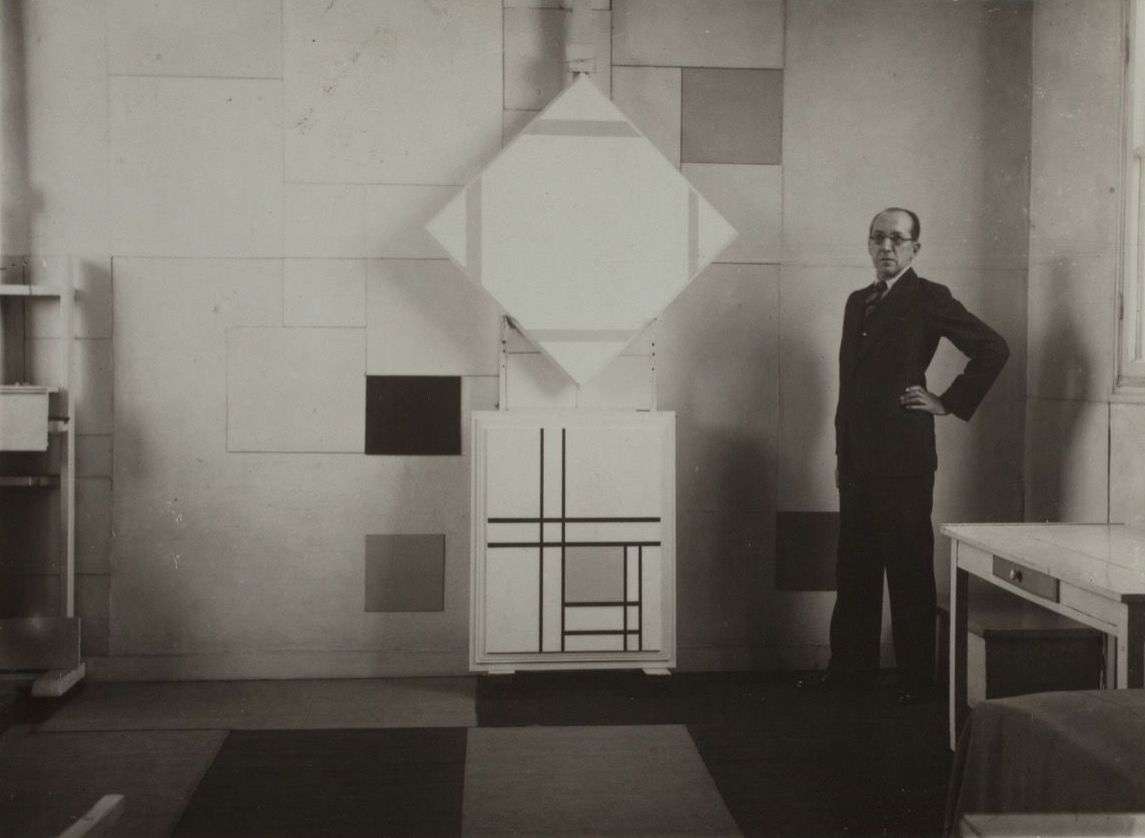

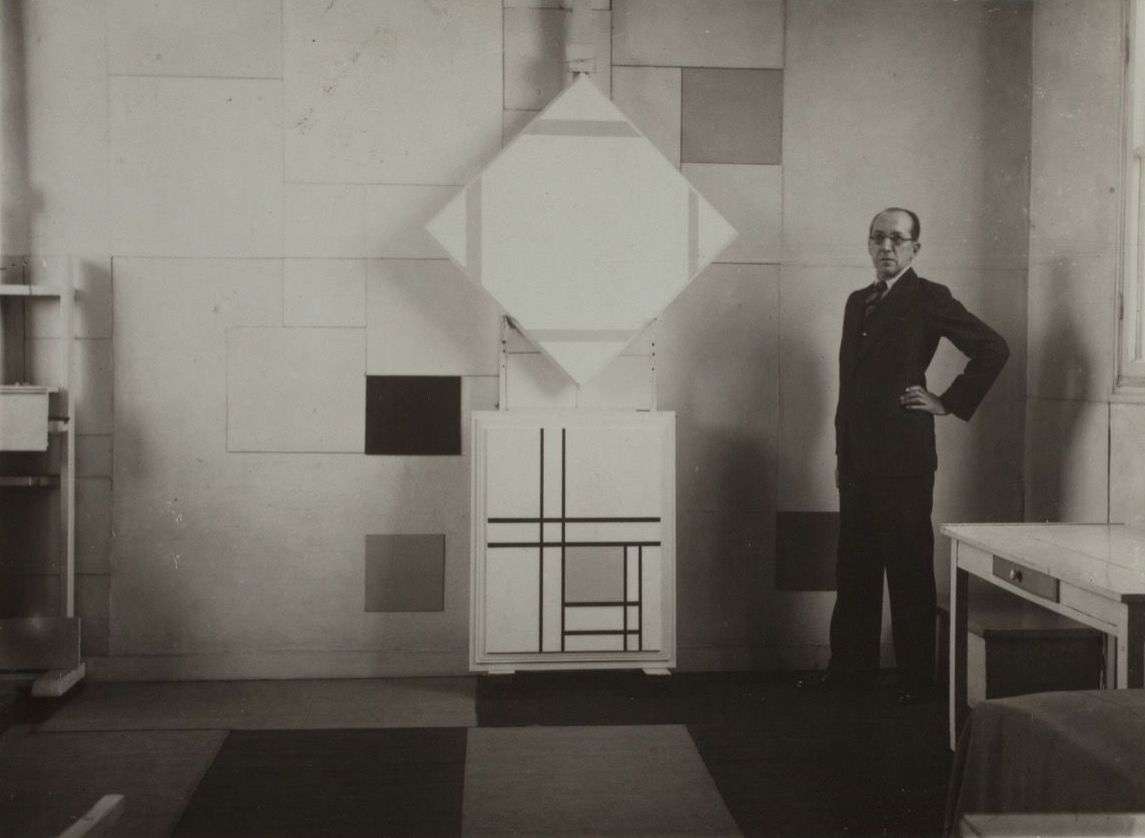

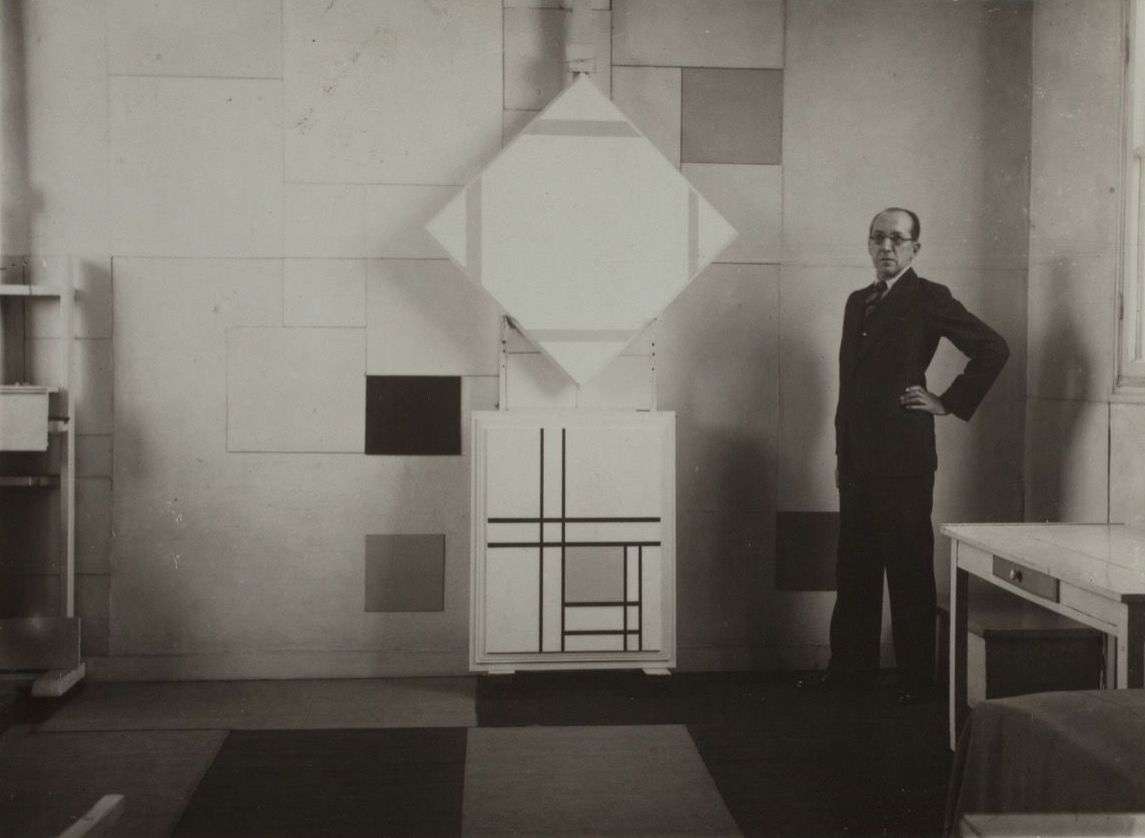

Alexander Calder began his career making humorous art, with wry drawings and playful wire sculptures of animals and acrobats. In 1930, however, after a visit to the studio of Piet Mondrian, his art started moving in another direction entirely.

