In the nineteenth century, almost all sculptors used clay to model their work; assistants then transferred the model into a scaled-up version in bronze or stone. When Eric Gill started using direct stone carving in 1909, it transformed the way people thought about sculpture.

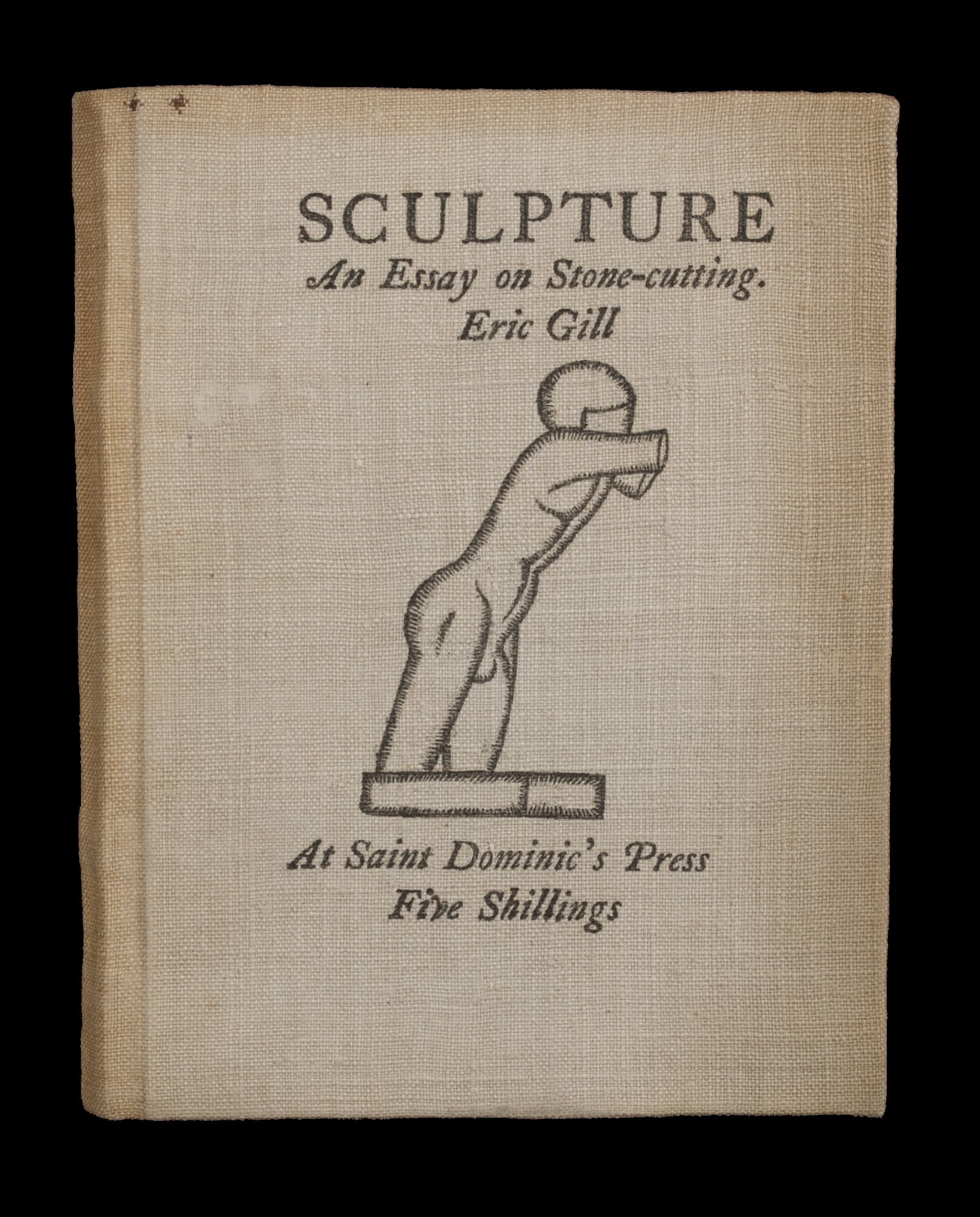

Gill (1882-1940) regarded himself as both a craftsman and a philosopher. Considering the licked finish which had dominated painting and sculpture at Royal Academy exhibitions since the middle decades of Victoria’s reign, it unsurprisingly took more than just craft skills to overthrow a generationally embedded aesthetic – it also required argument. In Sculpture: An Essay on Stone-Cutting, published in 1923 by a private publishing entity he had co-founded, St Dominic’s Press, Gill wrote that ‘[t]he sculptor's job is making out of stone things seen in the mind.’ His aphoristic writing style was marked by the sequential assertion of artistic principles, and his strong belief in the connection between beauty and moral goodness instilled him with a charismatic sense of rightness in his arguments as well as in his art.

Despite the highly principled approach to art which he adopted in his writings, in practice Gill’s work drew upon a variety of sources. ‘Primitivism’, the unsympathetic adaptation of ‘other’ cultures for artistic purposes, was particularly widespread in early-twentieth-century Europe. Keystones of this amorphous trend were Picasso’s use of African tribal masks in Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907, MoMA) and Henri Matisse’s painting The Dance (1910, Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg), which depicted a troupe of naked red figures in a sinuous, Bacchic composition. Though not in direct lineage to either of those works, Gill’s relief carving of 1913, Boxers, nevertheless draws upon similar motifs: dynamic interlocking movements of the naked human body and ethnically ambiguous figure types.

A further salient connection between Boxers and The Dance is the colouring of the figures’ skin. Where Matisse depicted the dancers in a uniform red hue, Gill’s two figures were at one time coloured in brilliant, unmodulated hues of red and yellow. (After exhibiting the work at the Goupil Gallery in January 1914, he added colour to the figures in February or March that year, but subsequently removed this, while leaving untouched the figures' black hair and the green and