After a period living in Paris in 1931, Glyn Philpot changed his style. As a friend said, the new style was his attempt ‘to achieve a kind of bridge between the classic tradition which he loved and the new thought in art.’

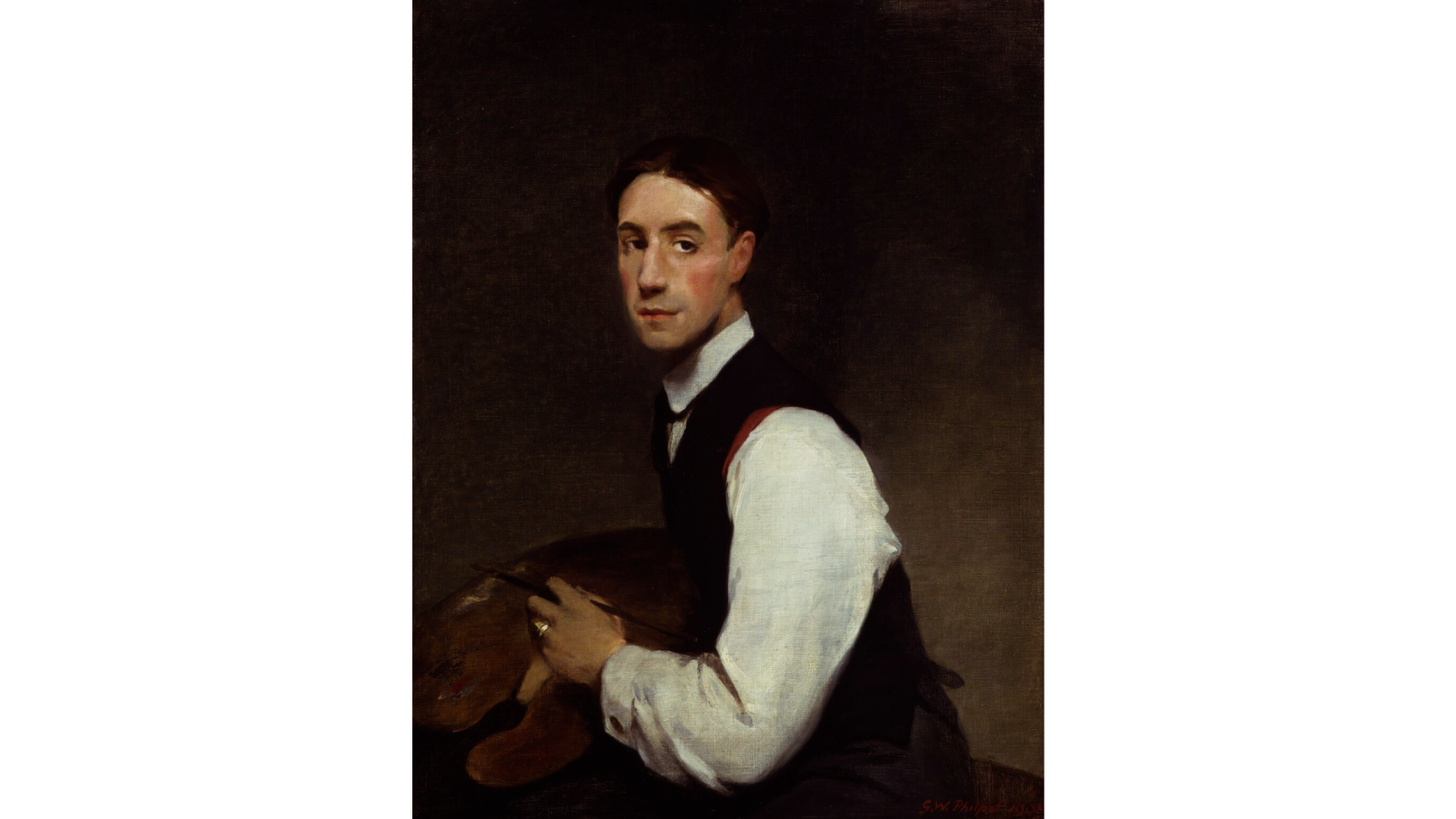

To begin with, Glyn Philpot (1884–1937) was a stylish young painter in the mould of Manet and Velázquez. His studio was on Tite Street in fashionable Chelsea from 1912 until 1923 and at that time his name was uttered in the same breath as Augustus John, John Lavery, Ambrose McEvoy and William Orpen – artist celebrities of the moment. At that stage in his career, Philpot was a painter of stylish society portraits with a conformist outlook. As his friend Gerald Heard suggested, ‘Cambridge and Bloomsbury had made a kind of alliance against the Royal Academy, Chelsea and the traditionalists’, and Philpot was unmistakably on the Chelsea side of this division.

