In a special edition of InSight, Sam Cornish considers the ‘pillars of space’ in John Hoyland’s work from the 1960s. Cornish is a leading specialist on Hoyland and is co-editor of the forthcoming catalogue raisonné of Hoyland’s paintings.

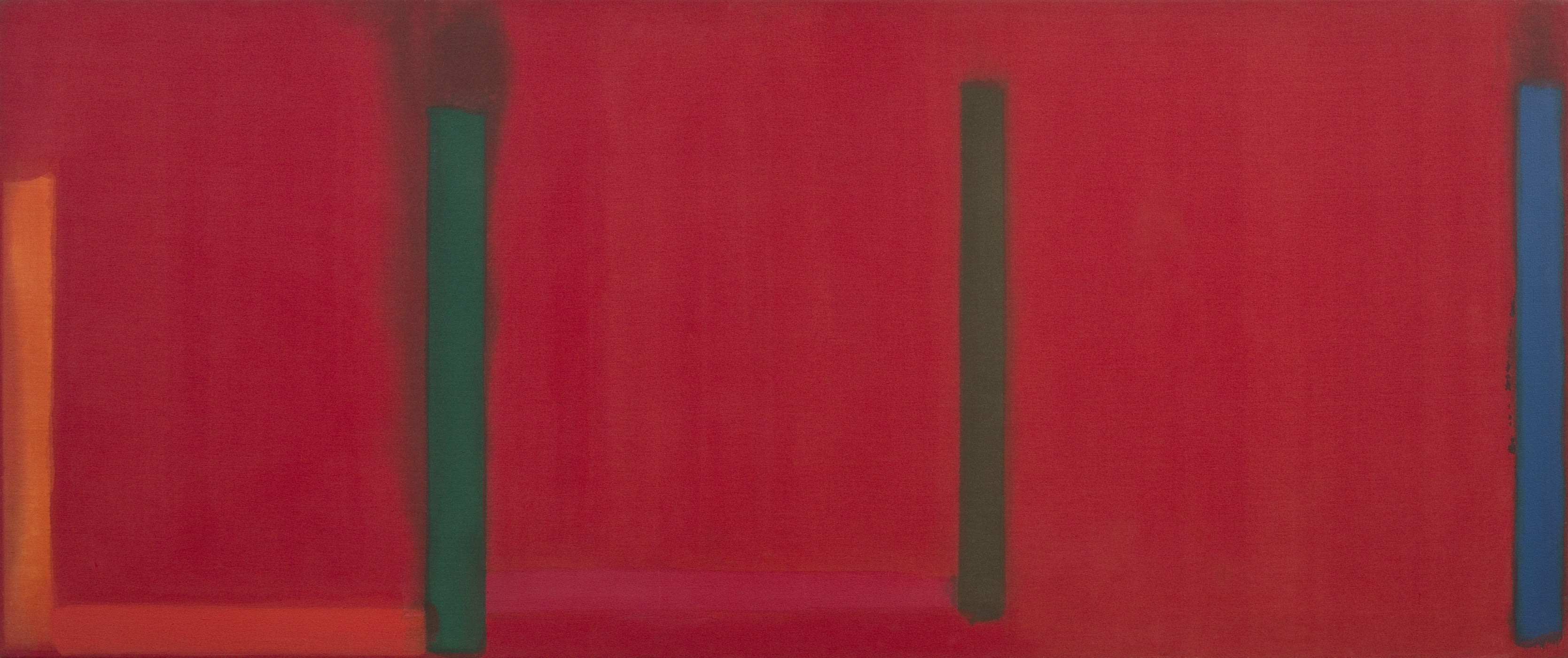

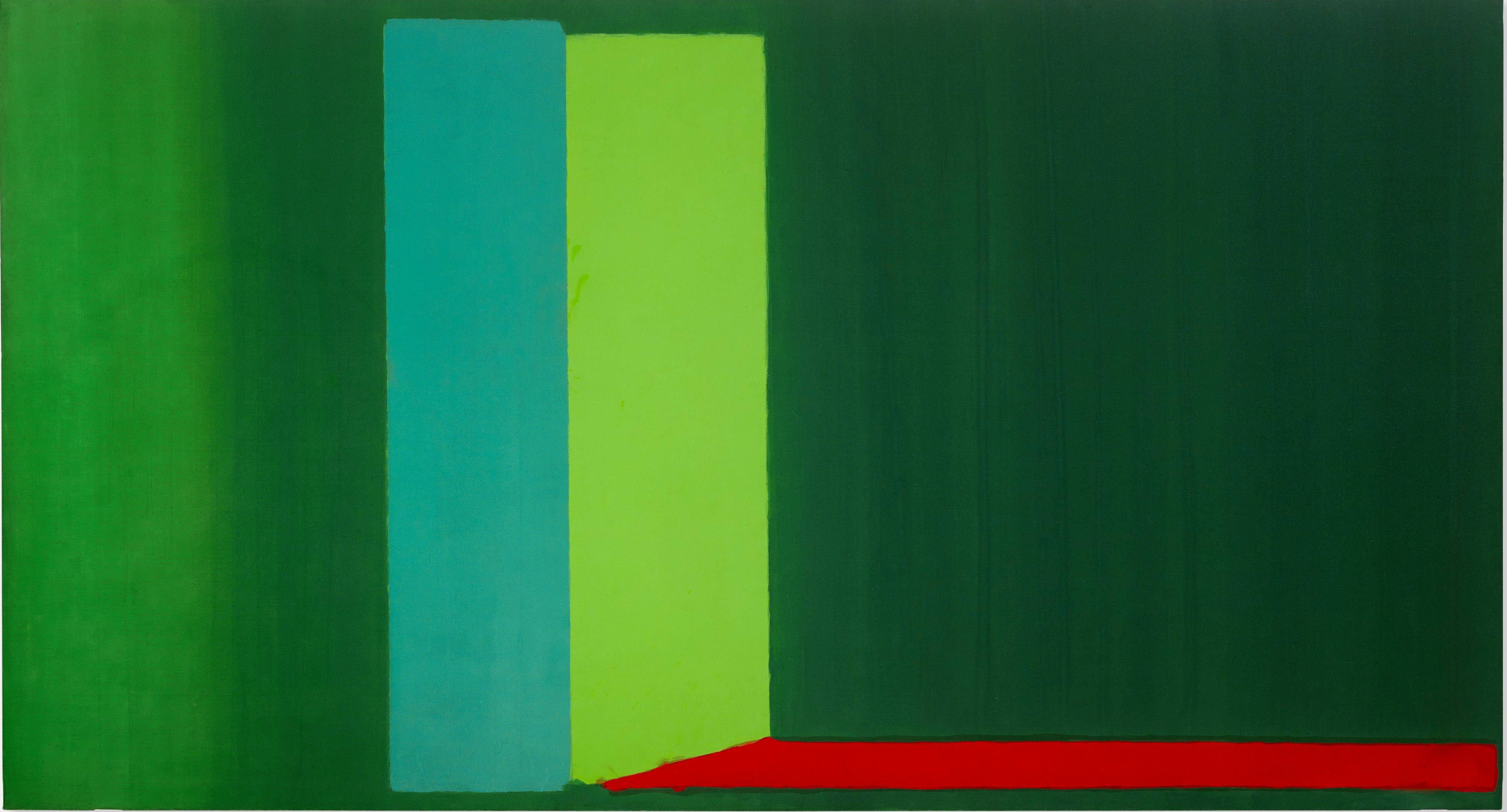

John Hoyland’s 16.9.66 presents us with an image of an ideal, unworldly architecture, remote yet vividly present. Its horizontals and verticals could be seen as purely abstract elements – perhaps resembling a hugely expanded and partially disassembled Mondrian painting. Yet they also suggest the beams and columns of some impossible edifice, whose substance appears at once solid and almost as immaterial as the large red expanse it is set against. This evocation of architectural structures was a central part of Hoyland’s paintings in the second half of the 1960s, the years in which he first fully established a powerful and personal style.

