Ivon Hitchens’s style was always highly individual. The free approach to colour and design in his later easel paintings developed in tandem with his work on large-scale murals in the 1950s and ‘60s.

Much of Hitchens’s (1893–1979) work was done outdoors. It is unclear when he began painting outside à la motif, but it became central to his working habits from 1940 onwards. In a recent essay about the artist, the curator Anne Goodchild narrated the momentous shift in his personal situation which threw him into the landscape and brought it within reach of his brush on a daily basis.

In 1940, Hitchens, his wife Mollie and baby son John left their bomb damaged London home for the sanctuary of Sussex. Through a combination of circumstances, he was able to acquire an area of woodland on Lavington Common near Petworth and – for £20 – a travellers' caravan in which the family lived and in which he painted.

As Hitchens himself noted in a letter from 1957, ‘Tho born in London, at a very early age I went to live among the silver birches and bracken and heather of Surrey, so that this area of Sussex has seemed homelike and familiar from the start.’ Though he later built a more permanent home nearby, the caravan remains in situ to this day.

Sussex Landscape was one of the last paintings that Hitchens made around his home in the plantation woods. The composition closely resembles that of another work made in the same year, Giant Oak Tree on Green Sky on Fields (1978, The Courtauld). Both paintings show an area of fields and sky opening out on the right-hand side. Just left of centre, a complex group of paint marks stands in for the eponymous ‘giant oak tree’: both works use a decisive downward arc from left to right, outlining its silhouette, with an amorphous inner structure variously suggesting the canopy and a trunk below.

Both these landscapes of 1978 are notable for their effervescent palette of contrasting, saturated colours. The use of purple, violet, green, blue and orange show Hitchens working away from the motif, rather than growing closer towards it as work progressed. Though there were always bright colours in his paintings, it was not until the early 1960s that the dominant tonality of Hitchens’s work developed from a low-key woodland palette in favour of loosely constructed sweeps of brighter greens, yellows and purples. The change reflected a shift in the prevailing winds in British art, from Neo-Romanticism in the late 1930s and ‘40s to large-format, Yankophile abstraction in the 1950s and ‘60s. But Hitchens’s style was always highly individual. Rather than a changing zeitgeist, the freer approach to colour and design in his easel paintings was more likely encouraged by large-scale murals which he undertook around this time, including those at Cecil Sharp House (1954), Nuffield College, Oxford (1959) and Sussex University (1963), which required an enhanced sense of scale, bolder design and less nuanced detailing.

Many painters in the twilight of their career experience frailty and a loss of technical facility (if not a loss of creative vision). The reputations of many such artists are sustained by their earlier work. Ivon Hitchens is a rare example of an artist whose late fame was accompanied by technical consistency. Works executed in the last years of his life are often indistinguishable from those made twenty years earlier. The sustained quality of his output was matched by continuing accolades and in the last two years of his life, in 1978 and 1979, he was the subject of two retrospective exhibitions (one travelling from the Towner Gallery, Eastbourne, to the Mappin Art Gallery, Sheffield, and the other at the Royal Academy).

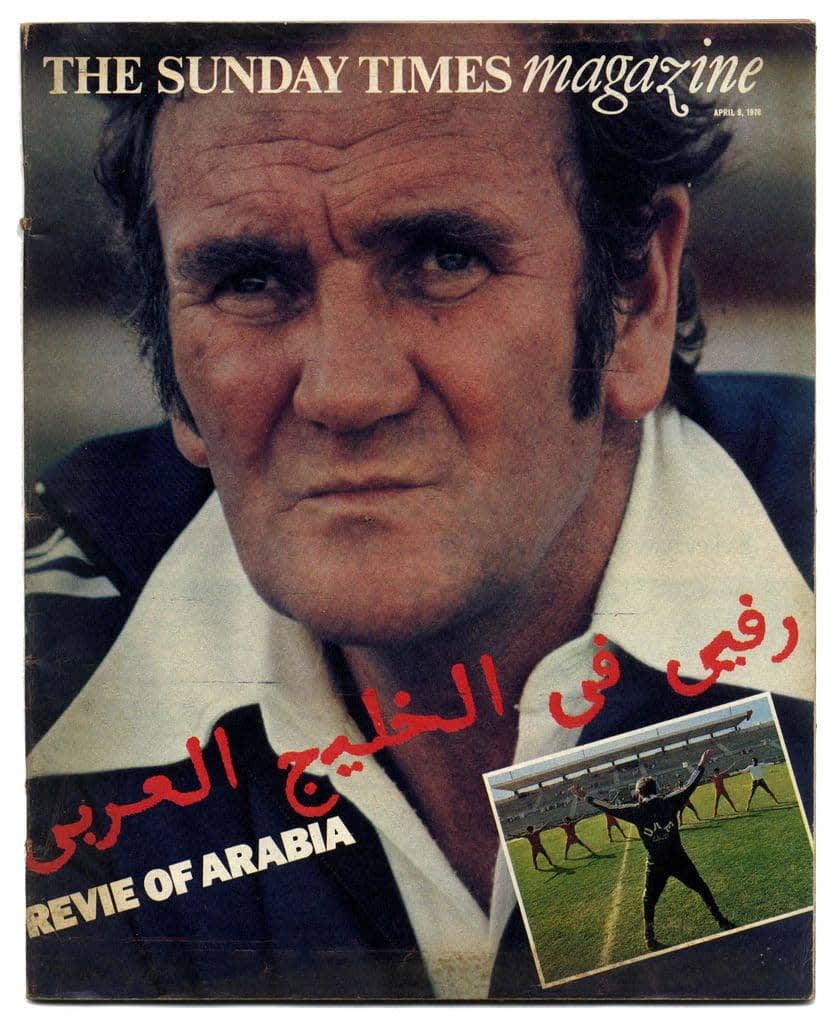

The point about Hitchens’s consistency was made by his fellow painter Lawrence Gowing, who authored a piece for The Sunday Times Magazine in April 1978 shortly before this flush of exhibitions. The editorial referred to Hitchens ‘whose work, at the age of 85, remains as fresh as the Sussex country-side in which he lives and paints.’ It is noteworthy that some decades previously, in 1947, Gowing had painted a woodland scene near Petworth not dissimilar from those being made by Hitchens at the time. Gowing was twenty-five years Hitchens’s junior and it is unclear whether or not they knew one another at the time.

Like a baton being passed from one runner to the next in a relay race, Hitchens’s style had an effect on later British artists working in a painterly manner. Shortly after Hitchens’s death in 1979, Howard Hodgkin began using more gestural brushwork and compositions organised around singular sweeps of paint. Though his practice differed in many respects from Hitchens’s, the freeform relationship between a brushstroke and its representational connotations (of enclosed space, glimpsed bodies of water, etc.) is a significant continuity from the older to the younger artist. Aside from his longevity, his consistency and his individuality, it is lineage like this which justifies the enduring critical approbation which Hitchens and his work continue to enjoy.