blue architectural surround.) In these significant works of modernist primitivism, colour held a semantic value, helping to signal the avant garde ‘otherness’ of this art. Alongside these values, however, Boxers also follows certain Western traditions. The sculptural block as a whole is modelled as a metope, a type of relief carving which originally adorned the friezes of Greek temples. This connotation is only underlined by a simple classicising framework of plain pilasters to mark the left and right edges.

Boxers was initially commissioned from Gill by Count Harry Kessler, an Anglo-German man of culture and a patron of modern art. He never took possession of the work, however, and it remained in Gill’s studio until 1915. At that time, it was purchased from the artist by another of his patron friends, Geoffrey Keynes. Keynes made a number of visits to see Gill at Ditchling in 1912 and 1913, on one occasion visiting with the poet Rupert Brooke and later commissioning a Mother and Child subject from him. Gill addressed his letters to ‘my dear Keynes’ and borrowed Keynes’s Mother and Child carving for an exhibition at Goupil Gallery in 1914 – the very place where Keynes first saw Boxers.

Keynes acquired the work in April 1915 as a wedding gift for his friend, the dashing schoolmaster and expeditious mountaineer George Mallory. Mallory was working at Charterhouse at the time though he later became famous for his exploits to Everest which culminated in the death of him and his climbing partner Sandy Irvine in their attempt to summit the mountain in 1924. Boxers was subsequently returned to Keynes – a reminder of both his friend’s marital joy and his tragic demise.

Boxers stands at a crossroad in British art history. Gill’s advocacy for direct carving was hugely influential, and the likes of Jacob Epstein and Henry Moore later took heed of his technique, appropriating it for their own modernist ends. As well as pointing ahead to later sculptors’ reconfiguration of craft ideals, it belongs to a wider assimilation of the continental style of primitivism which was taking place in the early twentieth century, while its subject matter and architectural format connote the far older, classical ideals of ancient Greece. Boxers is an important early work in Gill’s artistic development, and all of these factors taken together suggest the originality of not only its style and conception, but more fundamentally, of its very making.