Internationally renowned and highly inventive with his materials, most notably his adoption of the plaster-like substance Stolit, Lynn Chadwick was one of the leading sculptors of the post-war period.

Lynn Chadwick (1914–2003) is the rare case of a post-war British sculptor to receive international recognition. Beside Henry Moore and Barbara Hepworth, Chadwick won acclaim for his contributions to the British Pavilion at the Venice Biennale in 1952 and 1956. These exhibitions were noticed by the distinguished American collector James Thrall Soby, who subsequently bought Chadwick’s work The Seasons (1956) and hung a portrait of the sculptor on the wall of his home in New Canaan. Chadwick is one of the esteemed British sculptors represented in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

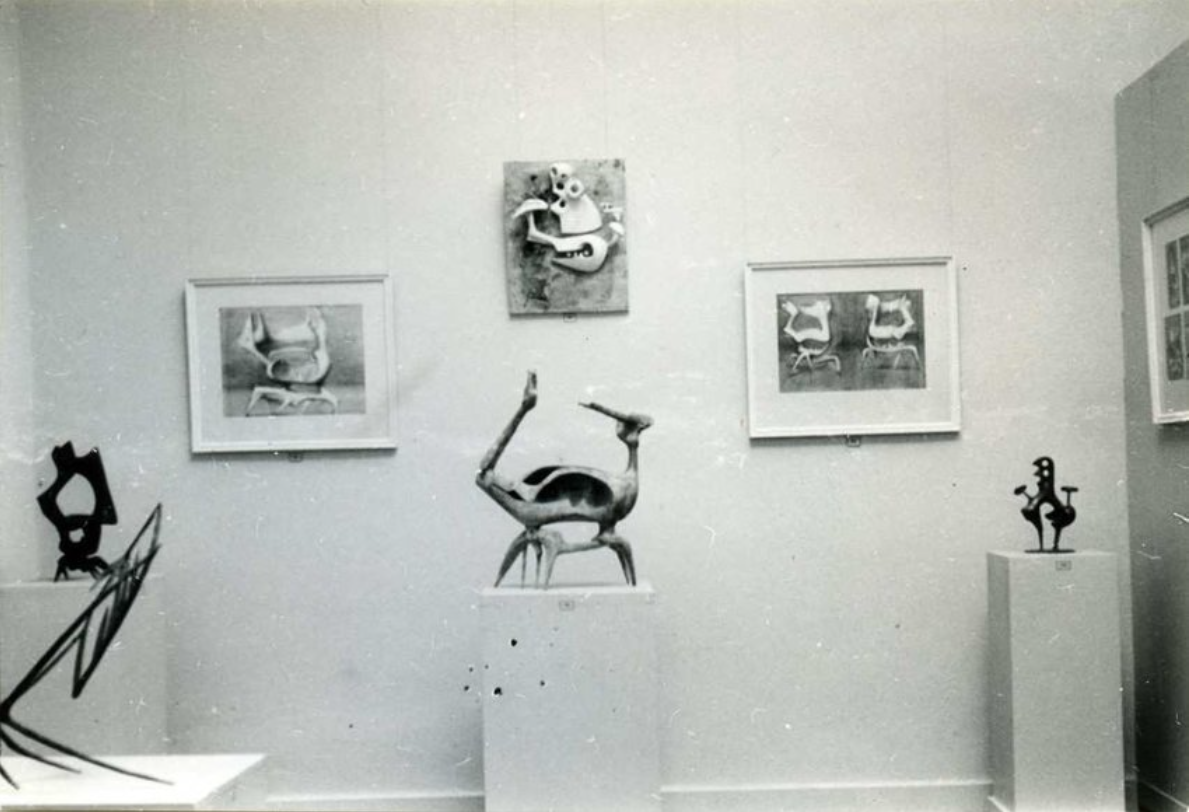

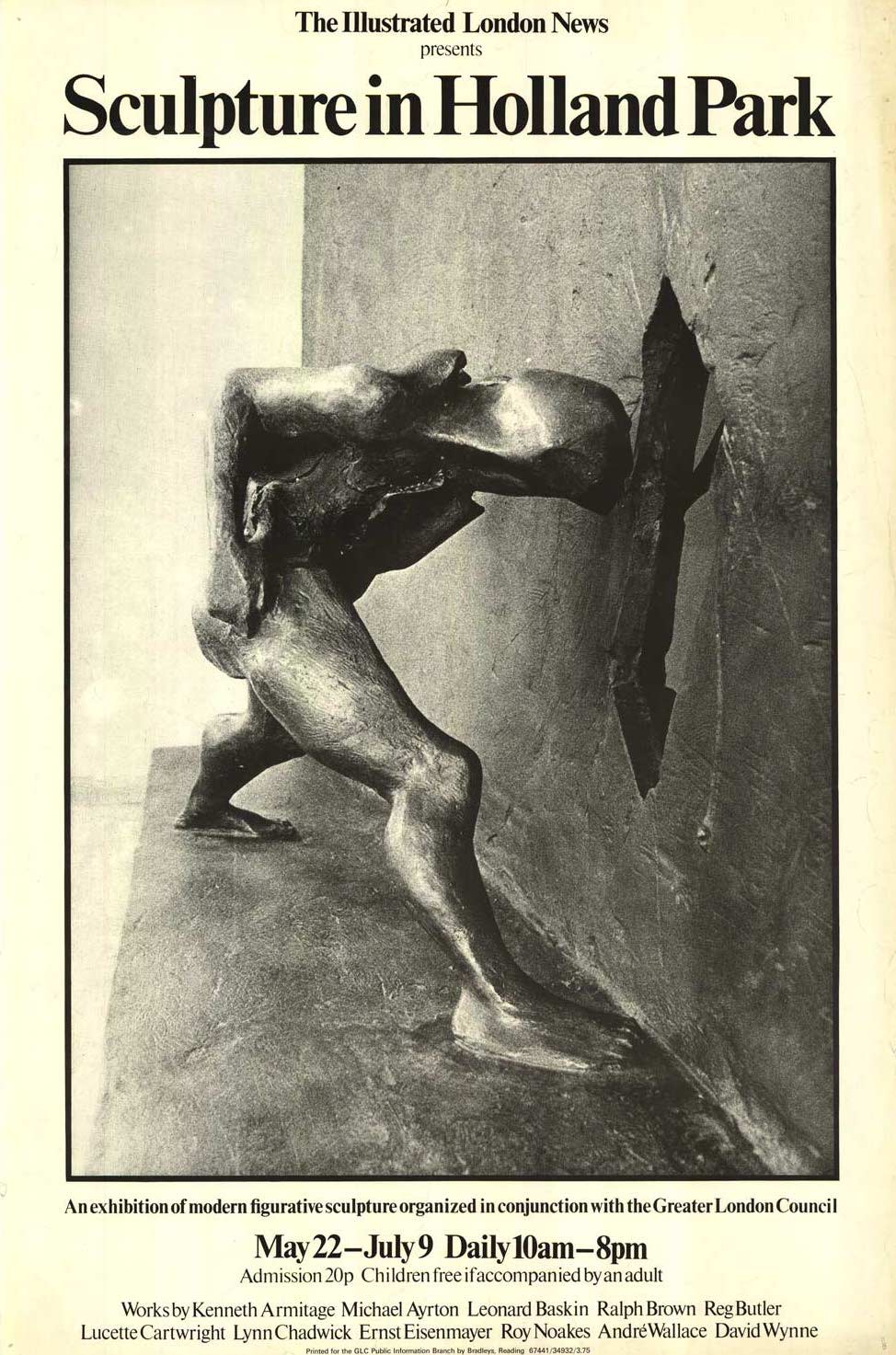

By the 1960s and ‘70s, Chadwick’s work was being shown regularly in solo exhibitions around the world. In 1965, he was at Knoedler in New York; in 1966, he was at the Musée National d’Art Moderne in Paris and Galerie Günther Franke in Munich; in 1968, he was at Galerie d’Eendt in Amsterdam; and so on. The regular pattern of exhibitions in Europe and North America continued throughout this period. Closer to home, in 1975 Chadwick was included in an outdoor showing of ‘modern figurative sculpture’ in Holland Park, a stone’s throw from where Piano Nobile is today.

Every figural artist has to reconcile the human body with the constraints of their medium, compromising and coercing flesh and artistic fabric into a satisfactory relationship. In Chadwick’s case, a human presence was always implicit in his sculptures, even as the elementary composition of three- and four-sided planes provided the framework for representation. In Seated Figure I, as with much of his other work, the characteristically un-armed body is evoked using a succession of stepped and jointed planes: the back of the figure is forcefully composed from a jaw-like set of interlocking isosceles triangles, an elegant conception which speaks of metalwork rather than skin. Yet Chadwick’s figures are human, they have body language and character, and as the sculptor himself said, ‘they all have their own thing to say’.