After a period living in Paris in 1931, Philpot’s style changed markedly. He had already begun to make alterations in his palette and subject-matter at the end of the 1920s, but only after his return to England did the new style emerge more completely. The break is one of the more interesting examples of a decisive, self-conscious change of idiom in the history of twentieth-century British art, with the artist discarding his slick, smoothly-brushed surfaces and naturalistic colouring in preference of shimmering broken brushwork, a brighter and cooler palette, and firmer, more visible outlines. Philpot’s new idiom developed certain hints from the eclectic work of his ill-fated junior, the painter Christopher Wood (1901–1930). The restricted palette, the ambivalent sexuality of nude figures, the decorative floral sprays, and even mythological subject-matter were all found in Wood’s work before Philpot developed his own use for these things.

Though he had treated narrative figure subjects before, more amorphously classical and poetic subjects emerged in Philpot’s work of the 1930s, apparently as a complement to his new modernist idiom. Two Muses at the Tomb of the Poet, executed shortly before his death in 1937, co-exists in Philpot’s late mytho-modernist work with a motley cast of other Muses, mermaids, the Fates, St Sebastian, and many other blank-eyed, pensive, sallow-skinned gods and demigods. It was executed following a stay in the Riviera resort of La Trayas, the landscape of which appears in this work and related oils and watercolours from the visit. These impassive figures defy formal iconography, with Philpot instead using them to evoke a subtle atmosphere of melancholy and introspection. In his most engaging society portraits of this time, including Lady Gwendoline Cleaver and Lady Gwen Melchett among them, the sitter might be mistaken for one of these other-worldly mythic figures.

A significant aspect of Philpot’s work in the 1930s was interior decoration and his easel paintings register the period’s taste in luxury design. Among other projects, he executed designs for Lord and Lady Melchett’s drawing room in Mulberry House, Smith Square, and for the dining room of Sir Philip Sassoon’s new country house at Port Lympne in Kent. (The house is now run as a hotel, complete with a predictably named ‘Glyn Philpot bar’.) Gerald Heard recalled visiting him at work in Smith Square in 1930.

On arriving, I found he had the house to himself and was shown up to a very fine dining room. He was decorating it for a friend — all in what I have called his moonlight tone — silvers, greens and blues. One saw in the big designs he was sketching on the walls with that wonderful readiness of technique which he commanded, the beginning of his next effort — the attempt he made to achieve a kind of bridge between the classic tradition which he loved and the new thought in art. He did not, I knew, think he had succeeded, but nevertheless he felt that the effort was worth while.

Philpot has received growing attention in recent years. Scholarship has been advanced in part by Simon Martin, the director of Pallant House Gallery in Chichester, who completed his MA thesis at the Courtauld Institute in 2002 under the distinguished modernist scholar Christopher Green – his title was ‘Other Subjects: Ambiguity and Ambivalence in the Art of Glyn Philpot in the 1930s’. In 2016-17, Martin curated an exhibition called The Mythic Method, an overview of classicism in British art after the First World War which included Philpot’s work. He is currently working on a monograph about the artist to accompany an exhibition at Pallant House Gallery planned for 2022. In 2017, Brighton Museum & Art Gallery held a display dedicated to Philpot’s work, providing a succinct overview of the artist’s accomplishments. In an article for ArtUK at the time, the curators explained that the exhibition was part of the celebrations to mark fifty years since the decriminalisation of homosexuality. Only in recent decades has Philpot’s sexuality entered into the discourse around his work, providing a rich and under-explored topic for future scholarship.