The landscape art of Paul Nash (1889-1946) encompasses both modernist impulses and a traditional rural life.

Paul Nash

Spring Landscape, 1930 c.

Though today he is most appreciated for his modernist and surrealist tendencies, Nash's naturalistic landscape work has a tautness of design and occasionally a twist in its tail that distinguish it from the more staid output of contemporary landscapists like Gilbert Spencer and his brother John Nash. Unlike conventionally bucolic views of southern England, evoking this plane or that hill as static, topographical entities, Nash often gave his paintings the sense of something happening. A bird flies across the wood, branches sway in the breeze, trees stand watch on a hill, water trickles down a path. In an encounter with this art, the viewer discovers something with its own pulse - a living place which is at once mediated and constructed by Nash's picture.

Spring Landscape was most likely made in the mid-1930s, a period when Nash was treating a mixture of stylised and naturalistic subjects as well as using more saturated watercolour effects. He had yet to make his now famous surrealist objects and photocollages. Stylistically, this dating is suggested by the open-knit compositional structure in which several elements - notably the foreground - are left to the white of the paper. After 1935, Nash's work became increasingly dependent on photographs he took, with his health preventing him from working out of doors and the monochrome source material directing him towards exaggerated, non-naturalistic colouring. The grey, green and russet tones in Spring Landscape suggest an act of direct observation, unmediated by photography.

The size of Spring Landscape is untypical in Nash's output. In height, it measures slightly less than the regular dimensions of his small-scale plein air studies of this kind. Many other works measure roughly seven by ten inches, while almost no other has this work's size and proportions. The paper was evidently shaped specifically for this subject and the subtly tapered edges suggest this was done with a pair of scissors. The narrow proportions help to emphasise the flowing, gently sloped line of the horizon, which runs unbroken across the picture.

The lie of the ploughed field, summarised by alternating bands of contrasting colour, features prominently in Spring Landscape. A pastoral theme is implicit in naturalistic pictures of this type by Nash, evoking ideas of produce, settlement and a rustic country life. He took many photographs of ploughed earth, cropping the horizon line to the upper edge of the image and relishing the texture and formality of the furrows. In one image, however, taken at a farm in Gloucestershire, Nash turned to the Edenic life of the plough: a man and his horses, quietly going over the field. Taken in the last decade or so when animal-led ploughs were the norm, before the advent of machinery after the Second World War, this photograph - like Spring Landscape - belongs to a rural culture that has long since disappeared.

