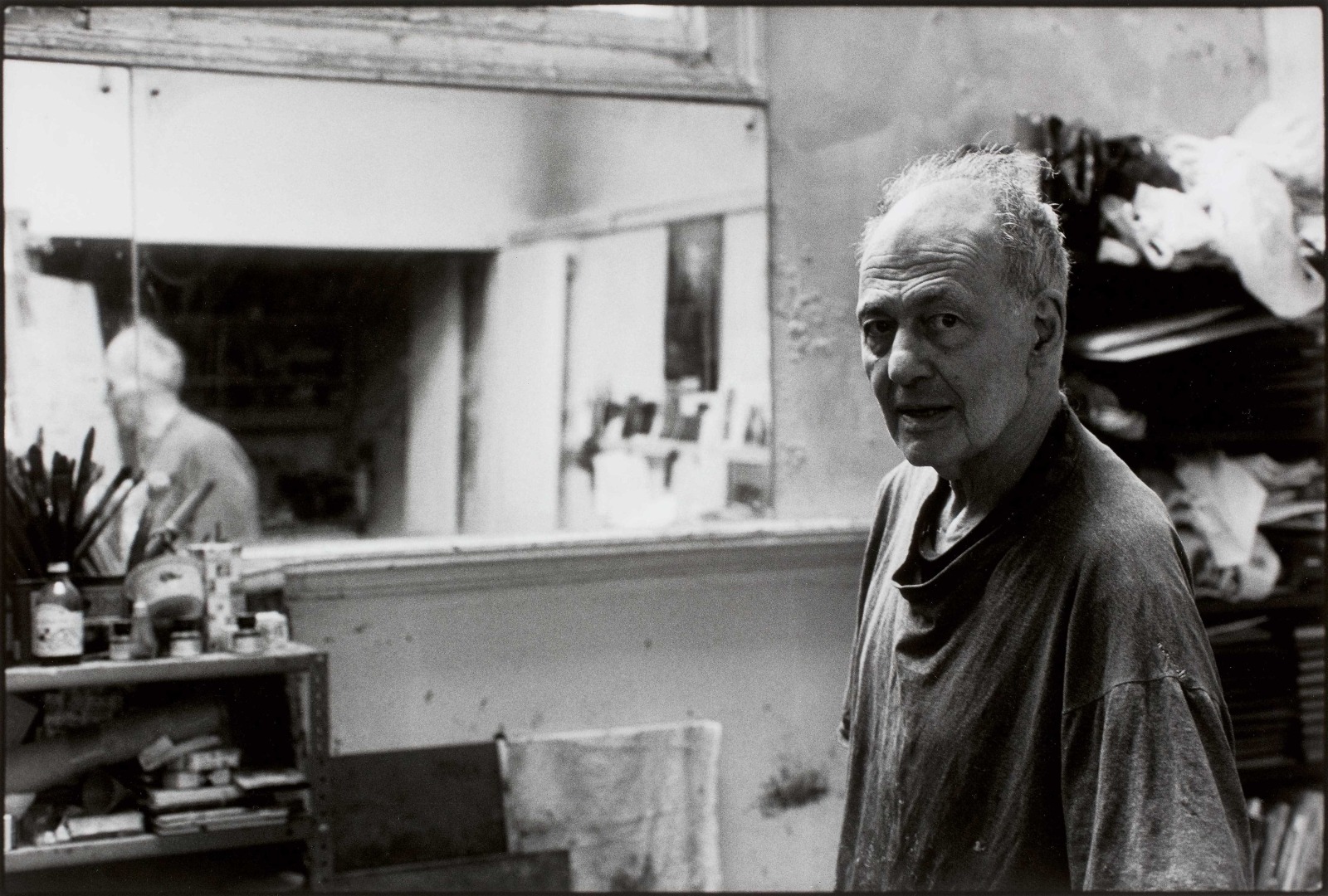

To mark the opening of Piano Nobile’s exhibition Frank Auerbach: The Sitters, InSight considers the recent work of Britain’s greatest living painter. A remarkable thread of continuity ties together his earliest work with his latest.