In our everyday experience, architecture becomes temporal as we move through it. By contrast, in 16.9.66 and many of the paintings related to it, duration seems a property of the architecture itself. Do the haloes that flare around the columns imply a dissolution or a coming into being; or an on-going unfurling, like a smoking chimney or material dissolving in a test-tube? Perhaps they register the blur of movement, as if these beams and columns had just found their positions, and so could shift again. It is part of Hoyland’s sophistication that we can potentially answer ‘yes’ to all these questions, even as the image as a whole retains an unambiguous clarity.

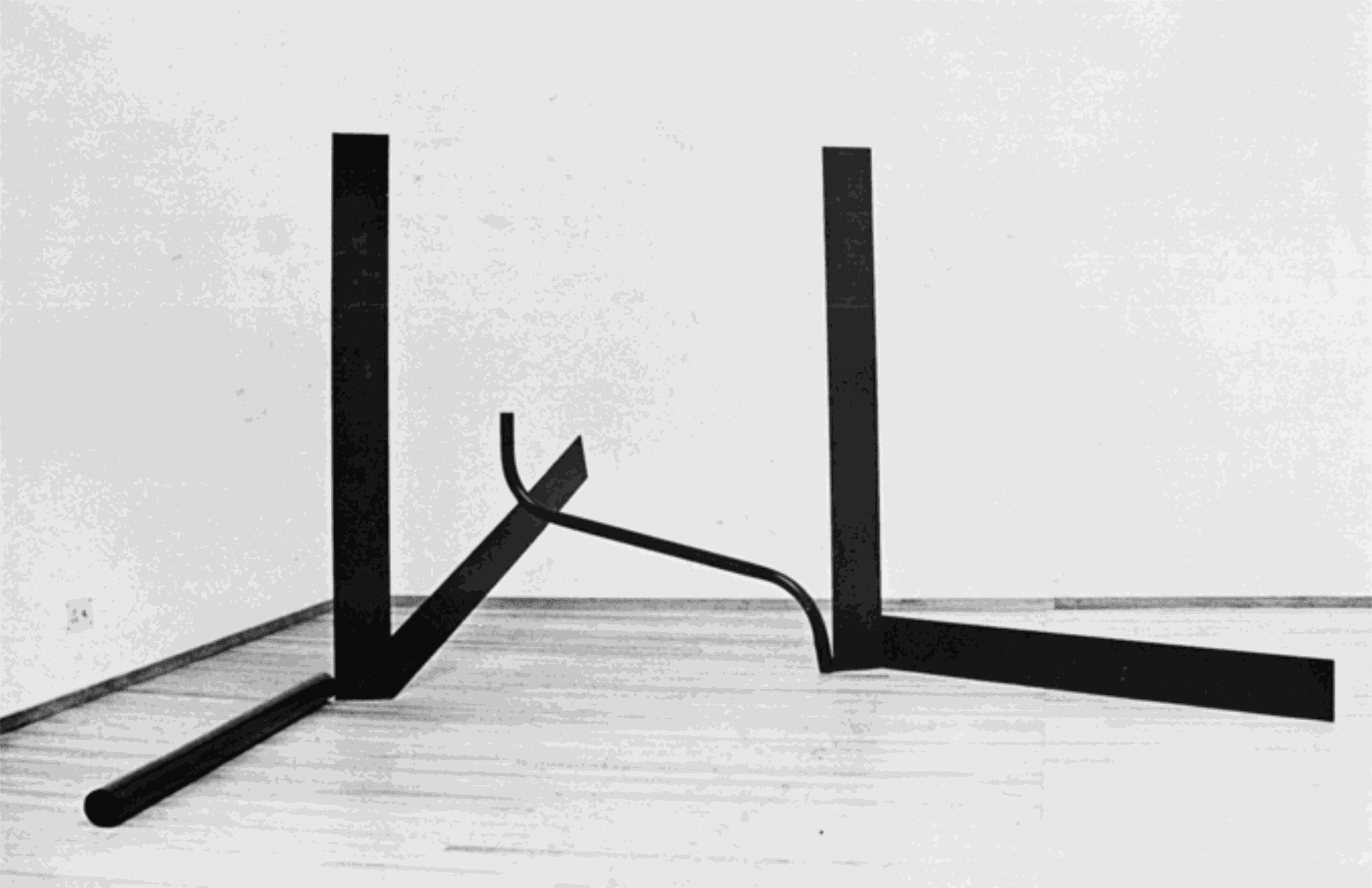

16.9.66 was completed a few weeks before Hoyland’s thirty-second birthday. He was a self-confident, ambitious and hard-working young artist. The following spring, an early career retrospective of his paintings from 1960 to 1967 was put on display by the Whitechapel Art Gallery – only his third solo exhibition. Such was his productivity that curator Bryan Robertson re-hung the whole display halfway through the run. The Whitechapel show positioned Hoyland as a force to be reckoned with, both nationally and internationally, and in the next three years he held more than a dozen solo exhibitions, in London, Los Angeles, New York, Munich, Montreal and Milan. In 1969, he represented Britain in the São Paulo Biennale alongside sculptor Anthony Caro.