InSight No. 20

Alexander Calder

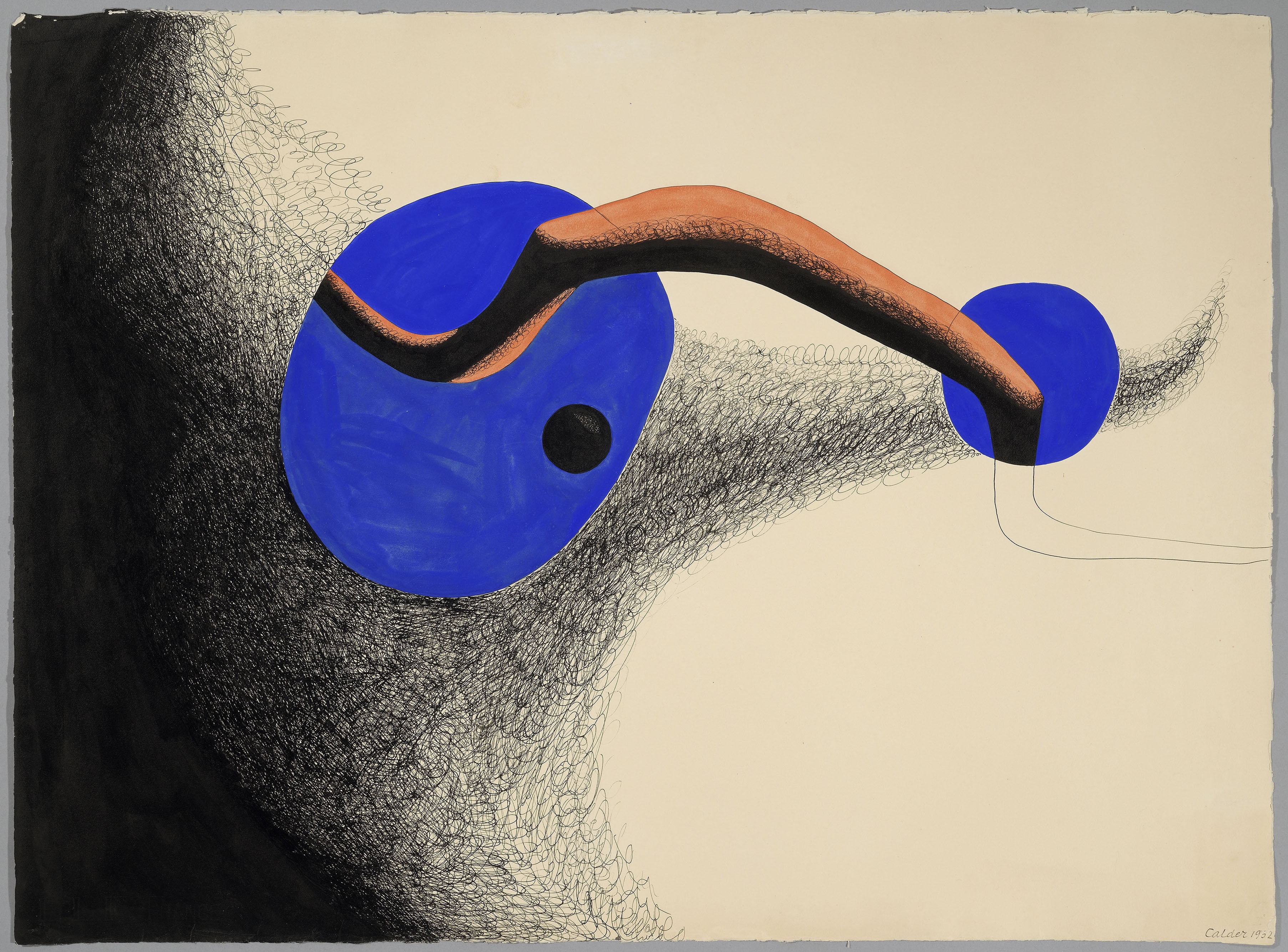

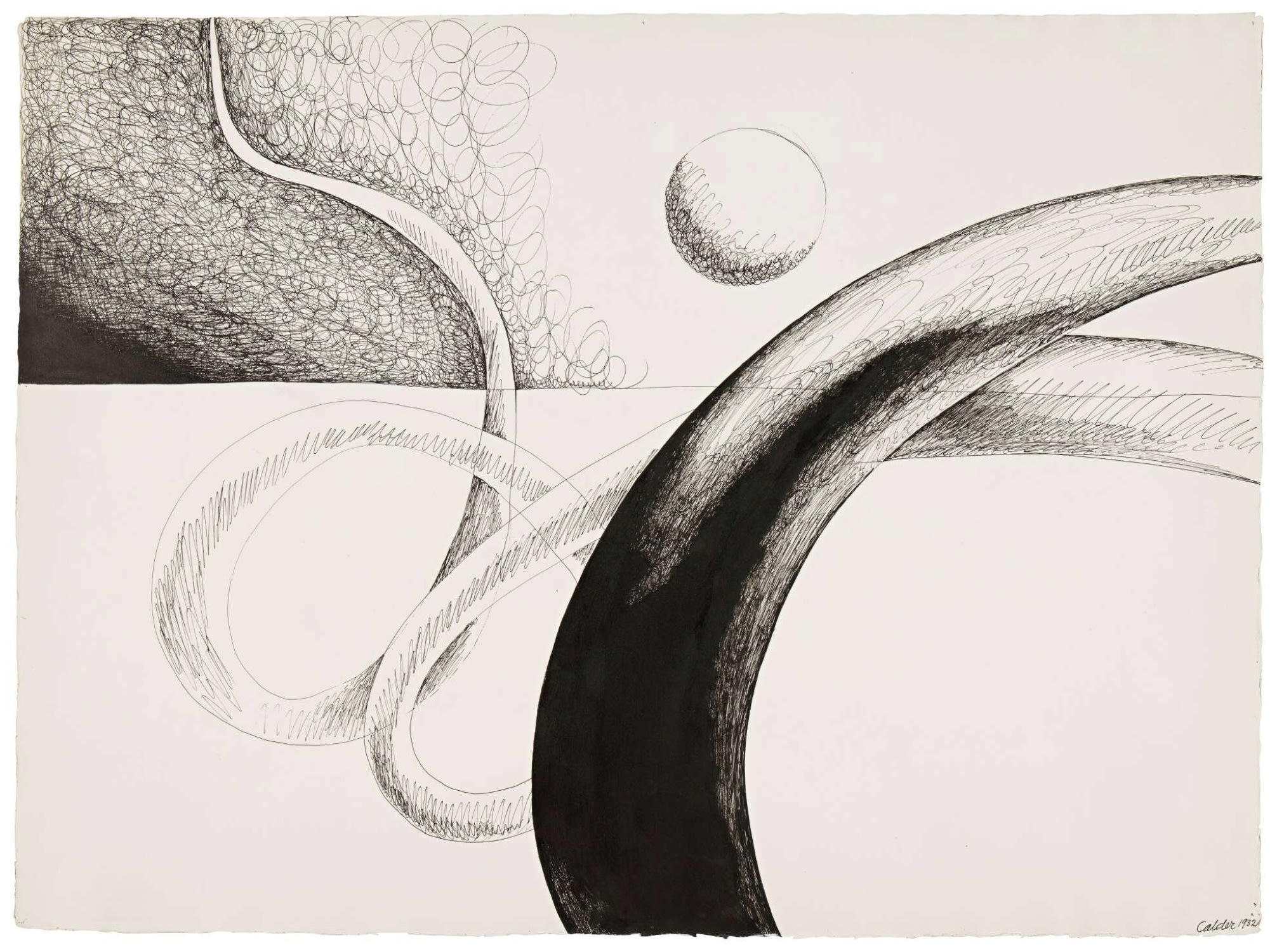

Untitled, 1932

Calder (1898-1976) later described his visit to Mondrian’s studio as ‘the necessary shock’. It introduced him not only to pulsating primary colours – the yellow, blue and red which became signatures of his work – but also to a new milieu: the members of a group called ‘Abstraction-Création’, who were in the avant-garde of abstract and surrealist art. It was in response to Mondrian and his new friends, Hans Arp, Théo van Doesburg and Jean Hélion, that Calder started making a more serious, less representational type of art.

It was an exciting time in Calder’s life. He had been criss-crossing the Atlantic since 1926, going between New York and Paris, holding exhibitions everywhere he went and generally winning acclaim. In 1931, he married Louisa James, great niece of the distinguished philosopher William James, and immediately afterwards they set off for Paris on SS American Farmer. The trip turned out to be one of the longest periods abroad, and he did not return to the United States until July 1933. It was a fruitful time during which he produced not only his first mobiles, the kinetic sculptures that give him a place in art history, but also a number of intense, surrealist-flavoured compositions on paper.

