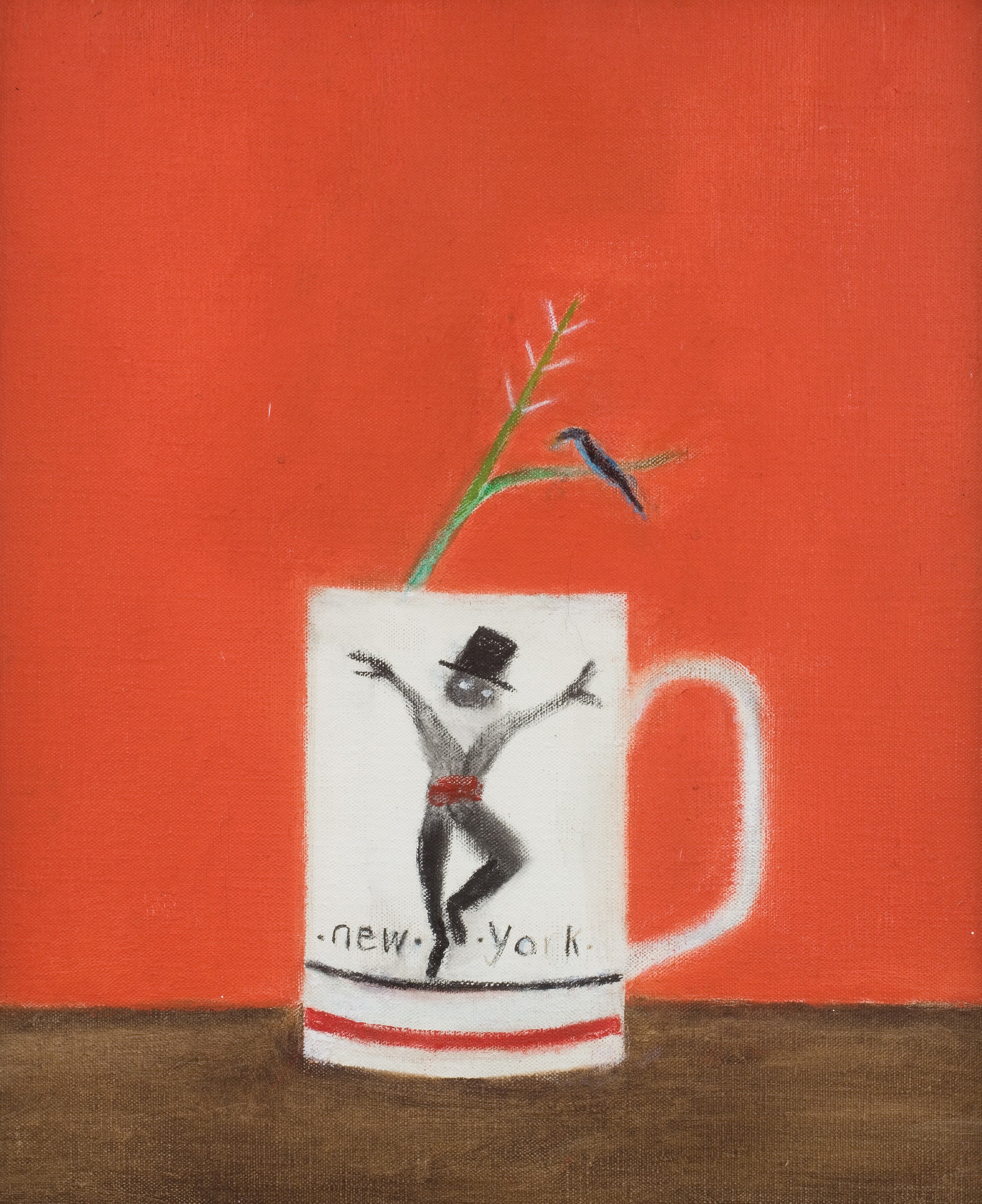

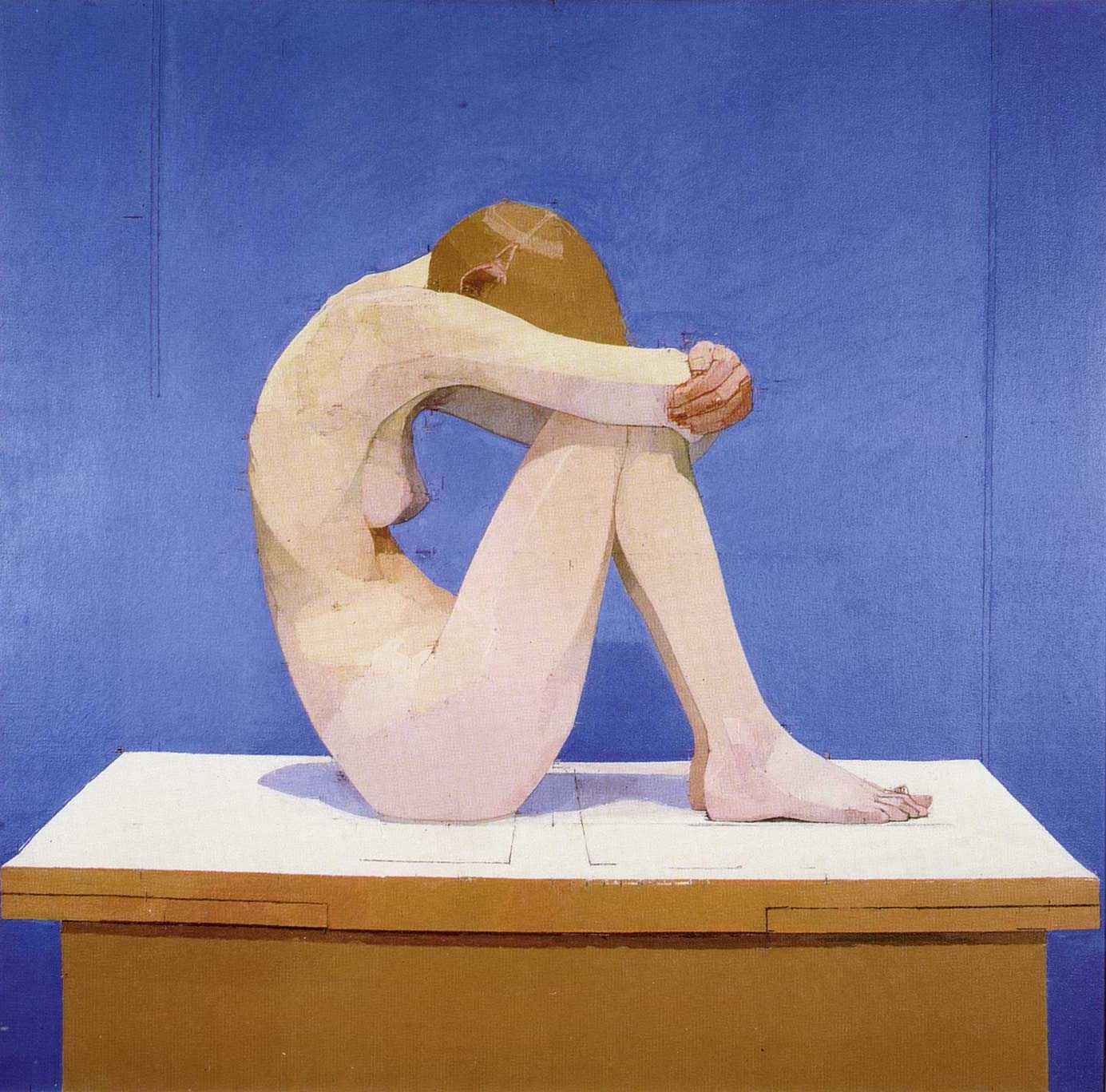

Like his friend Aitchison, who also used unconventional objects as still-life subjects (kitsch mugs and religious ephemera included), Uglow negotiated a visually satisfying path between the need for pictorial ‘rightness’ and a keen interest in strange, off-beat materials. In Uglow’s hands, even a banana or a toothbrush could look mysterious and remarkable. Writing in 1997, the art critic Martin Gayford tried to explain this achievement with reference to the supernatural: ‘Conjuring poetry like this from precision, mystery from mathematical exactitude, abstract yet figurative, is a kind of magic in art.’ Uglow’s peculiar choice of subjects was underpinned not only by a fascination with the oddity of how things look, but also a restless humour and a piquant delight in puncturing the bubble of art. Transferring a toy palm tree into paint is pictorially ingenious; it is also faintly transgressive.

In both the application of paint and the fastidious construction of perspective, Uglow’s paintings demonstrate a critical attitude to the elementary, long-established components of picture making with oil paint on canvas. Explaining his method to Andrew Lambirth in 1989, he said:

[I]t’s new every time. […] There are no generalisations, every picture is different. […] I like to have an ordered rectangle, a shape with reason. The whole picture is glued together with the shape of the canvas and the appearance of the subject. The measurements will be to do with the shape of the rectangle. I take measurements so that the subject has a real link with the rectangle; it also gives me freedom to make a whole surface.

In Palm Tree, the depth of field is extremely shallow. Both the round table and the square block on which the palm tree stands are steeply foreshortened. When viewed from an acute angle, regular shapes become disfigured as they contract. When such contracted shapes are recreated as a picture on a flat surface, the distortion is magnified even further. Such commonplace optical effects were grist to Uglow’s mill and he ground them thoroughly and with abandon. Around the palm leaves, a net of ‘obviously two-dimensional’ marks provide relative measurements, communicating to Uglow the relation of the object to the surface of the canvas. In contrast to these narrowly precise arrangements the blue of the wall beyond is spacious and expansive. It was used in several other pictures by the artist, a paint reportedly made by the artist himself using finely ground washing powder as pigment. In Palm Tree, this wall is made to suggest an infinite expanse of sea and sky.

Images:

1. Euan Uglow, Palm Tree, 1971, oil on canvas, 44.2 x 44.2 cm

2. Hamleys, Regent Street, photographed in 1978

3. Craigie Aitchison, 'New York' Still Life, 1989, Private Collection © Estate of Craigie Aitchison, courtesy of Piano Nobile, London

4. Euan Uglow, Summer Picture, 1971-72, Private Collection © Estate of Euan Uglow