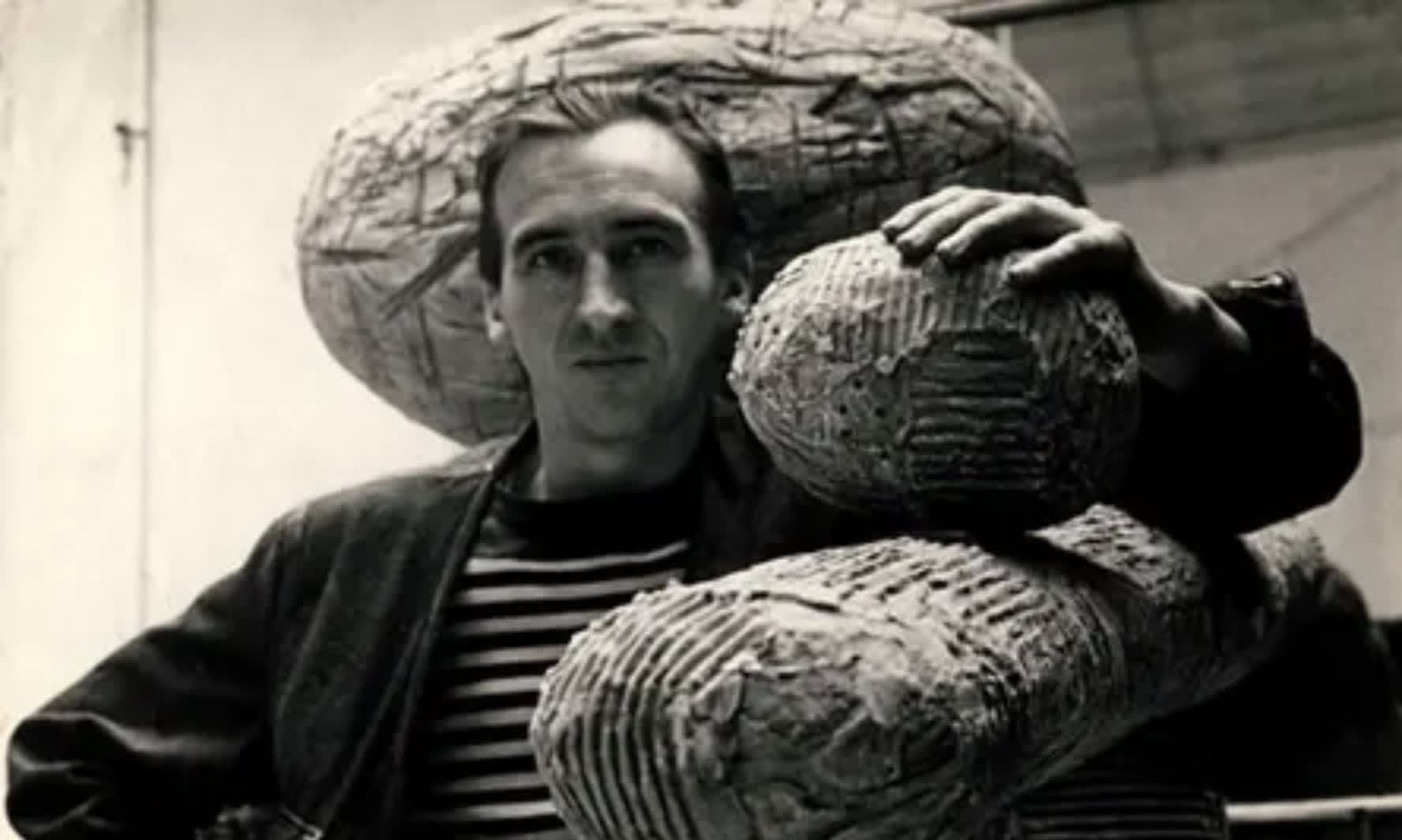

The Scottish artist William Turnbull went between tachiste Paris and colour field New York, and devised a versatile succession of paintings and sculptures that range from muscular gesturalism to matte subtlety.

Many artists in the history of Western art have developed skills in several different media, combining draughtsmanship and painting, painting and printmaking, printmaking and stage design, and so on. Only rarely, however, have artists defined themselves by their work in more than one media: Sickert and Morandi were painters, who also made etchings; Barbara Hepworth was a sculptor, who also made drawings. As an artist who is known and admired equally for his paintings and his sculptures, William Turnbull (1922-2012) is a rarity.