In an extended interview for the British Library’s ‘National Life Stories’ project, Chadwick spoke of his figures in terms of ‘alignment’, ‘stature’ and ‘stance’. The artist’s ingenuity lay in the fluent construction of a supple, poised figure from materials and surfaces which are purged of human content. Skin is replaced by patina, a richly scraped and pitted envelope which nevertheless contains a human form. At once maintaining and resolving this contradiction was one of the great achievements of non-naturalistic British figure sculpture in the twentieth century, an achievement which Chadwick contributed alongside Henry Moore and Barbara Hepworth.

Writing of Chadwick’s work from the 1970s, his monographer Michael Bird has described how ‘[t]he male forms tend to be angular, […] made from steel and Stolit but recalling the hand-formed surfaces of ancient terracotta from Tanagra.’ Stolit, a cement made from plaster and iron filings, was an original choice of material – not previously used in sculpture – which Chadwick first adopted in the 1950s. The material helped him to achieve in his models a distinctive scabrous texture, applying the plaster over the figure’s basic steel armature to build up the desired shape and a continuous surface. The shape and rippling texture of the model was then transferred without deviation into a bronze cast.

In a work like Seated Figure I, so enriched by specked and nuanced faces of metal, there is a temptation to attribute the rich texture either to the bronze casting process or even the bronze itself. This is an error, however, and the texture is in fact that of plaster, reproduced in bronze. An ingenious play on materials is at work in Chadwick’s sculpture, translating supple and carefully worked surfaces into the solid, monumental, patinated bronze of the finished object.