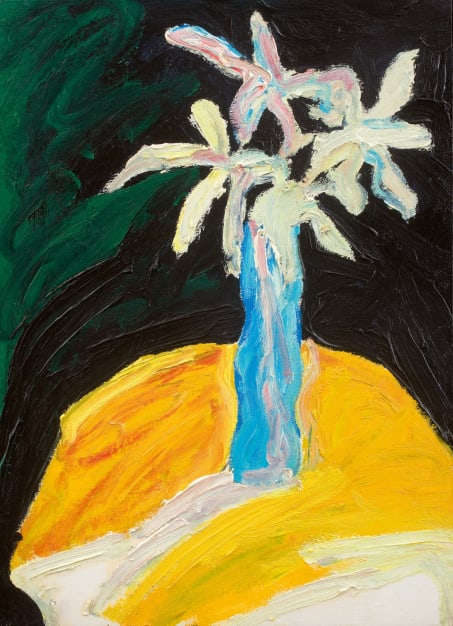

To coincide with Piano Nobile’s new exhibition William Crozier: Seize the Flow’r, InSight considers a significant group of still life paintings made by Crozier upon his return from New York in 1979.

William Crozier

Still Life, 1979-80

Writing in 1790, Robert Burns gave a dazzling account of the ‘drunken blellum’ Tam o’ Shanter. A drinker and a chancer, Burns’s famous poem sees Tam cantering through thunderstorms and beguiled by a ‘vauntie’ witch. While his adventure unfolds, Tam’s ‘sulky, sullen dame’ sits at home awaiting his return. Beneath the poem’s bawdy, humour and fantasy, however, lies a solid bedrock of sober morality. So much is apparent from the famous lines:

But pleasures are like poppies spread,

You seize the flow’r, its bloom is shed.