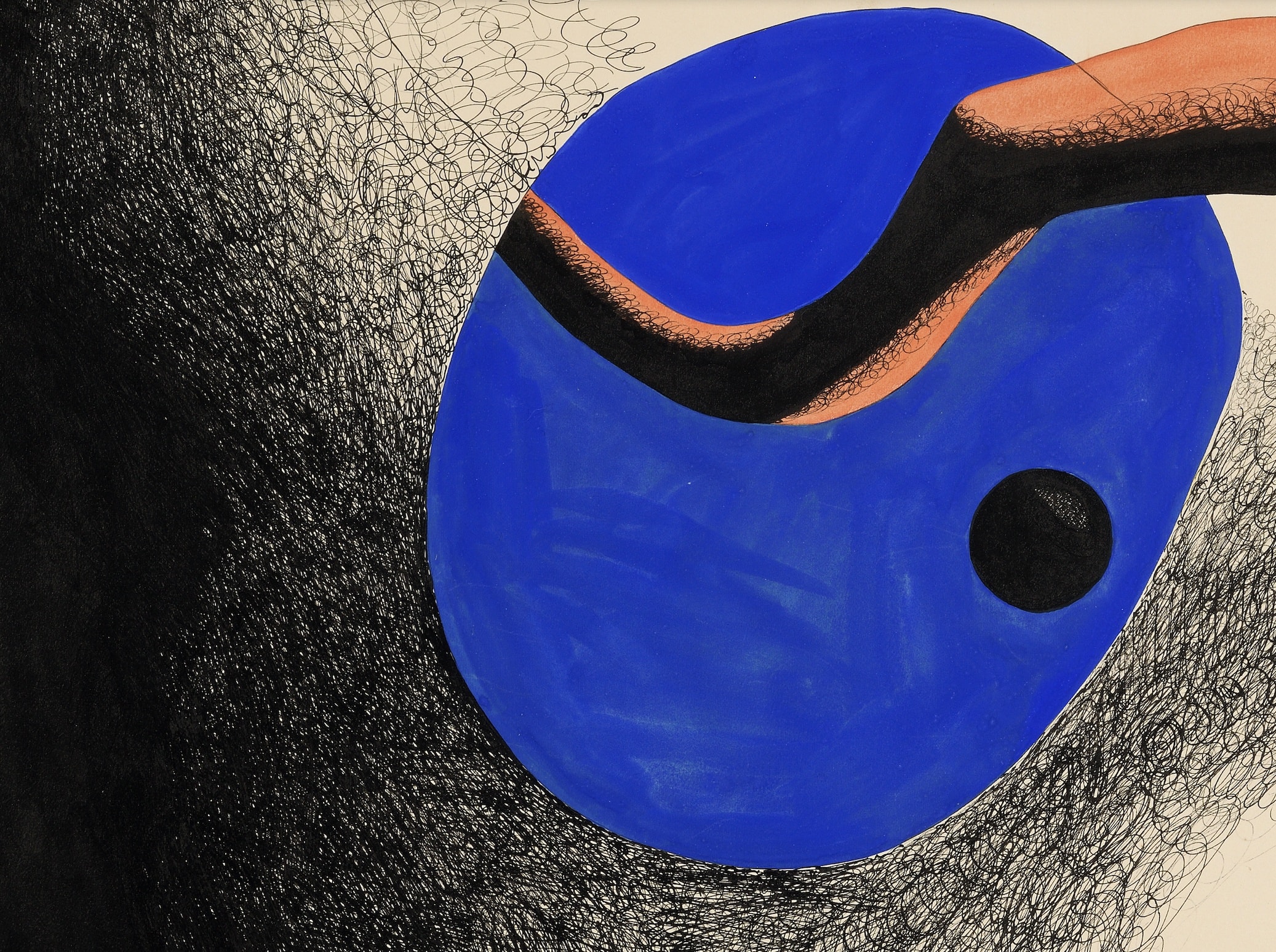

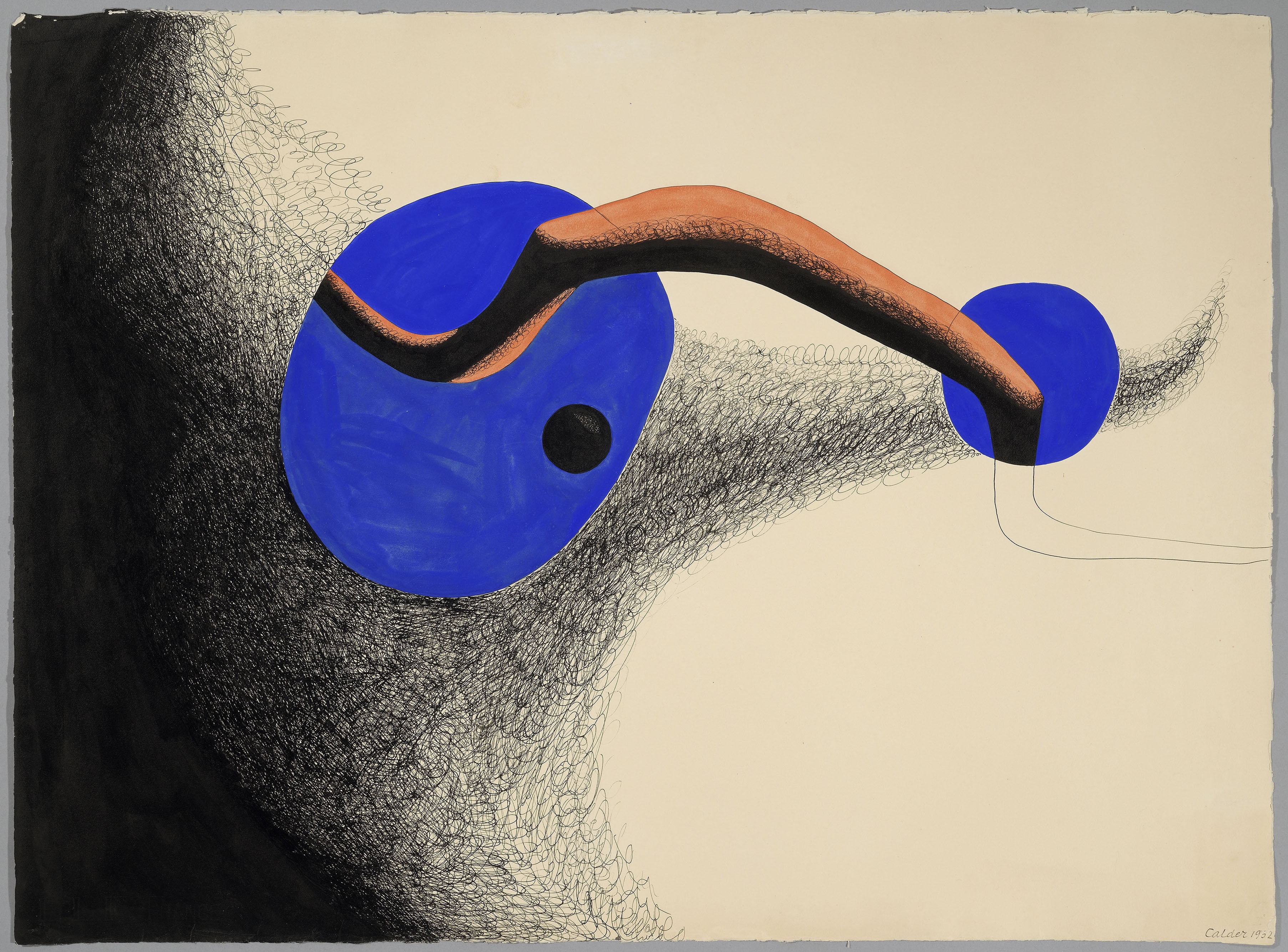

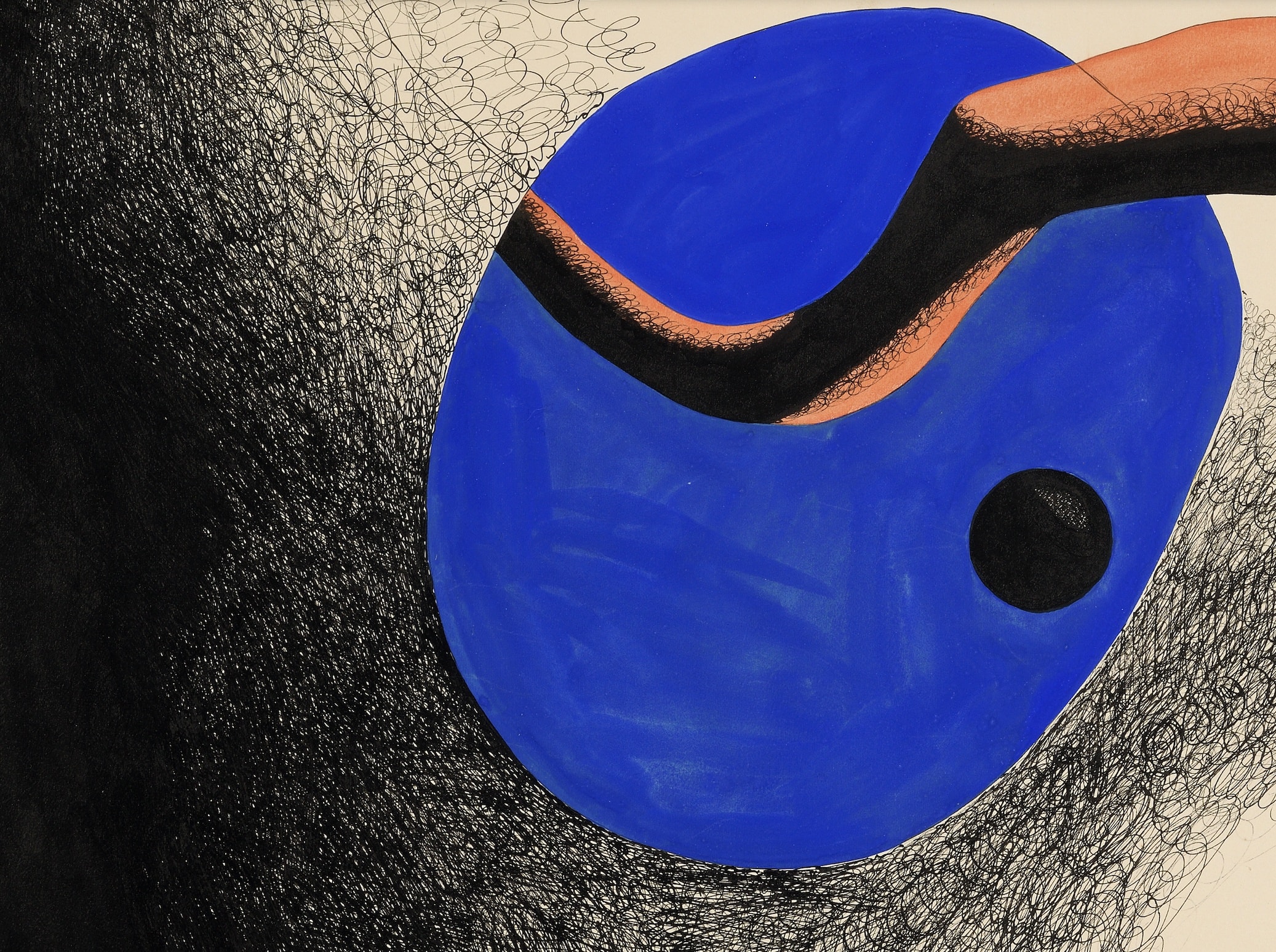

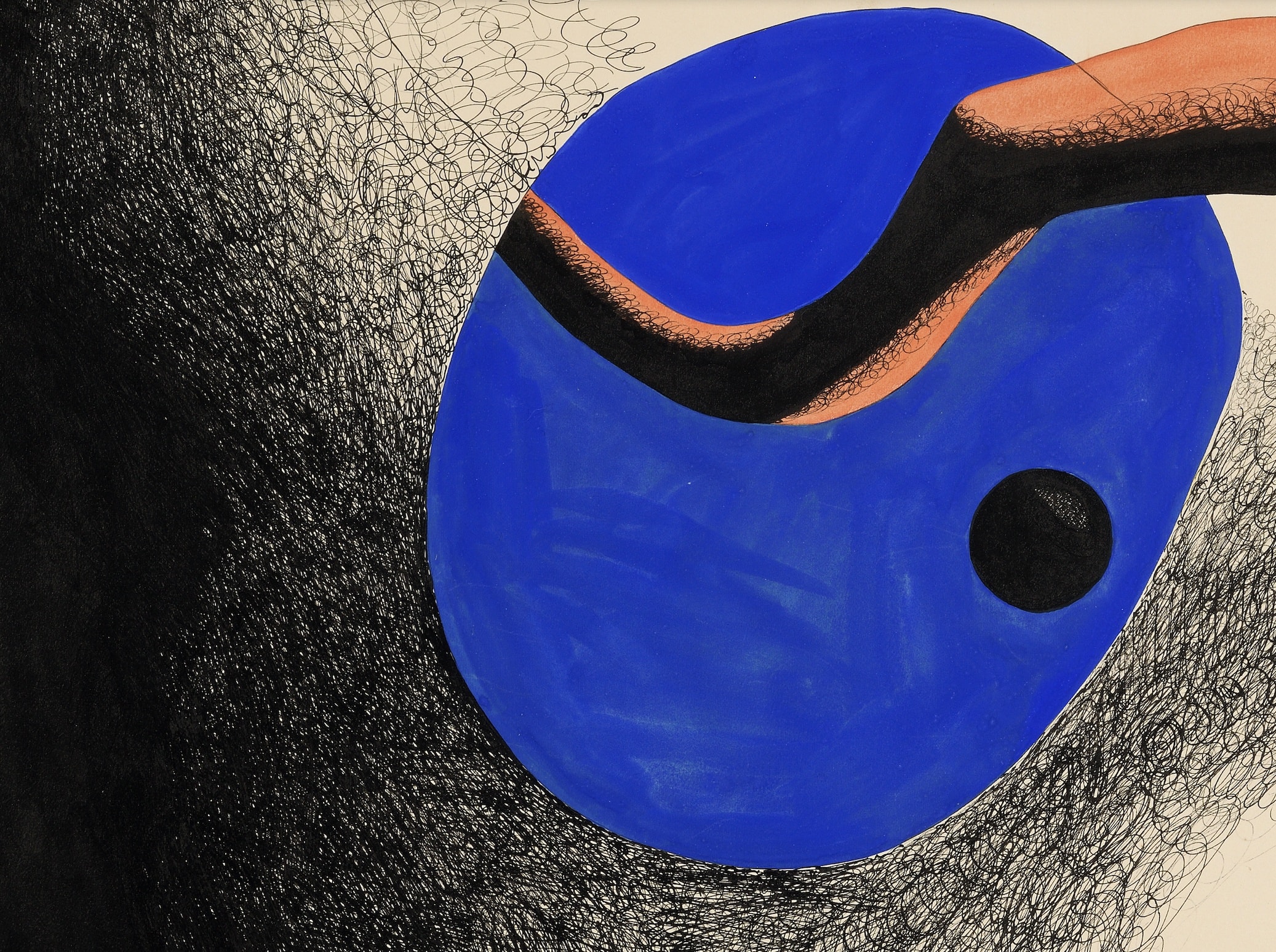

In these works on paper, he adopted the same saturated tone of red and blue which he used in his sculptures. Rather than collapse space into a series of flat planes, as Mondrian did, Calder combined these areas of vivid colour with a cosmic landscape of swirling lines made with pen and ink. These rare experiments made at the frontier of Parisian modernism show Calder’s close connection with continental European art of the 1930s. What is more, as the art historian George Heard Hamilton noted, he was ‘the first American of the twentieth century to win and hold a European reputation.’ It was partly these works on paper which helped him do it.