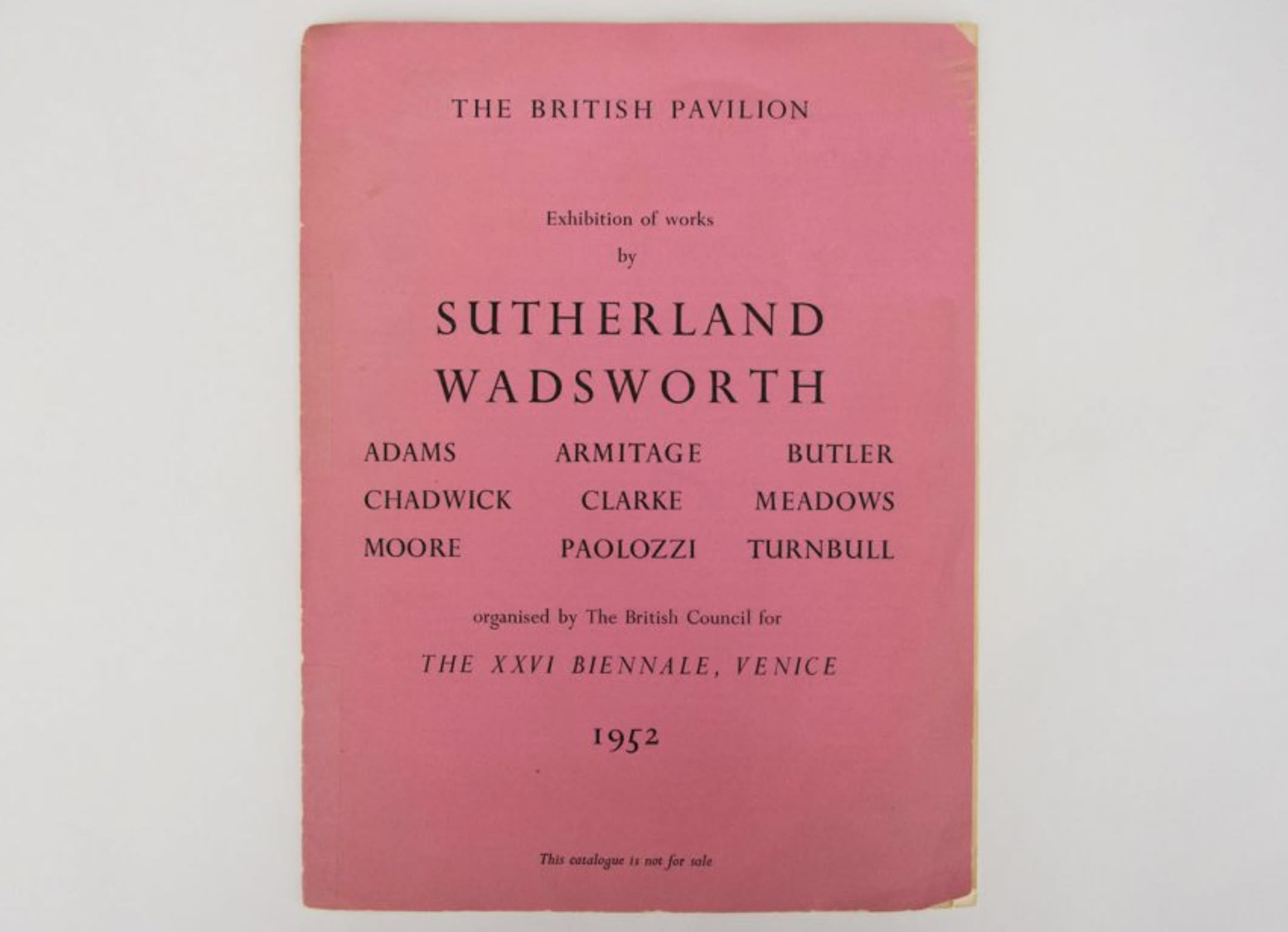

The highlights of Turnbull’s career include a friendship with Giacometti in Paris in the late 1940s, an initial exhibition at the Hanover Gallery in 1950 (held the same year and in the same place as the first solo show of his exact contemporary Lucian Freud), inclusion in the 1952 Venice Biennale where Herbert Read coined the ‘geometry of fear’ label, membership of the Yankophile Situation Group, association with the St Martin’s-based ‘New Generation’ sculptors, and his portentous introduction of Anthony Caro to the American critic Clement Greenberg in 1959. It was a busy life, full of travel and connections.

Turnbull was rare among British artists for the degree of success which he enjoyed with American collectors from the later 1950s. He ventured there for the first time in 1958 and was awarded his first solo exhibition in New York at Marlborough-Gerson Gallery in 1963. Shortly after this his unique bronze-and-stone totem, Hero II, was acquired by Marcia Weisman to adorn her Los Angeles poolside.

Turnbull was not only admired in the US by patrons of the arts. David Hockney was sufficiently interested by Hero II to include it in the portrait of Weisman and her husband, Fred, which he painted in 1968. The painting was called American Collectors. It plays with the scorching midday sunlight, composing the Weismans and Turnbull’s sculpture so that their short shadows intersect orthogonally with the grid of receding flagstones. Nearby is an American Indian totem pole, lurking flatly on the right-hand edge of Hockney’s painting. In this context, Turnbull’s work becomes an instrument for ‘ceremonies as yet unformulated’, contributing to the vague sense of ritual which pervades American Collectors.