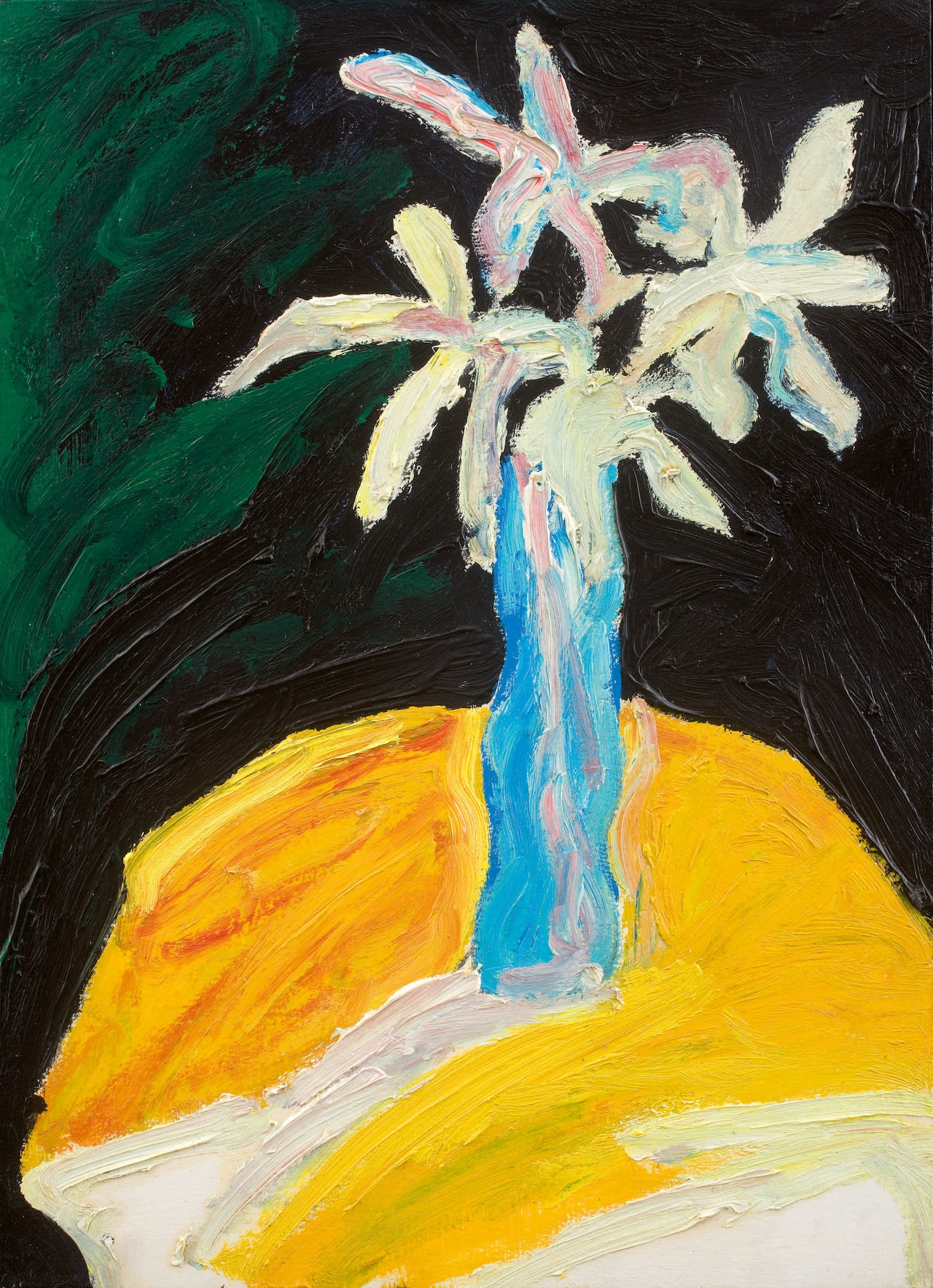

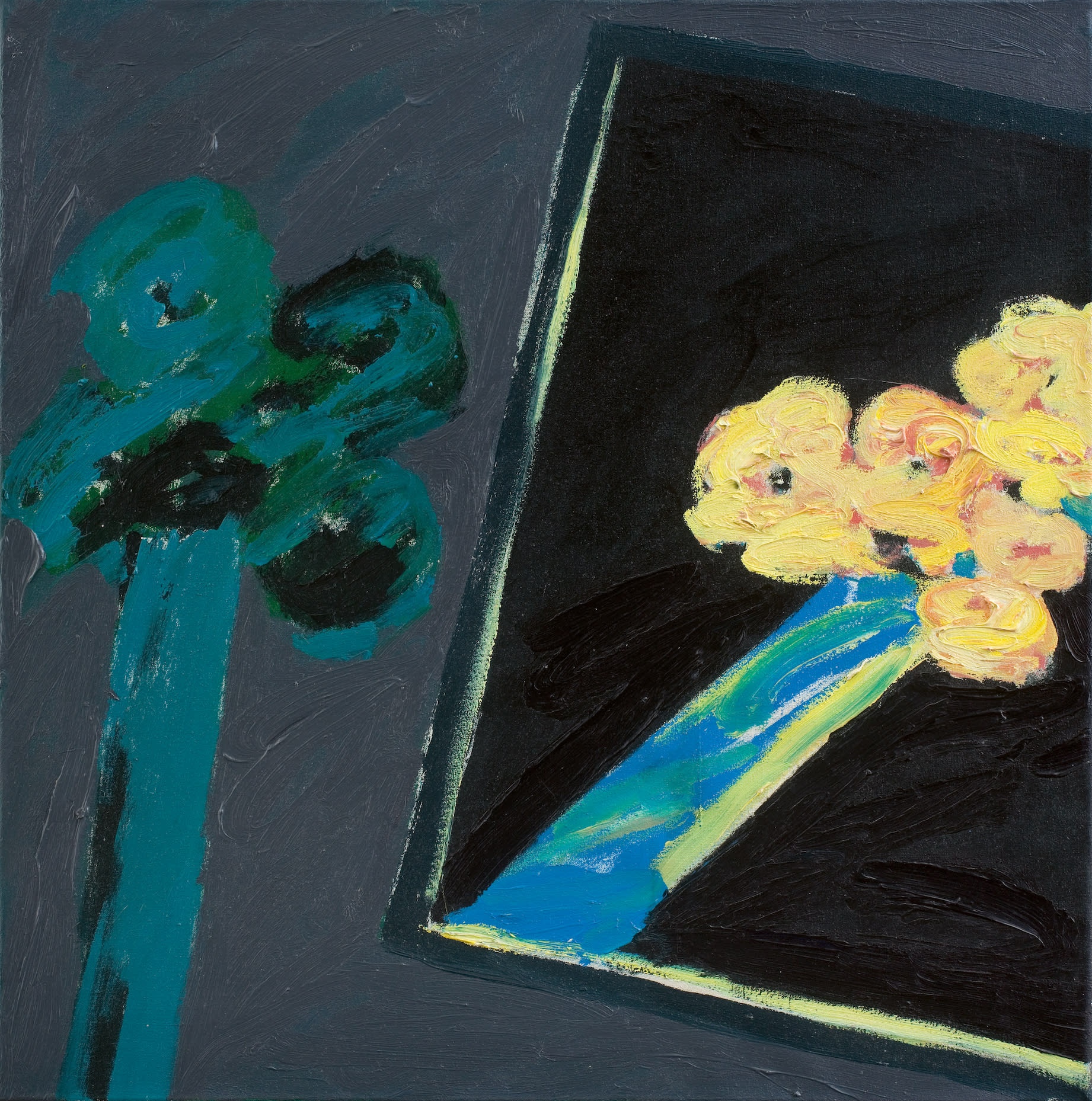

These words were often in William Crozier’s (1930–2011) thoughts when making his prodigious cycle of still life paintings in 1979 and 1980. Avoiding the clichéd visual language of skulls and bubbles, Crozier’s work was nevertheless animated by the same profound notions of vanitas found in Burns’s poetry. A range of artistic devices make Crozier’s paintings at once visually distinctive and thematically loaded. Dramatic lighting, flickering shadows, non-naturalistic colour and doppelgänger mirror images give these works a unique intensity.

In the summer of 1979 Crozier paid his first visit to New York as a visiting professor at New York Studio School. The visit had a stirring effect, causing him to reflect upon his European identity and the importance of a long tradition in Western painting. Upon his return in September, he began concertedly to paint vases of flowers. He wrote at the time,

I found that New York detonated in me an upsurge of passion for my own cultural roots. I looked again at European painting with a clarity and excitement I had not felt in this raw form since I was a student. I felt that my cultural inheritance was so great that I could squander it.