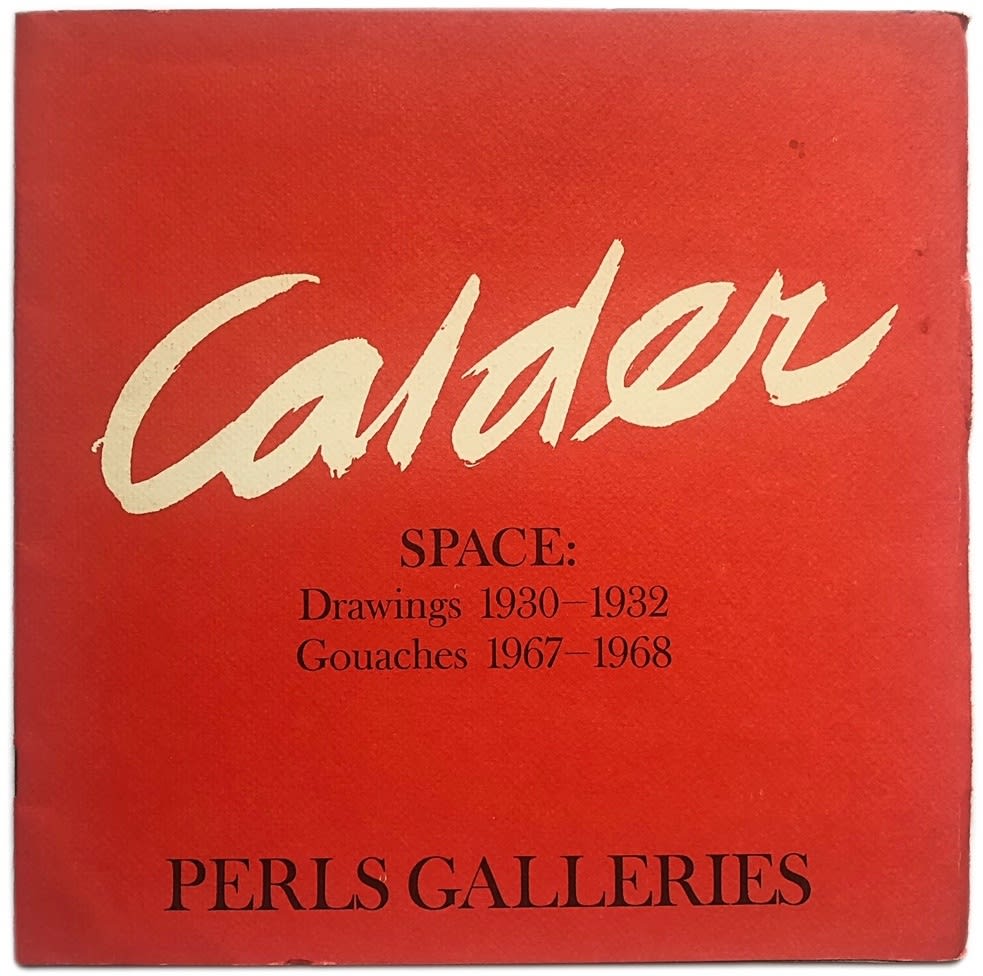

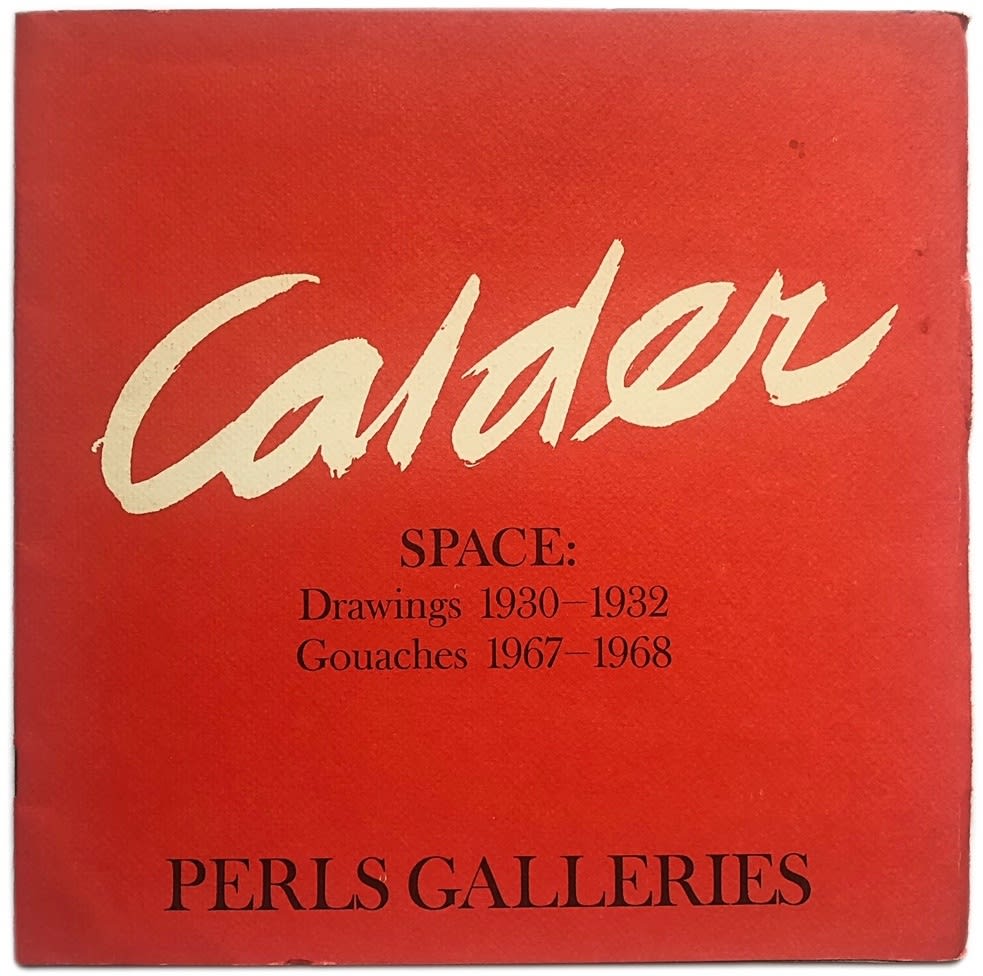

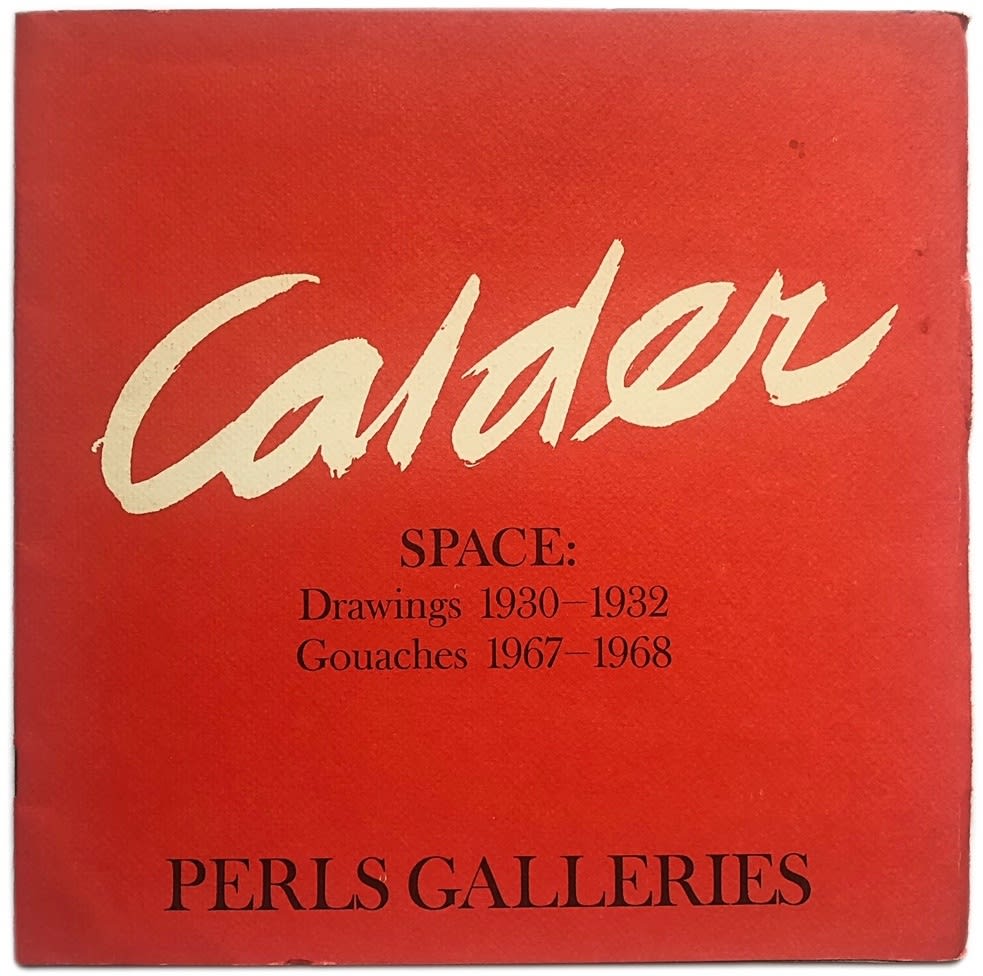

After Calder moved back to the States, settling in Connecticut, these exciting Parisian inventions were largely forgotten. It was not until 1967 that they were put on public view in New York by his dealer Klaus Perls. The exhibition was called Alexander Calder: Early Work - Rediscovered, and it evidently proved successful as a further display of Calder’s Parisian work from the 1930s was held the following year. The subtitle of the 1968 exhibition – ‘Space’ – was typical of modernist art-speak, but its subtext was the febrile race to put a man on the moon.