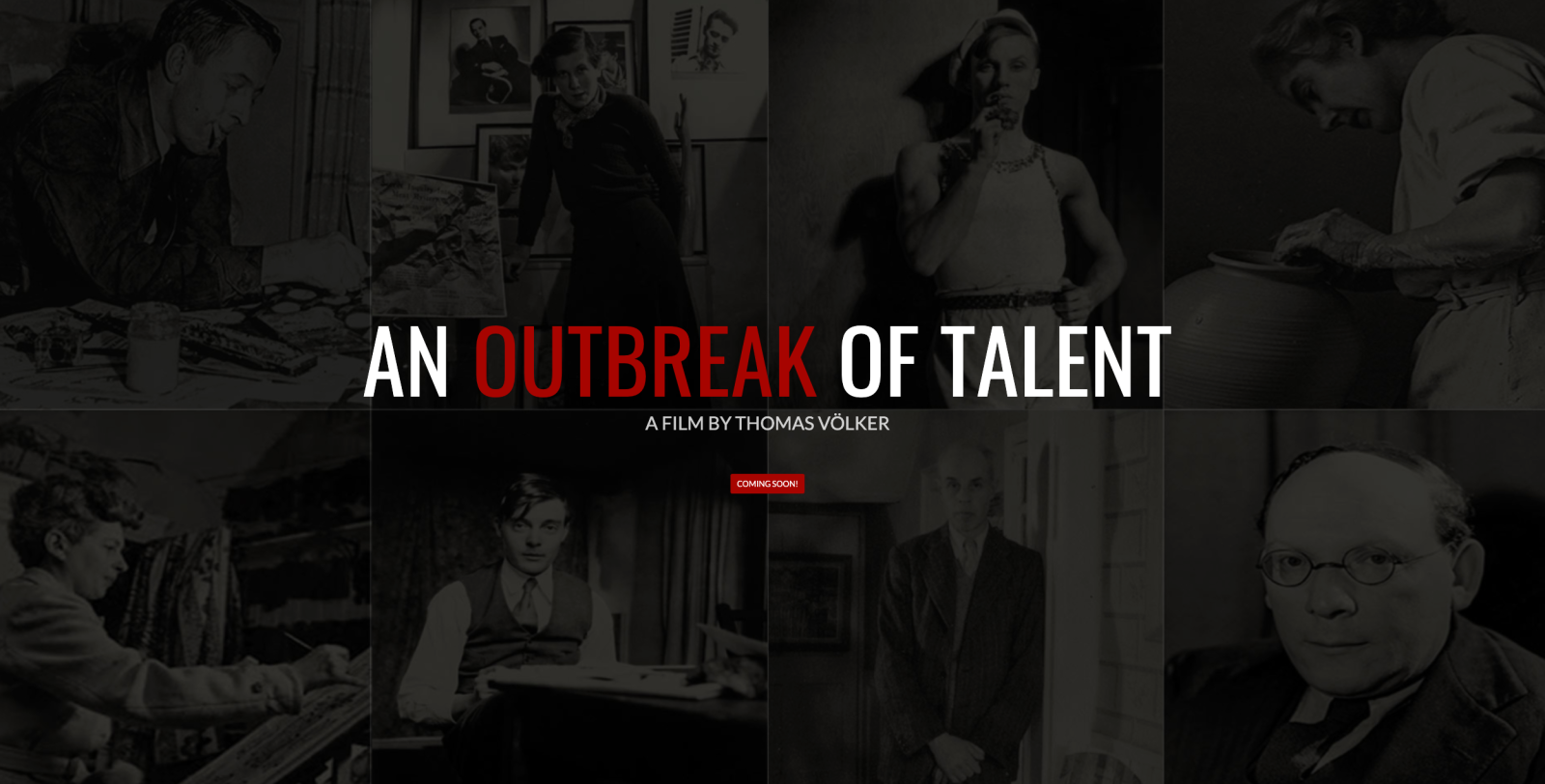

Nash's watercolours and his original approach to design made possible a generation of refined, intelligently constructed watercolour landscapes. For nine months between 1924 and 1925, he was a tutor at the Royal College of Art where he taught artists including Edward Bawden and Eric Ravilious. Other work such as the late watercolours of Edward Burra also adapted Nash's art. Writing in 1935, he described 'an outbreak of talent' at the Royal College which coincided with his time there - a phrase which has been seized upon in recent years by scholars and curators. In 2019, a symposium about this 'outbreak' was organised by the Fry Art Gallery, at the same time a related series of interviews was prepared by the filmmaker Thomas Völker, and, in 2020, Pallant House Gallery held an exhibition called An Outbreak of Talent with a focus on Bawden, Ravilious and Enid Marx.

A stylistic lineage ties Nash together with Ravilious and his peers, and this lineage is underpinned by a shared technique. The basic components of this were a heavy sheet of paper; an elementary outline of the composition in pencil, emphasising the formal structure of a lane, a hill, a furrow; and a dry-brush application of watercolour, making a minimal use of washes and laid in with extended strokes. Localised areas of hatching in some of Nash's works, including Spring Landscape, were subsequently extrapolated in the practice of Bawden and Ravilious, which made a more sustained, decorative use of hatching and cross-hatching. Beyond technique, Nash and his admirers shared a belief in the pictorial possibilities of the English landscape, and they exploited its nuances to great visual effect.