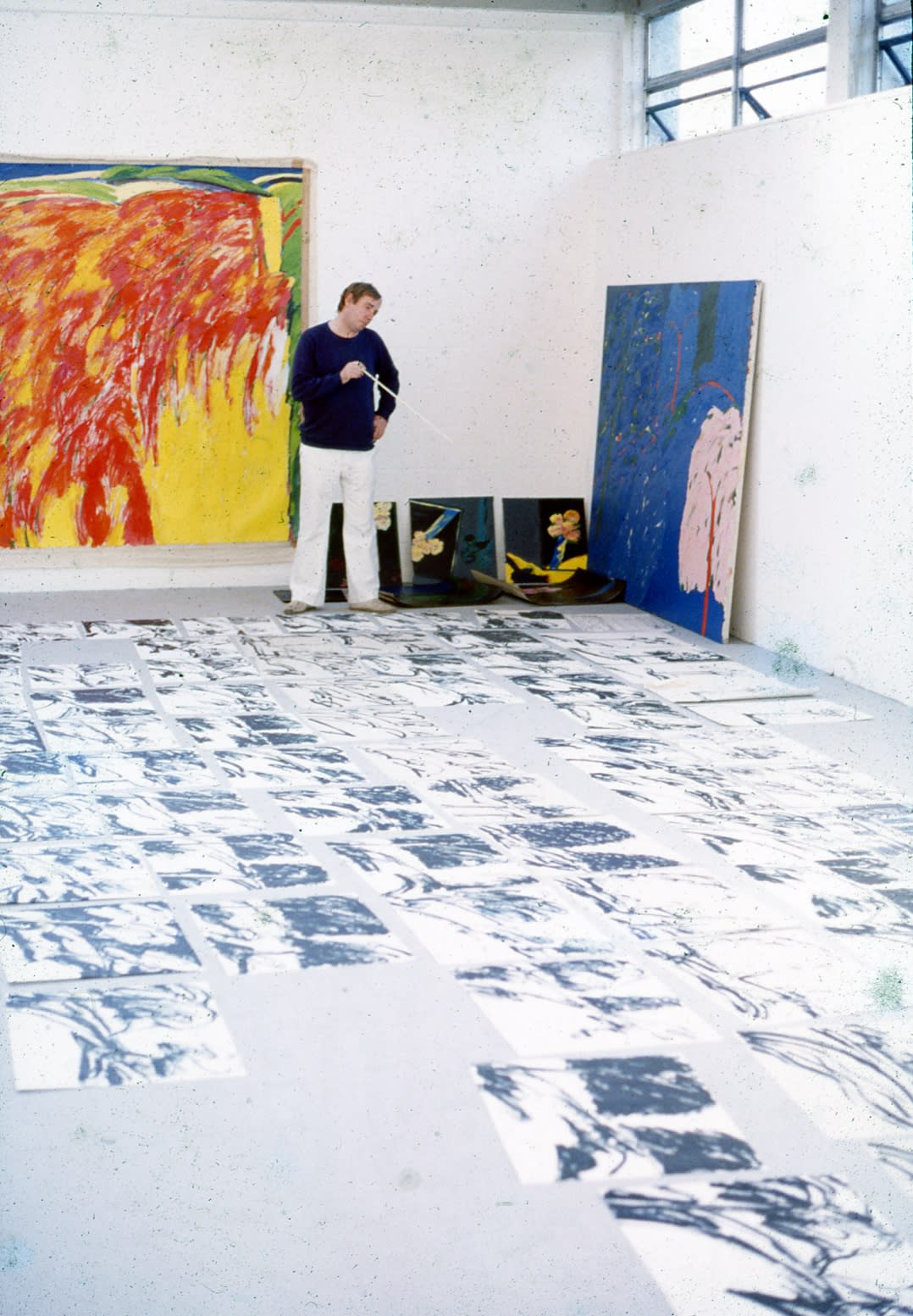

This upsurge of passion had a tangible effect on Crozier’s output. Within ten months of his return from New York, he had made enough work from which to select 160 paintings for exhibition at Swiss Cottage Library. (In the photograph above, he can be seen in his Winchester studio choosing which works to show.) The exhibition took place in August 1980 and included a variety of subjects. As well as large-scale oil paintings depicting streetscapes of New York and North London there was an array of still life painting in oils, watercolours and acrylic. A few years later in 1984 these still life paintings were again the focus of an exhibition, this time at Galleria del Cavallino in Venice. Since that time, however, they have only rarely been seen in public. Piano Nobile’s current exhibition brings them together again for the first time in nearly forty years.

Many artists and art historians have long felt that art develops sequentially; one thing leads to another. An unbroken chain binds Caravaggio’s fruit basket to Miró’s lemon and Picasso’s leeks. Crozier shared this outlook and regarded his own work as a contribution to the combined legacy of Western still life art. He admired Chardin and Fantin-Latour alike, and he held the Spanish painter Juan Sánchez Cótan in special regard, remarking that ‘he filled my garden with cardoons’. The accomplishment of Crozier’s own paintings stems not simply from his own original artistic devices, but also from the giants upon whose shoulders he painted.

Images:

1. William Crozier, Still Life, 1980, oil on hardboard, 50.8 x 36.8 cm

2. An illustration of Tam o' Shanter by Robert Burns, circa 1790-1800, British Museum

3. William Crozier, Still Life, 1980, oil on canvas, 51 x 51 cm

4. William Crozier in his Winchester studio, July 1980, photographed by Katharine Crouan

5. An installation shot of William Crozier: Seize the Flow'r

6. Juan Sánchez Cótan, Still Life with Game, Vegetables and Fruit, 1602, Museo del Prado