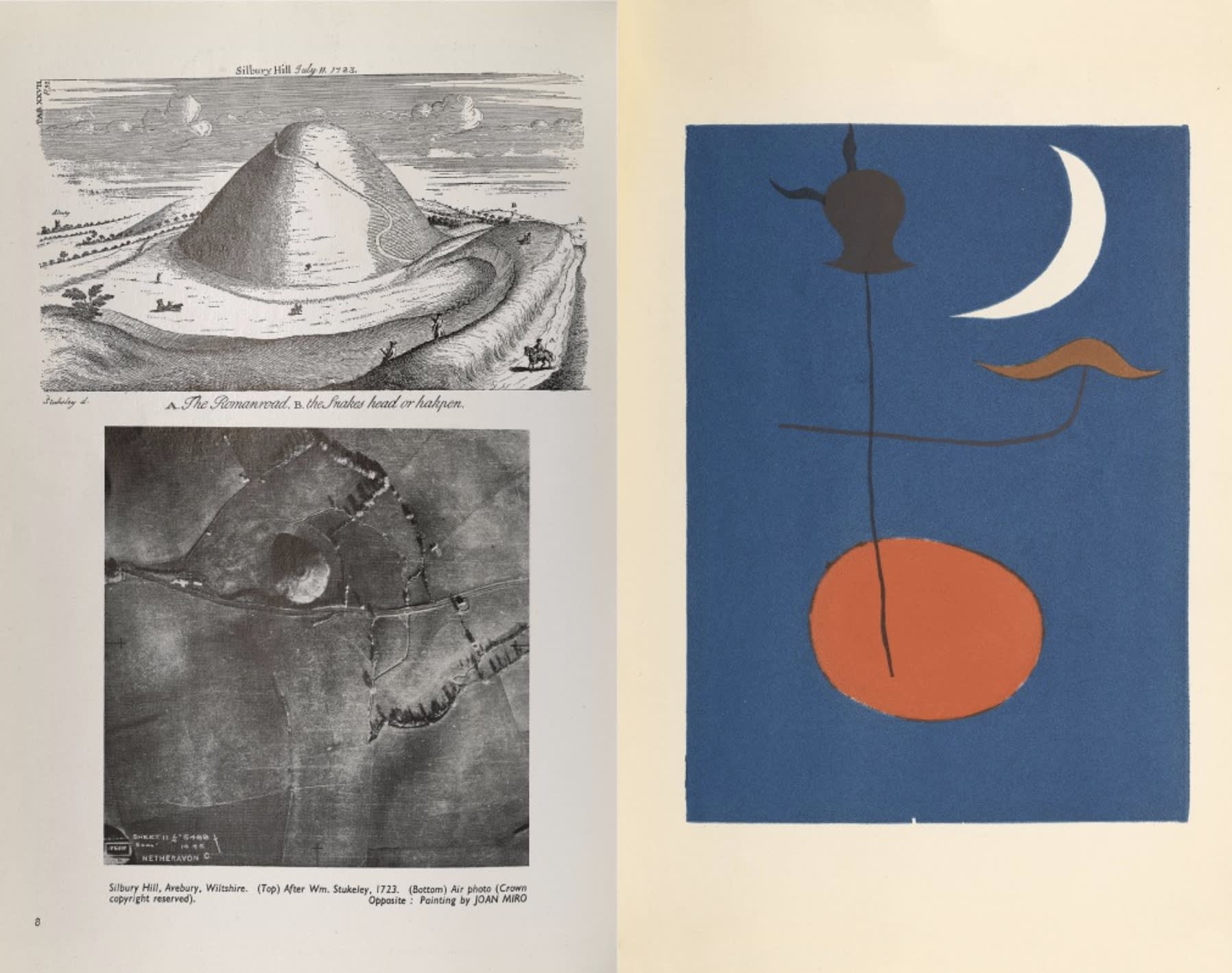

Turnbull’s stripe paintings like 1-1965 partly derive from his flying experience with the Royal Air Force during the Second World War. There had been a growing interest in aerial photography in the 1930s, taken up by archaeologists and (briefly) by the artist John Piper, who pointed out in the modernist magazine Axis that some of Joan Miró’s paintings looked like a landscape viewed from above. Later, in the early 1960s, Turnbull travelled to Singapore and became fascinated by the airborne view of rivers snaking through dense tropical forests. Though he was disinclined to explore any particular landscape in his art, the aerial perspective nevertheless prompted a new way of organising the canvas and the experience informed his abstract work of the period.

Writing in Private View in 1965, the art critic John Russell explained the origins of Turnbull’s abstract paintings.

Never really suited to the restricted dimensions and general cosiness of old-style English art, [Turnbull] took immediately to the huge-scale and tyrannical absoluteness of Barnett Newman […]. The canvases of Turnbull’s in which an enormous unbroken field of colour is broken only by a narrow slanting diagonal are not well known – few London galleries could house them anyway – but they constitute a majestic act of homage to the New York School.

Since then Turnbull’s paintings have grown in recognition, and even before Russell wrote these words, in 1963 Turnbull began deviating from Newman’s example by introducing a wending, non-linear stripe like that seen in 1-1965. Casting off his New York School precursors, Turnbull brought his own intentions to the format of large-scale abstract painting: ‘I suppose I want to work by a sort of colour saturation, and to cover as large a part of the wall as possible.’ In works like 1-1965, these intentions were fully realised.