An idealized architectural imagery became central to Hoyland’s paintings in the three years leading up to the Whitechapel exhibition. Invariably positioned within shallow-infinite fields of red or green, architectural structures appear in various guises, and at different degrees of directness. In some paintings, the columns of 16.9.66 expand into glowing walls or open doorways of colour, while others contain abbreviated hints of perspectival recession, forming arrangements suggestive of colonnades, opened thresholds or pathways – devices which were largely anathema to the abstract painters Hoyland measured himself against. The basic combination of beam and column in 16.9.66 occurs in around ten paintings made from April 1966 until July 1967, including in works now held by the Arts Council Collection, the Art Gallery of South Australia, the Yale Center for British Art, and Damien Hirst’s Murderme collection. 16.9.66 is the smallest of this group, one of only a few of reasonably domestic size, with most of the others spanning ten or twelve feet.

At that moment, Hoyland was a profoundly transatlantic artist. His central focus was recent large-scale, emotionally driven American painting – both abstract expressionism and its cooler, less angst-ridden successor in post-painterly abstraction. He first visited New York in 1964 and subsequently lived and worked in the USA for extended periods until the early 1970s. The enveloping scale and architectural intimations of paintings by Barnett Newman and Mark Rothko are important precursors, as is what Hoyland called the ‘dream space’ of Morris Louis’s images.