InSight No. 110

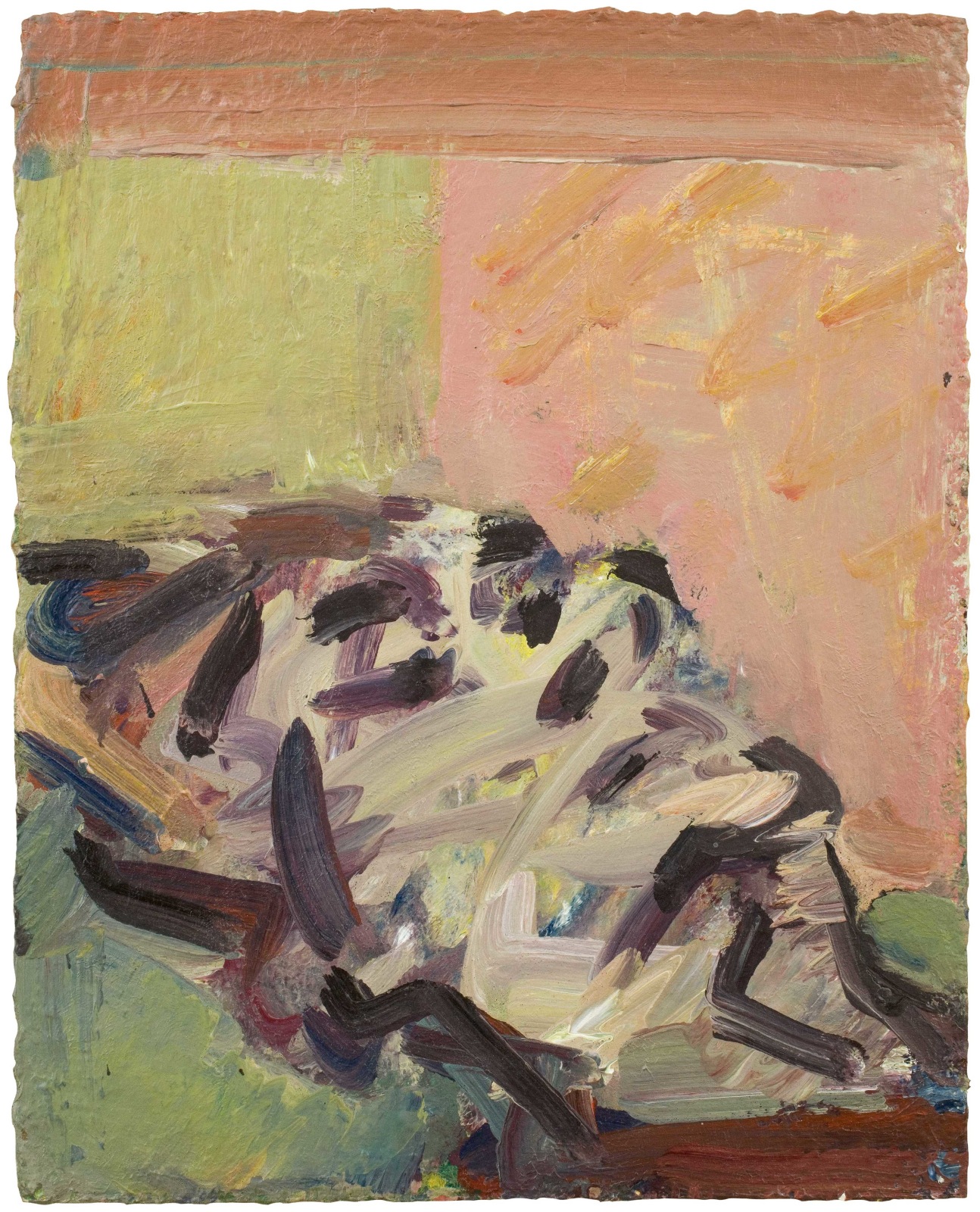

Frank Auerbach, Reclining Head of Julia, 2020

In 1963, a gifted young undergraduate called Michael Peppiatt wrote to Auerbach and asked him about his work. Auerbach’s courteous reply was published in the journal edited by Peppiatt, Cambridge Opinion, in January 1964. He explained how he knew when a work was finished, and he has continued to explain this in largely similar terms ever since. There are two criteria: the picture has to be new and it has to be true. In his own words, the image must seem both ‘unfamiliar and crazy’ and ‘banally and obviously like the subject’.

Over the decades, only Auerbach’s female sitters have modelled lying down. Stella West, J.Y.M., Gerda Boehm and his wife Julia have all done so. Auerbach has spoken appreciatively of ‘these unfamiliar angles of the human head’ produced by viewing a recumbent model from under the chin. The legibility of the human form weakens as an irregular geometry of chin, nose and cheekbones takes over. Painted in the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic when his other sitters were unable to visit because of social distancing measures, Reclining Head of Julia returns once again to an unfailing source of interest: the strange, vivid aspect of a foreshortened face.

In an interview with Martin Gayford in 2001, published in an extended version for Frank Auerbach: The Sitters, Auerbach explained how he interacts with the wide field of historical art.

The exciting thing about painting is that this ground has been so tilled and gone over and manured – there’s so much richness in it – that it’s very clear whether what you do is going to add even the tiniest grain of sand to this thing.

To him, there is no separating painting in the present from painting in the past. The work of Giotto, Velázquez and Cézanne, for instance, erects an inescapable standard against which Auerbach judges himself. One of the first published accounts of sitting for a portrait by Auerbach, given by his friend the art historian Michael Podro in 1978, mentioned how the artist ‘would frequently have books on the floor open at portrait heads by Dürer or Hals or Rembrandt’. Podro said these illustrations were ‘pacing him, […] setting up a standard of articulateness which he had to try to match.’

In Auerbach’s portraiture, the accommodation of a living, breathing sitter with half a millennium of easel painting produces an extraordinary marriage. It takes time (sometimes a generation) for the most advanced image-making to become familiar and generally comprehensible. Yet even as Auerbach’s work comes to be more widely understood, there remains something irreducible and exciting in these images. In a conversation with Catherine Lampert in 1978, Auerbach described how a successful work of art will forever continue to look ‘disturbing and itchy and not right’.

A comparable manner of ‘itchiness’ is apparent in Walter Sickert’s painting The Servant of Abraham. Rather than describe the facial features, wild brush marks approximate to them. In both Sickert’s painting and the many heads made by Auerbach over his lifetime, the form is made to live again by an inventive recreation in oil paint. In Auerbach’s generation, the grail of painting was to lock together uninhibited mark-making and the convincing evocation of living flesh. Along with Francis Bacon, Lucian Freud and Leon Kossoff, Auerbach found the grail. His portraits are today recognised as some of the most extraordinary images produced by any artist in Britain after the Second World War.