Stanley Kubrick’s film epic, 2001: A Space Odyssey, was released in May that year, and Apollo 7 – the first manned space flight of the Apollo programme – was launched from Cape Kennedy just a few days before the opening of the ‘Space’ show. Calder himself had a long-standing interest in the cosmos. Sometime in 1919, as a jobbing merchant marine before he became an artist, he found himself on the deck of a ship near Guatemala in Central America. As he recalled later, ‘I saw the beginning of a fiery red sunrise on one side and the moon looking like a silver coin on the other... It left me with a lasting sensation of the solar system.’ Though these planetary influences later came to be mediated by Calder’s sophisticated artistic schema, his work of the early 1930s are less formulaic and register those influences more clearly than any time afterwards.

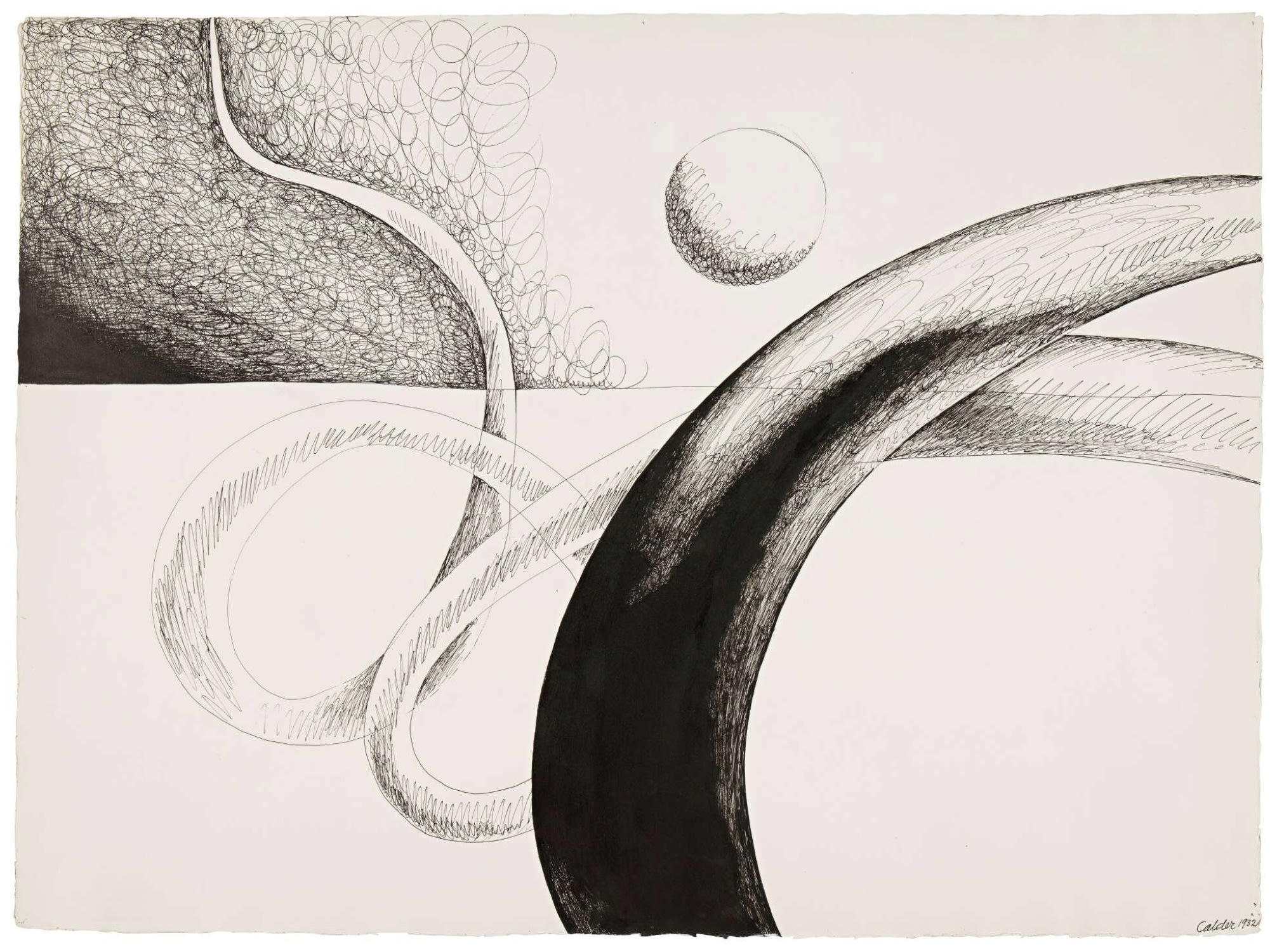

The untitled work by Calder illustrated at the top of this email was not included in either of his two ‘retrospective’ exhibitions at Perls Galleries. Shortly after it was made in 1932, it was acquired by Eric Grate – a Swedish artist, the exponent of a comparable post-Cubist manner, who was also working in Paris in the early 1930s. Other works from the early 1930s included in the two Perls shows are less developed and less colourful, such as Serpentine (illustrated below). It was these works which were perhaps harder for Calder to sell in Paris at the outset of his career, and which he kept with him until they eventually found favour in the space-crazed New York of the 1960s. The early sale of this untitled work to Grate might be taken as a mark of its quality. In any case, its strength of colour and originality of composition ensure its lasting appeal – far beyond the Paris of the ‘30s and the New York of the ‘60s.

IMAGES

1. Alexander Calder, Untitled, 1932, gouache and india ink, 58 x 78 cm

2. Charles Karsten, Mondrian in his Paris studio, 1933

3. Louisa James, who Calder married in January 1931

4. Untitled (detail)

5. Perls Galleries exhibition catalogue of Alexander Calder: Space, held between 15 October and 9 November 1968

6. A poster for 2001: A Space Odyssey, released in May 1968

7. Alexander Calder, Serpentine, 1932, Private Collection © Calder Foundation, New York

June 16, 2020

![]() Instagram

Instagram ![]() Join the mailing list

Join the mailing list