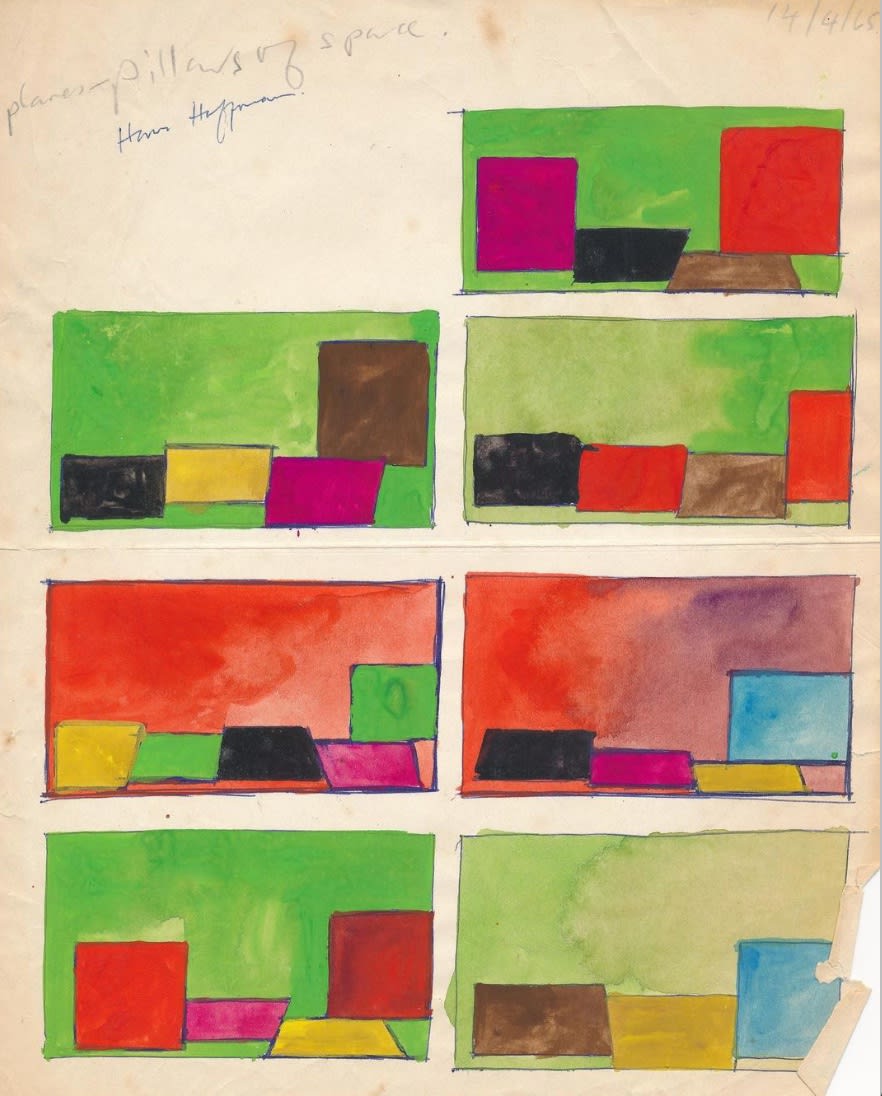

A counterweight to American influence was the sculpture of Caro and his peers such as William Tucker. It is perhaps due to contact with their work that Hoyland was willing to give his shapes a sense of solidity and explicit groundedness, not found in otherwise comparable American painting. Most vital was the example provided by the planes in the late paintings of German-American painter Hans Hofmann, first acknowledged by Hoyland in a quotation on a sheet of watercolour studies in 1965 “planes – pillars of space.’

Though architecture was a crucial term in Hofmann’s vocabulary, Hoyland’s employment of it was very different. For Hofmann, architecture was an over-arching structural aspiration, signifying a fully-achieved, vital and plastic pictorial equivalent to our experience of the breadth and depth of the world. Hoyland’s concept of ‘architecture’ is at once more literal or more symbolic, in its evocation of beams, columns, walls, colonnades, pathways or thresholds; and more abstract, in the more generalised and purified space in which he placed these architectural elements.

Of all the American artists Hoyland met, it was Robert Motherwell with whom he struck up the closest friendship, which lasted until Motherwell’s death in 1991. Intriguingly, Hoyland’s idealized architectures just precede Motherwell’s important ‘Open’ series, which, although different in many ways, contain a closely related amalgam of architectural elements and purified abstract space. Motherwell’s series has been related to a wide variety of precedents in modernist painting, some of which are also relevant to Hoyland, such as Matisse’s famous Window at Collioure (1914). The ‘Open’ series show Motherwell responding to the simplified forms and more restrained emotion explored by many younger artists from the later 1950s and through the 1960s. Could Hoyland’s architectural images have provided a specific stimulus to the older artist’s imagination?